Bookends to this last week:

On Monday 5 March 2018 the draft revised NPPF , accompanying consultation proposals document and the Government’s response to the housing white paper consultation were all published, as well as the two documents I’ll focus on in this blog post:

– Supporting housing delivery through developer contributions: Reforming developer contributions to affordable housing and infrastructure (which also addresses proposed reform to CIL); and

– Draft Planning Practice Guidance for Viability

On Friday 9 March 2018 Draft Planning Practice Guidance: Draft updates to planning guidance which will form part of the Government’s online Planning Practice Guidance was published.

The draft revised NPPF itself says very little on developer contributions, CIL and viability.

On contributions, paragraph 34 of the draft (headed, in contrast to the “developer contributions” document, “development contributions” – consistency of terminology would be good!) states:

“Plans should set out the contributions expected in association with particular sites and types of development. This should include setting out the levels and types of affordable housing provision required, along with other infrastructure (such as that needed for education, health, transport, green and digital infrastructure). Such policies should not make development unviable, and should be supported by evidence to demonstrate this. Plans should also set out any circumstances in which further viability assessment may be required in determining individual applications.”

On viability:

“58. Where proposals for development accord with all the relevant policies in an up-to- date development plan, no viability assessment should be required to accompany the application. Where a viability assessment is needed, it should reflect the recommended approach in national planning guidance, including standardised inputs, and should be made publicly available.”

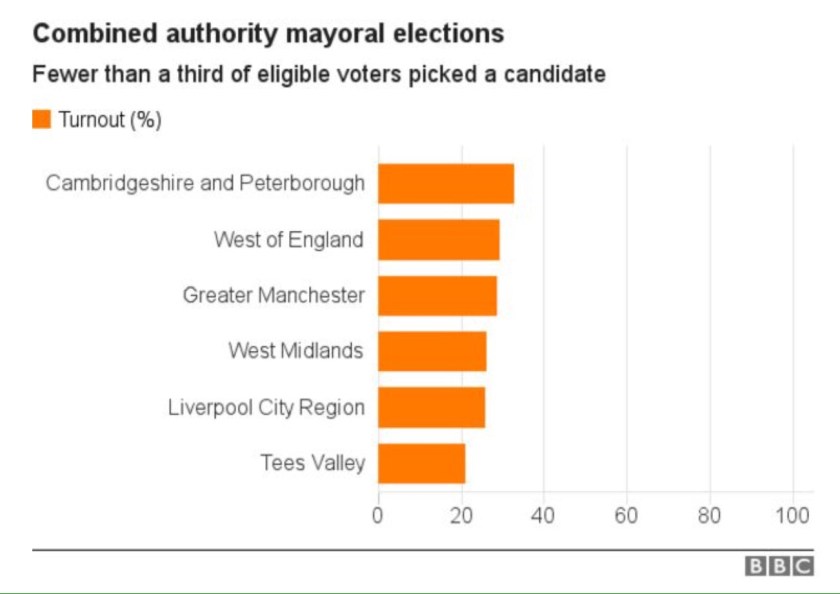

The Developer Contributions consultation document (responses sought by 10 May) addresses both contributions by way of section 106 planning obligations and by way of CIL. The document is accompanied by a research report commissioned from the University of Liverpool, The Incidence, Value and Delivery of Planning Obligations and Community Infrastructure Levy in England in 2016-17 which has some interesting statistics, underlining for me the scale of monies already being secured from development, over £6bn in 2016/2017:

It is clear from the consultation document that we are still on a journey to an unknown destination:

“The reforms set out in this document could provide a springboard for going further, and the Government will continue to explore options to create a clearer and more robust developer contribution system that really delivers for prospective homeowners and communities accommodating new development.

One option could be for developer contributions [towards affordable housing as well as infrastructure] to be set nationally and made non negotiable. We recognise that we will need to engage and consult more widely on any new developer contribution system and provide appropriate transitions. This would allow developers to take account of reforms and reflect the contributions as they secure sites for development.

The proposals in this consultation are an important first step in this conversation and towards ensuring that developers are clear about their commitments, local authorities are empowered to hold them to account and communities feel confident that their needs will be met.”

First step in a conversation??

