Today’s Commons Housing Communities and Local Government Committee’s report Delivering 1.5 million new homes: Land Value Capture (28 October 2025) contains recommendations which are more wide-ranging than the report’s title would suggest: some practical and, one would hope, uncontroversial; others touching on some raw political nerves at MHCLG no doubt.

Starting with the latter, do turn to the “epilogue” which comments directly on what were at that stage just media reports as to the “package of support for housebuilding in the capital” announcement which the government and the Mayor of London issued on 23 October 2025. The Committee expresses itself to be “seriously concerned by media reports that London’s affordable housing target could be cut” and “the Secretary of State may be considering suspending local authorities’ powers to charge the Community Infrastructure Levy to address concerns about development viability. None of the evidence to our inquiry—including from representatives of developers—advocated abolishing CIL entirely as a means of addressing viability concerns. On the contrary, we heard that the Government should reform CIL to extend its coverage where it is viable.”

“The Ministry must continue its work with the Greater London Authority to deliver an acceleration package, so that London boroughs are delivering housing in line with their local housing need targets. In response to this Report, the Ministry must provide its assessment of how changes to London’s affordable housing target may deliver more affordable housing units, by increasing the number of new homes built overall. Any reduction to London’s affordable housing target must be accompanied by a clawback mechanism to ensure developers return a portion of their profits to the local authority, ringfenced for affordable housing delivery, if a development surpasses an agreed benchmark profit. If London’s affordable housing target is reduced and the number of affordable housing units delivered declines, the Ministry and the Greater London Authority must commit to reinstating the 35% target.”

Perhaps this epilogue is slightly premature, given the actual announcement proved only to be a prologue to a consultation process that will run “from November” (late November is my guess). Perhaps the Committee should hear further evidence on that back of the consultation material to be published – it is slightly odd to be responding just to a newspaper report, particularly given that the actual announcement has been made.

But that epilogue does point to the fundamental policy tension in the current economic environment: what matters most – affordable housing delivery by percentage, or by absolute numbers? See for instance its recommendation that the government’s “forthcoming reforms to its guidance on viability assessments must ensure developers reliably deliver on their agreed affordable housing commitments, with viability assessments only used to alter these commitments retrospectively in the most exceptional circumstances. To support this, we recommend that all local authorities in England must be encouraged to set a minimum percentage target for affordable housing in their local plan [NB what don’t?], with a ‘fast-track’ route planning route for developments which meet this local target.”

“Too often, site-specific viability assessments are used by developers to negotiate down affordable housing requirements in circumstances where this is completely unjustifiable. Affordable housing contributions are frequently the first provision to be cut following a viability assessment, even where a developer may be making other significant contributions through Section 106 agreements and CIL. In areas with high land values, viability assessments should only be used in this way in very exceptional circumstances. Currently, not all local authorities have their affordable housing requirements clearly set out in local policy. Greater clarity from local authorities would provide developers with the right incentives to avoid lengthy viability negotiations, and ensure more applications are meeting local affordable housing requirements from the outset.

As part of its ongoing review of the viability planning practice guidance, the Government must consider how different types of developer contribution could be re-negotiated following a viability assessment, to protect affordable housing contributions. The Government must also update national policy to encourage all local authorities to set a minimum percentage target for affordable housing in their Local Plan for all major developments that include housing. This figure should be based on a local need assessment for affordable housing in each local authority, with particular regard for the local need for Social Rent homes. Local authorities should be encouraged to offer a ‘fast-track route’ for developments which meet the local affordable housing target, by making those developments exempt from detailed viability assessments and re-assessments later in the development process. This would encourage developments with a high percentage of affordable housing and speed up the delivery of housing of all tenures.

The Government must continue to develop its proposal to publish indicative benchmark land values to inform viability assessments on Green Belt land across England. The Government must publish different benchmark land values for each region of England, to reflect variation in land values. The Government must also ensure that the viability planning practice guidance contains clear advice on the “local material considerations” that would warrant local adjustments. The Government should continually review the effectiveness of the policy and consider how it may be extended to development on land that is not in the Green Belt.”

On land value capture itself:

“There is scope to reform the current system of developer contributions in England to capture a greater proportion of land value uplifts from development to deliver affordable housing and public infrastructure. There is a compelling case for such reforms—especially in the context of a deepening housing crisis and with public finances currently under strain. However, a radical departure from the Section 106/Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) regime, which currently constitute the existing mechanisms of land value capture in England, would risk a detrimental impact on the supply of land in the short-term. We recognise that this would be disruptive to the Government’s housebuilding agenda.

Reforms to land value capture should be iterative, starting with improvements to existing mechanisms. Therefore, the Government must immediately pursue the reforms to Section 106 and CIL outlined in the chapters below. These reforms must optimise the system’s capacity to capture land value uplifts and deliver infrastructure and affordable housing—particularly homes for Social Rent—in line with the Government’s wider policy ambitions. The Government must also trial additional mechanisms of land value capture in areas where there are significant uplifts in land value which current mechanisms may not capture effectively. Specifically, the New Towns programme discussed in Chapter 5 presents a vital opportunity to test new ways of financing infrastructure delivery on large developments and learn lessons for future reforms.

