A is for…

There was an interesting planning appeal decision letter last week concerning a section 106B appeal against refusal of an application made under section 106A to amend a section 106 agreement on the basis that it no longer served a “useful purpose” (the statutory test in section 106A).

This post will look briefly at that decision but first I thought some legislative archaeology might assist.

Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 is of course the statutory successor of section 52 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1971. Under section 52, the commitments had no specific description but were treated effectively as covenants analogous to restrictive covenants given by a landowner to a neighbouring landowner but (unlike usual property law covenants) able to contain positive requirements enforceable against successors in title rather than just restrictions – and, as is the case under section 106, enforceable by the local planning authority.

The only statutory method for amending or removing commitments given within a section 52 agreement was to make an application to what was then the Lands Tribunal (now the Upper Tribunal (Lands Chamber)) under section 84 of the Law of Property Act 1925. In order for such an application to succeed, the Tribunal has to be satisfied (in summary – there are other tests which are less relevant for the purposes of this post) “that by reason of changes in the character of the property or the neighbourhood or other circumstances of the case which the Upper Tribunal may deem material, the restriction ought to be deemed obsolete”.

The section 84 process is slow, uncertain, outside the usual planning system and so on. When section 106 of the 1990 Act came into force on 24 August 1990 the only statutory process remained section 84 of the 1925 Act.

Then in the first of so many waves of amendments to the 1990 Act, along came the Planning and Compensation Act 1991, which came into force on 25 September 1991. The 1991 Act replaced section 106 with, basically, what we have now. Those commitments given by landowners on behalf of themselves and successors were the first time called “planning obligations”.

In those changes, the scope of what could be secured was expanded. Compare the original formulation of what could be secured via section 106 with what it became:

Original:

“(1) )A local planning authority may enter into an agreement with any person interested in land in their area for the purpose of restricting or regulating the development or use of the land, either permanently or during such period as may be prescribed by the agreement.

(2) Any such agreement may contain such incidental and consequential provisions (including financial ones) as appear to the local planning authority to be necessary or expedient for the purposes of the agreement.”

What it became:

“(1) Any person interested in land in the area of a local planning authority may, by agreement or otherwise, enter into an obligation (referred to … as “ a planning obligation ”), enforceable to the extent mentioned in subsection (3)—

- restricting the development or use of the land in any specified way;

- requiring specified operations or activities to be carried out in, on, under or over the land;

- requiring the land to be used in any specified way; or

- requiring a sum or sums to be paid to the authority (or, in a case where section 2E applies, to the Greater London Authority) on a specified date or dates or periodically.”

[When we think about how the use of section 106 planning obligations to secure financial contributions has exploded over the last 30 or so years, it is worth comparing what is now section 106 (1) (d) above with what it replaced: section 106 (2) above. Was this intended at the time? An open question…]

Note also the reference to “by agreement or otherwise” in the first line of the changed version of section 106 (1). This opened up the possibility of the landowner entering into planning obligations by unilateral undertaking rather than just by agreement.

Alongside the reformulation of section 106 was the introduction of section 106A and B (from 10 December 1992), providing a procedure to applying to “modify or discharge” planning obligations in place of using the Law of Property Act 1925 procedure. As I know you know, section 106A allows an application to be made once at least five years have passed since the obligation was entered into – with an available appeal route (although it is worth noting that the Secretary of State can prescribe – very easily in legislative terms, simply a ministerial direction would surely suffice – a period shorter or longer than five years). An application may be made before five years have passed, but in those circumstances there is no right of appeal. If an application is made, the local planning authority has to determine either:

- that the planning obligation shall continue to have effect without modification;

- if the obligation no longer serves a useful purpose, that it shall be discharged; or

- if the obligation continues to serve a useful purpose, but would serve that purpose equally well if it had effect subject to the modifications specified in the application, that it shall have effect subject to those modifications.

Section 106B provides for appeals to be made to the Secretary of State. (Interestingly, sub-section 106 (5) requires that before determining the appeal “the Secretary of State shall, if either the applicant or the authority so wish, give each of them an opportunity of appearing before and being heard by a person appointed by the Secretary of State for the purpose”. I interpret that as the parties having a right for any appeal to be determined bother than by written representations, i.e. by a hearing or inquiry).