Contributions via section 106 planning obligations

The document sets out perceived disadvantages of relying on section 106 planning obligations, including:

– delays (but there is no mention of how these could easily be reduced by prescriptive use of template drafts and more robust guidance and the Government’s previous proposal for an adjudication process to resolve logjams in negotiations has been dropped)

– the frequency of renegotiations, most frequently changing the type or amount of affordable housing (but with no analysis of why this is so – often in my experience for wholly necessary reasons, often linked to scheme changes or reflection of changed government affordable housing priorities or funding arrangements)

– a concern that they may “only have captured a small proportion of the increase in value” that has occurred over the time period covered by the University of Liverpool research report (but, aside from where the scale of contributions has been depressed from a policy compliant position due to lack of viability, why is this relevant? Planning obligations should be about necessary mitigation of the impacts from development, not about capture of uplifts in land value ).

– lack of transparency.

– lack of support for cross boundary planning.

Despite these criticisms, the document does not propose significant changes to the section 106 process (or provide any timescale for the further review it alludes to) save for proposing to remove the pooling restriction (Regulation 123 of the CIL Regulations 2010) in areas:

* “that have adopted CIL;

* where authorities fall under a threshold based on the tenth percentile of

average new build house prices, meaning CIL cannot feasibly charged;

* or where development is planned on several strategic sites”

The Government is consulting on what approach should be taken to strategic sites for this purpose, the two options being stated as:

“a) remove the pooling restriction in a limited number of authorities, and across the whole authority area, when a set percentage of homes, set out in a plan, are being delivered through a limited number of large strategic sites. For example, where a plan is reliant on ten sites or fewer to deliver 50% or more of their homes;

b) amend the restriction across England but only for large strategic sites (identified in plans) so that all planning obligations from a strategic site count as one planning obligation. It may be necessary to define large strategic sites in legislation.”

I would prefer to see the pooling restriction dropped across the board. If authorities choose not to adopt a CIL charging schedule but to rely on section 106 planning obligations to make contributions towards infrastructure then why not let them, subject to the usual Regulation 122 test? I thought we wanted a simpler system?

There are sensible proposals for summaries of section 106 agreements to be provided in standard form (although we do not yet have the template), so that information as to planning obligations can be more easily made available to the public, collated and monitored.

Contributions via CIL

The Government’s thinking on CIL continues along the lines set out alongside the Autumn 2017 budget and summarised in my 24 November 2017 blog post CIL: Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For ie wandering dangerously away from the CIL review panel’s ideas of a simpler, more uniform but lower charge regime. The proposed ability for authorities to set different CIL rates based on the existing use of land is inevitably going to make an overly complex system even worse, introducing another uncertainty, namely how the existing use of the land is to be categorised. The Government recognises that risk:

“Some complex sites for development may have multiple existing uses. This could create significant additional complexity in assessing how different CIL rates should be apportioned within a site, if a charging authority has chosen to set rates based on the existing use of land.

In these circumstances, the Government proposes to simplify the charging of CIL on complex sites, by:

* encouraging the use of specific rates for large strategic sites (i.e. with a single rate set for the entire site)

* charging on the basis of the majority use where 80% of the site is in a single existing use, or where the site is particularly small; and

* other complex sites could be charged at a generic rate, set without reference to the existing use of the land, or have charges apportioned between the different existing uses.”

One wonders how this would play out in practice.

It seems that the requirement for regulation 123 lists (of the infrastructure projects or types of infrastructure which the authority intends to fund via CIL – and which therefore cannot be secured via section 106) is to be removed, which is of concern since regulation 123 lists (the use of which should be tightened rather than loosened) serve at least some degree of protection for developers from being double-charged.

The Government is proposing to address one of the most draconian aspects of the CIL process – the current absolute requirement for a commencement notice to be served ahead of commencement of development, if exemptions and the right to make phased payments (where allowed by the authority) are not to be lost, is to be replaced by a two months’ grace period. However, this does not avoid all current problems as any exemptions would still need to be secured prior to commencement.

A specific problem as to the application of abatement provisions to pre-CIL phased planning permissions is to be fixed. These flaws in the legislation continue to emerge, a function of the complexity and artificiality of the whole edifice, which the panel’s proposals would significantly have reduced. In the meantime, we are some way away from actual improvements to the system we are all grappling with day by day, with no firm timescale for the next set of amending Regulations.