Any reforms to land value capture should also be considerate of the wider tax system, to balance public needs and equitable charges on development. To support this work, the Government should publish updated land value estimates, which were last published in August 2020. If the Government does not intend to do so, it must explain why it no longer publishes this data.”

In essence, the Committee sees any radical change as likely to be disruptive to the government’s current agenda. Instead, it is recommending a number of changes which in my view are “no brainers”, for instance better resources for local planning authorities and looking to simplify the approach to section 106 agreements and to CIL:

Reforms to section 106 agreements

“There is a strong case for the introduction of template clauses for aspects of Section 106 agreements across England, as was recommended by the National Audit Office and others. Templates would allow local authorities to focus negotiations on site-specific factors rather than legal wordings. Template clauses would also allow for greater standardisation and clarity of requirements across all local authorities, and in turn reduce the workload of local authorities and Small and Medium-sized Enterprise developers.

As part of the site thresholds consultation that will take place later this year, the Ministry must seek views on how standardised Section 106 templates could most effectively streamline the negotiation process across sites of all sizes. Based on the consultation responses, the Ministry must work with the Planning Advisory Service to develop a suite of Section 106 template clauses and publish these within six months of the consultation closing. Alongside their publication, the Ministry must also update its guidance to local authorities on Planning Obligations to encourage local authorities to adopt these template clauses.”

I covered the same ground in my 14 June 2025 blog post Why Does Negotiating Section 106 Agreements Have To Be Such A Drag? Not only that, but my firm has also been working on an actual template draft for small and medium sized schemes and a specific set of proposals for ironing out the pinch points that currently exist at every step of the sway from arriving at heads of terms through to agreement completion. This was there to be grasped – it is a national embarrassment. We held a workshop on 30 September 2025, attended by a selection of thirty or so lawyers and planners from the public and private sectors, developers and representatives of industry bodies with MHCLG present in an observer capacity. If you weren’t invited I apologise but we were limited by the size of our meeting room! The draft output from the workshop will be released next month. If there is an organisation out there which is willing to make a larger space available in late November for a launch event please let me know.

Section 106 dispute resolution scheme

This may be why I write blog posts…. The Committee picked up on a reference I made in the blog post mentioned above to section 158 of the Housing and Planning Act 2016 which has never been switched on, allowing for a dispute resolution procedure to be able to be invoked where necessary during the course of negotiations.

“Local planning authorities across England have expressed concern that protracted Section 106 negotiations are causing delays to housing delivery. Drawn out negotiations do not benefit public outcomes and cause undue delays to development, which may impede the Government’s housebuilding ambitions. Whilst we recognise the Minister for Housing and Planning’s concerns that introducing a dispute resolution scheme may add complexity to the system, we believe the potential benefits to affordable housing delivery and unlocking stalled development outweigh this risk.

The Government should introduce a statutory Section 106 dispute resolution scheme, under the provisions of the Housing and Planning Act 2016. If the Government does not intend to pursue this, it should set out a detailed explanation as to why the Ministry has chosen not to implement the provision legislated for by Parliament in the 2016 Act. This should include setting out any specific technical or legal barriers to implementation which the Ministry has identified.”

Community Infrastructure Levy

Again, nothing earth-shattering. Rather, calls for more transparency as to which authorities are charging CIL and at what rates; widening opportunities for authorities to pool receipts (and recognising the opportunity that the reintroduction of strategic planning will bring) and greater focus on infrastructure funding statements.