What is meant by “no longer serves a useful purpose”? What did Parliament intend to connote by the use of those words? Was this just intended as a modernisation and abbreviation of the test in section 84 of the Law of Property Act 1925? Should this be treated as a “useful planning purpose” or will any useful purpose do? Those words “No longer”: What if the obligation never served a useful purpose? And why five years? Of course, given the lack of any other statutory route to amend section 106 agreements and unilateral undertakings, all of this has come under increasing scrutiny both by inspectors on appeals and by the courts.

I have been looking back today at Hansard reports of debates in parliament that led to the Planning and Compensation Act 1990 to see whether legislators gave any of this specific thought. It would have been good if they had done but I can’t see that they did.

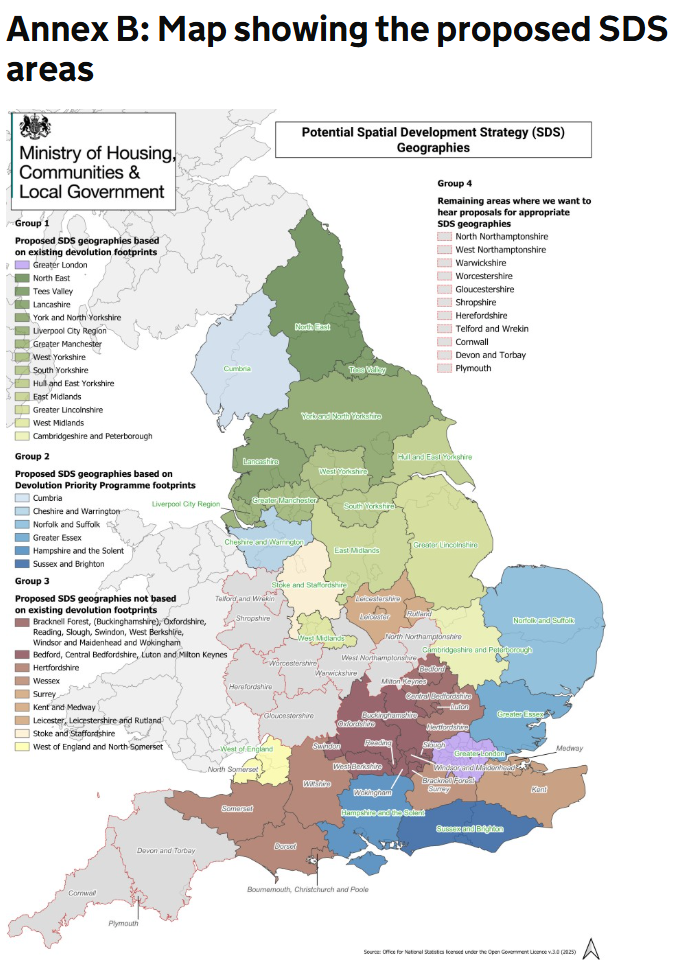

All this is particularly topical at the moment, at a time where many schemes are stalled through lack of viability and where development may be able to progress if planning obligations previously entered into are modified or discharged to the extent necessary to achieve viability. The government of course (a) missed any opportunity during the course of the Planning and Infrastructure Act 2025 to reintroduce the section 106BA and BC procedure that we had between April 2013 and April 2016 to allow developers to apply to modify or discharge affordable housing obligations in Section 106 agreements where those obligations made a development economically unviable and (b) is still not exactly welcoming section 73 applications with open arms that serve as a vehicle to achieve that outcome (see Matthew Pennycook’s 18 December 2025 letter to the Planning Inspectorate) so, if the local planning authority is not willing to engage in such a renegotiation of its own volition, section 106A and B are the only game in town.

Which now takes me to that recent appeal decision I mentioned. This is a decision letter dated 20 January 2026 dismissing appeals by Hodson Developments and Chilmington Green Developments against the non-determination by Ashford Borough Council and Kent County Council of applications made under section 106A to make a total of 122 modifications to a section 106 agreement dated 27 February 2017 in connection with planning permission which had been granted for a large development including 5,750 homes together with commercial and other uses. Central to the inspector’s decision was the question as to whether the viability or otherwise of the scheme and the effect of an obligation and other obligations on viability, is relevant to whether an obligation serves a useful purpose.