Viability

The thrust of the draft planning practice guidance for viability is understood and reflects what had been heralded in the September 2017 Planning for the right homes in the right places consultation document – focus viability consideration at allocation stage, standardise, make more transparent – but there are some surprising/interesting passages:

– Is the Government contemplating review mechanisms that don’t just ratchet upwards? Good if so:

“It is important that local authorities are sufficiently flexible to prevent planned development being stalled in the context of significant changes in costs and values that occur after a plan is adopted. Including policies in plans that set out when and how review mechanisms may be included in section 106 agreements will help to provide more certainty through economic cycles.

For all development where review mechanisms are appropriate they can be used to amend developer contributions to help to account for significant changes in costs and values over the lifetime of a development. Review mechanisms can be used to re- apportion or change the timing of contributions towards different items of infrastructure and affordable housing. This can help to deliver sites that would otherwise stall as a result of significant changes in costs and values of the lifetime of a development.”

– Review mechanisms are appropriate for “large or multi phased development” in contrast to the ten homes threshold in draft London Plan policy H6 (which threshold is surely too low).

– The document advises that in arriving at a benchmark land value, the EUV+ approach (ie existing use value plus premium) should be used. The London Mayor will have been pleased to see that but will then have choked on his cornflakes when the Government’s definition of EUV+ is set out. According to the Government, EUV is not only “the value of the land in its existing use” (reflecting the GLA approach) but also “the right to implement any development for which there are extant planning consents, including realistic deemed consents, but without regard to other possible uses that require planning consent, technical consent or unrealistic permitted development” (which is more like the GLA’s approach to Alternative Use Value!).

Then when it comes to assessing the premium, market comparables are introduced:

“When undertaking any viability assessment, an appropriate minimum premium to the landowner can be established by looking at data from comparable sites of the same site type that have recently been granted planning consent in accordance with relevant policies. The EUV of those comparable sites should then be established.

The price paid for those comparable sites should then be established, having regard to outliers in market transactions, the quality of land, expectations of local landowners and different site scales. This evidence of the price paid on top of existing use value should then be used to inform a judgement on an appropriate minimum premium to the landowner.”

I am struggling to interpret the document as tightening the methodologies that are currently followed, or indeed introducing any material standardisation of approach.

The EUV+ position is covered in more detail by George Venning in an excellent blog post.

– There is a gesture towards standardisation in the indication that for “the purpose of plan making an assumption of 20% of Gross Development Value (GDV) may be considered a suitable return to developers in order to establish viability of the plan policies. A lower figure of 6% of GDV may be more appropriate in consideration of delivery of affordable housing in circumstances where this guarantees an end sale at a known value and reduces the risk.” However, there is no certainty: “Alternative figures may be appropriate for different development types e.g. build to rent. Plan makers may choose to apply alternative figures where there is evidence to support this according to the type, scale and risk profile of planned development.”

More fundamentally, I am sceptical that viability-testing allocations at plan-making stage is going to deliver. At that stage the work is inevitably broad-brush, based on typologies rather than site specific factors, often without the detailed input at that stage of a development team such that values and costs can be properly interrogated and without an understanding of any public sector funding that may be available. If the approach did actually deliver, significantly reducing policy requirements, so much the better, but that isn’t going to happen without viability arguments swamping the current, already swamped, local plan examination process.

Indeed, as was always going to be the case with the understandable drive towards greater transparency, the process is becoming increasingly theoretical (think retail impact assessment) and further away from developers opening their books to demonstrate what the commercial tipping point for them is in reality, given business models, funding arrangements, actual projected costs (save for land), and actual projected values. “Information used in viability assessment is not usually specific to that developer and thereby need not contain commercially sensitive data“.

The document contains more wishful thinking:

“A range of other sector led guidance on viability is widely available which practitioners may wish to refer to.”

Excellent. Such as?

Topically, this week, on 6 and 7 March, Holgate J heard Parkhurst Road Limited’s challenge to the Parkhurst Road decision letter that I referred to in my 24 June 2017 blog post Viability & Affordable Housing: Update. The challenge turns on the inspector’s conclusions on viability. Judgment is reserved.

We also should watch out for Holgate J’s hearing on 1 and 2 May of McCarthy and Stone & others v Mayor of London, the judicial review you will recall that various retirement living companies have brought of the Mayor of London’s affordable housing and viability SPG.

The great thing about about writing a planning law blog is that the well never runs dry, that’s for sure. (Nothing else is).

Simon Ricketts, 10 March 2018

Personal views, et cetera