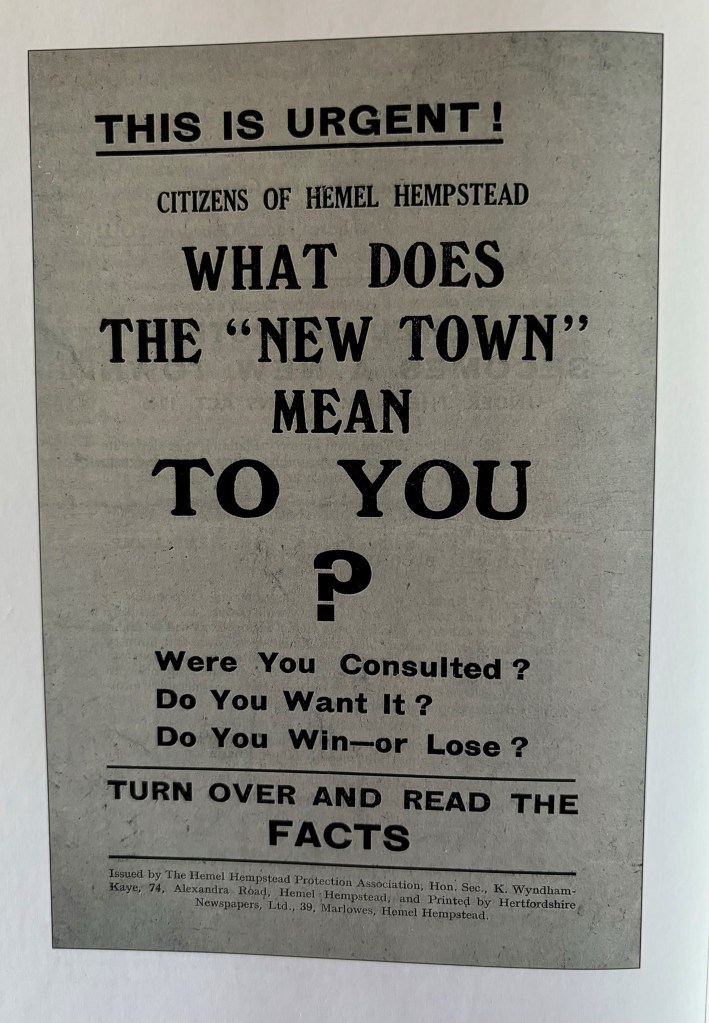

On new towns:

The Committee calls on the government to set out where the funding is to come from (“The Government’s New Towns programme is likely to require billions of pounds of public and private investment over several decades, including millions from HM Treasury to establish development corporations during this Parliament”); greater use should be enabled of tax increment funding to fund infrastructure in cities and new towns. Specifically on the role that land value capture might play:

“There is significant potential to use land value capture as part of funding the proposed New Towns, especially on green field sites. However, we are concerned that the Government has announced substantial detail of the 12 potential sites without a planning policy to protect land value, contrary to the recommendation of the New Towns Taskforce. It appears that the Government has not yet established any delivery body to purchase land or enter agreements with landowners, which risks allowing developers considerable time to acquire sites for speculative development and immediately push up land values. The Taskforce said that, in the worst-case scenario, this could “jeopardise New Town plans”.

The Government must immediately conduct an analysis of Existing Use Values (EUV) on each of the 12 sites to maximise the capture of future land value uplifts, and develop plans for using appropriate mechanisms for land value capture on each site. This must include the option of development corporations using Compulsory Purchase Orders to assemble land where ownership is fragmented or negotiations stall. The Government must ensure arrangements for the purchase of land on New Towns sites are in place before it announces its final decision on locations by spring 2026.”

“The Ministry is right to prioritise New Towns which have the greatest potential to boost housing supply in the short-term, but its plan to “get spades in the ground on at least three new towns in this Parliament” does not match the scale of the Government’s housebuilding ambition. The New Towns programme can and must make a contribution towards increasing housing supply during this Parliament.

The Government must immediately clarify how housing delivery in New Towns will interact with local authority housing need targets. In its final response in spring 2026, the Government must include a roadmap for the New Towns programme, to show when each development corporation will be established, when development will commence on each site, and the estimated development timeline for each New Town.”

So will the government meet its 1.5m homes target?

“The housing sector is eagerly awaiting the Government’s Long-Term Housing Strategy, which it first announced in July 2024. Originally, this was to be published alongside the Spending Review in spring 2025. The continuing lack of a cohesive plan to deliver 1.5 million new homes has left the sector in the dark. We are also deeply disappointed that the Government has been unwilling to engage with us on the development of the Strategy, or provide any updates on its delayed publication, other than to tell us that it will be published “later this year”.”

“The Government can only begin to make significant progress towards its 1.5 million target once the sum of local housing need targets in Local Plans add up to that figure. Whilst the Government’s reforms to the National Planning Policy Framework seek to plan for approximately 370,000 new homes per year, local authorities will take several years to transition to this national annual target, as the currently Local Plans take seven years to produce and adopt on average. The Government has stated its ambition to introduce a 30-month plan-making timeline, but the relevant provisions in the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act 2023 to speed up plan-making have still not been implemented.

The Government must immediately bring forward its Long-Term Housing Strategy without further delay. It must set out an ambitious, comprehensive, and achievable set of policies that will deliver 1.5 million new homes by July 2029. The Strategy must prioritise implementing reforms to the plan-making system to move towards a 30-month timeline. The Strategy document must include an annex to provide the Ministry’s assessment of how many net additional dwellings each policy change will contribute towards annual housing supply, adding up to 1.5 million new homes over the five-year Parliament. If the Ministry is unable to supply this, the Government must make an oral statement to the House to confirm how many new homes it will deliver by the end this Parliament.”

There we have it. If nothing else, that will all spur us on with the work on the template section 106 agreements work and, related to that, I’m very keen to discuss how section 158 of the Housing and Planning Act 2016 might provide an effective, light touch, procedure.

Simon Ricketts, 28 October 2025

Personal views, et cetera