Topical issue: what are the legal constraints on the Government and local authorities in setting the fee rates and cost recovery regimes for administrative and court processes?

Claimant and applicant fee rates in particular are seen by the Government as a lever to seek to

– ensure that users of procedures make a fair contribution to the costs of providing them

– reduce the burden on the public purse and

– winnow out those who are seen as misusing the system.

This is however a dangerous game, if access to justice is to be maintained in accordance with domestic and international legal principles. How to get it right?

Dove J heard on 19 July the judicial review by RSPB, Friends of the Earth and ClientEarth of the Government’s changes to the cost capping regime regime that applies to JRs relating to environmental law matters. They take the position that the changes breach the Aarhus Convention’s requirement that access to environmental justice must be available, without prohibitive cost. I have previously blogged on the Government’s changes. ClientEarth issued this press release after the hearing but judgment has been reserved.

I would not be surprised if that set of proceedings did not end up in the Supreme Court. If so, it could be a worthy sequel to two interesting rulings from the Supreme Court in the last couple of weeks in relation to different subject areas but that same underlying theme.

R (Unison) v Lord Chancellor (Supreme Court, 26 July 2017) concerned a challenge by trade union Unison to the Employment Tribunals and the Employment Appeal Tribunal Fees Order 2013. The Supreme Court agreed with the claimant that the fee regime for claimants in employment tribunal proceedings and appellants in relation to appeals to the Employment Appeal Tribunal was unlawful because of its effects on access to justice. The full judgment handed down by Lord Reed and supplementary judgment by Lady Hale in relation to discrimination issues are well worth reading. Here are some quotes, which you may care to read with our planning system in mind:

There is a “constitutional right of access to justice: that is to say, access to the courts (and tribunals: R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex p Saleem [2001] 1 WLR 443).” (paragraph 65)

“At the heart of the concept of the rule of law is the idea that society is governed by law. Parliament exists primarily in order to make laws for society in this country. Democratic procedures exist primarily in order to ensure that the Parliament which makes those laws includes Members of Parliament who are chosen by the people of this country and are accountable to them. Courts exist in order to ensure that the laws made by Parliament, and the common law created by the courts themselves, are applied and enforced. That role includes ensuring that the executive branch of government carries out its functions in accordance with the law. In order for the courts to perform that role, people must in principle have unimpeded access to them. Without such access, laws are liable to become a dead letter, the work done by Parliament may be rendered nugatory, and the democratic election of Members of Parliament may become a meaningless charade. That is why the courts do not merely provide a public service like any other.” (paragraph 68)

“People and businesses need to know, on the one hand, that they will be able to enforce their rights if they have to do so, and, on the other hand, that if they fail to meet their obligations, there is likely to be a remedy against them. It is that knowledge which underpins everyday economic and social relations.” (paragraph 71)

“There is however no dispute that the purposes which underlay the making of the Fees Order are legitimate. Fees paid by litigants can, in principle, reasonably be considered to be a justifiable way of making resources available for the justice system and so securing access to justice. Measures that deter the bringing of frivolous and vexatious cases can also increase the efficiency of the justice system and overall access to justice.” (paragraph 86)

“The Lord Chancellor cannot, however, lawfully impose whatever fees he chooses in order to achieve those purposes. It follows from the authorities cited that the Fees Order will be ultra vires if there is a real risk that persons will effectively be prevented from having access to justice. That will be so because section 42 of the 2007 Act contains no words authorising the prevention of access to the relevant tribunals. That is indeed accepted by the Lord Chancellor. ” (paragraph 87)

“In order for the fees to be lawful, they have to be set at a level that everyone can afford, taking into account the availability of full or partial remission. The evidence now before the court, considered realistically and as a whole, leads to the conclusion that that requirement is not met. In the first place, as the Review Report concludes, “it is clear that there has been a sharp, substantial and sustained fall in the volume of case receipts as a result of the introduction of fees”. While the Review Report fairly states that there is no conclusive evidence that the fees have prevented people from bringing claims, the court does not require conclusive evidence: as the Hillingdon case indicates, it is sufficient in this context if a real risk is demonstrated. The fall in the number of claims has in any event been so sharp, so substantial, and so sustained as to warrant the conclusion that a significant number of people who would otherwise have brought claims have found the fees to be unaffordable.” (paragraph 91)

“The question whether fees effectively prevent access to justice must be decided according to the likely impact of the fees on behaviour in the real world. Fees must therefore be affordable not in a theoretical sense, but in the sense that they can reasonably be afforded. Where households on low to middle incomes can only afford fees by sacrificing the ordinary and reasonable expenditure required to maintain what would generally be regarded as an acceptable standard of living, the fees cannot be regarded as affordable.” (paragraph 93)

“Given the conclusion that the fees imposed by the Fees Order are in practice unaffordable by some people, and that they are so high as in practice to prevent even people who can afford them from pursuing claims for small amounts and non- monetary claims, it follows that the Fees Order imposes limitations on the exercise of EU rights which are disproportionate, and that it is therefore unlawful under EU law.” (paragraph 117)