The appeals have a long history, which I suspect is far from concluded. The position is not wholly clear but it seems that an initial application to modify or discharge various obligations was submitted in 2022 before the expiry of five years when the local planning authority at that time would have had a broad discretion as to whether to agree to the application (given that an appeal would not lie under section 106B in relation to such an application). After an initial judicial review that was settled, the applicant commenced a second set of judicial review proceedings, alleging that Ashford Borough Council and Kent County Council were wrong to conclude that viability of the development was not a relevant consideration under section 106A and that in any event in their consideration of the issue they erred in law. Following a renewal hearing in March 2022, the claim was held by Lieven J to be unarguable. On the specific point as to whether viability is a material consideration, she “remain[ed] unconvinced that it is not a material consideration”. However she considered that the councils had properly taken it into account. “I am not going to consider whether or not viability was legally a material consideration because that is a somewhat complicated point of law and would involve considering a number of previous cases. It is sufficient for the purposes of ground 1 that the local authorities in this case did consider viability with some care and detail…”

There was then a further application, presumably by which time the five years had expired, which was the subject of the appeals considered by the inspector (two appeal references – one for obligations in the agreement enforceable by Ashford Borough Council, the other for obligations enforceable by Kent County Council). Some of the requests for modifications were withdrawn but there was still a long list.

After an eight day inquiry the inspector (solicitor Grahame Kean) disagreed that the effect of an obligation and other obligations on viability, may be relevant to whether an obligation serves a useful purpose (see paragraph 33). He goes on:

“34. An obligation must itself be soundly based on established criteria, ie it must be necessary to make a development acceptable in planning terms, directly related to the development, and fairly and reasonably related in scale and kind to the development. If, say an obligation fails these criteria but requires some act unconnected to or at odds with the development, the obligation would be liable to be struck down as invalid. However, in a s106A application the question is different from the legitimacy of the obligation itself. As counsel for the Appellant accepted, the obligation must have been entered into for a planning purpose in the first place.10 It would be rare for the useful purpose not to be a planning one but as noted, the question under s106A is whether the obligation serves any useful purpose, not just a useful planning purpose.

35. The Appellant’s counsel claims that “in the present case, frustrating the development goes to the planning purpose”. Counsel might not have intended to refer to a deliberate attempt to frustrate a development as much as an objectively assessed outcome due to acts or omissions of local planning authorities. At any rate there is no evidence of any deliberate attempt to frustrate the development and if there were, s106A would not be the appropriate way to deal that scenario.

36. Furthermore, if a planning obligation is duly completed, although it may have the effect of “frustrating” the development in the sense that it prevents progress in the eyes of a developer unless and until certain acts are performed, and although ultimately circumstances may obtain such that it is no longer regarded (by some at least) as a viable project, that seems to me a consequence, and not part of the original purpose or reason for exacting the obligation in the first place.

37. The existence of an obligation, in the context of a development scheme, is to make development acceptable in planning terms. That is its quintessential purpose. The statutory criteria are simple and do not refer to the viability of the development. The obligations have a contractual nature, albeit statutorily based, which it is in the interests of the parties to be able to enforce, the one against the other, and subject only to limited exceptions set out in s106 that allow discharge or modification. Since they are limited exceptions that derogate from the principle of contractual enforceability, it also seems arguable that exceptions should be strictly applied.

38. An obligation can have a useful purpose of preventing development or further development until performed. This may make it inherently impossible, for financially viability reasons, to carry out or complete a development, but that does not necessarily deny the usefulness of the purpose in preventing a development that would otherwise be unacceptable in planning terms. Circumstances may throw light on whether the purpose continues to be “useful” but viability issues would not transcend the basic question of whether the obligation continues to meet any useful purpose.”

Faced with such a spread of requested modifications (including, in relation to affordable housing, requested modifications as to tenure requirements and delivery triggers), the inspector considered that the “evidence is not so clear and unambiguous as to persuade me that unless the obligations in the s106 Agreement were discharged or modified all as requested, the scheme would in fact be rendered financially unviable and unable to proceed.”

This may all be justified on the particular facts, I don’t know. However, standing back, if the inspector’s approach is that an obligation relating to, say, the provision of a particular percentage of affordable housing, still serves a useful purpose if the evidence were to show that unless that percentage is reduced (or for instance the tenure mix altered or the trigger delayed) the development will not proceed, and that with the modification there is every prospect of the development proceeding, resulting in actual provision of affordable housing (albeit a lower percentage than was initially promised), is this approach correct? And if so, where is there any common sense in it – where really is the “useful purpose”? – and what can be done? In a situation like this, rather than defer progress on development indefinitely, is the developer really to go back to the very beginning, to prepare and submit a fresh application for planning permission, delaying any delivery for many years and at frankly massive cost? The lack of any proportionate mechanism to reflect current economic circumstances, with any necessary protections, would be surely a scandal?

Simon Ricketts, 25 January 2026

Personal views, et cetera