The previous week the Supreme Court had returned to the difficult and long-running saga of challenges to Westminster City Council’s fees regime for the licensing of sex shops. The case has been an unholy mess for the Council. It had been setting licensing fees at a rate that included its costs of enforcing the licensing scheme against unlicensed third parties running sex shops. The fee was made up of two parts. One part was payable regarding the administration of the application and was non-refundable. Another part (which was considerably larger – £29,435 in 2011/12) was for the management of the licensing regime and was refundable if the application was refused. Licensed shops brought a challenge, arguing that the second element of the fee was in breach of the Provision of Services Regulations 2009 (SI 2009/2999) (which had been made to give effect domestically to EU Directive 2006/123/EC) and that the only fees that the Council could levy related to the administrative costs of processing the relevant applications and monitoring compliance with the terms of the licence by licence holder, rather than fund enforcement against those who didn’t seek or obtain licences.

Regulation 18 of the 2009 Regulations provides that:

“(2) Authorisation procedures and formalities provided for by a competent authority under an authorisation scheme must not –

(a) be dissuasive, or

(b) unduly complicate or delay the provision of the service”

“(4) Any charges provided for by a competent authority which applicants may incur under an authorisation scheme must be reasonable and proportionate to the cost of the procedures and formalities under the scheme and must not exceed the cost of those procedures and formalities.”

The Court of Appeal had upheld the claim in 2013 and as a result made repayments totalling £1,189,466 to the licence holders, together with a further £227,779.15 which it paid, it turned out, by mistake.

However, the Supreme Court overturned that ruling in 2015, finding that the fees regime was basically lawful. There was one aspect which the court referred to the European Court of Justice, namely the way in which the part of the fee which covered wider enforcement costs was paid upfront when the application was made but only repaid if the application was unsuccessful. The European Court confirmed in November 2016 that this aspect of the regime was indeed unlawful.

The case came back to the Supreme Court with the Council arguing that it was entitled to be paid or repaid the sums it repaid to licence holders in 2013 and the licence holders in turn contending that they are entitled to retain the repayment made to them in full, because it was charged in a way which in part at least had been unlawful. In its judgment dated 19 July 2017 the court basically agreed with the Council that it is entitled to be reimbursed to the extent that it has raised fees lawfully, but it has remitted the case to the Administrative Court to resolve a whole host of complexities that arise from the whole mess, including a number of accounting issues, complications arising where licensees have ceased to exist and the recovery of the monies that the Council had paid by mistake.

Implications for planning

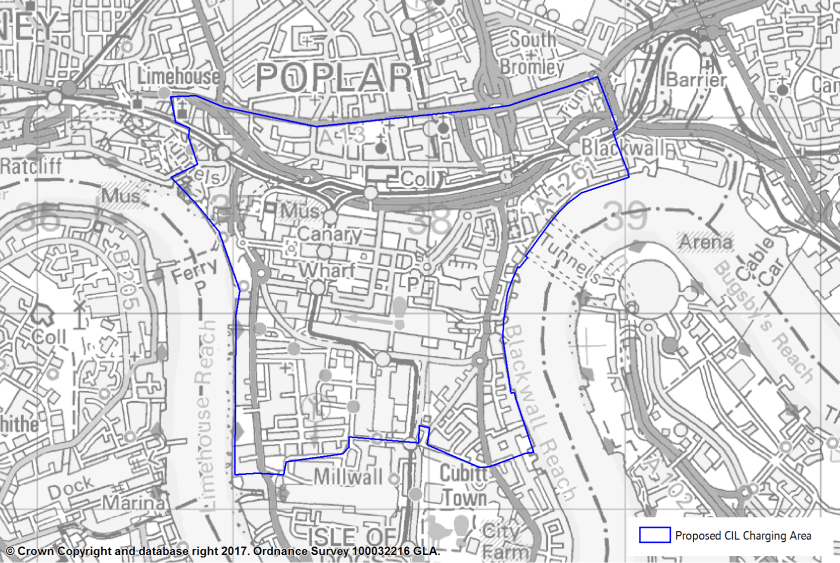

It may be thought that our planning system currently has the opposite problem: many applicants would be willing to pay higher application fees if the fees enabled authorities to staff up and offer a faster, better, service. The Government went less far than many would have wished when it announced in its February 2017 housing white paper that:

“We will increase nationally set planning fees. Local authorities will be able to increase fees by 20% from July 2017 if they commit to invest the additional fee income in their planning department. We are also minded to allow an increase of a further 20% for those authorities who are delivering the homes their communities need and we will consult further on the detail. Alongside we will keep the resourcing of local authority planning departments, and where fees can be charged, under review.” (para 2.15)

But even that relatively weak and overdue measure has not yet been brought into effect.

More controversially the white paper indicated that the Government would consult on introducing a fee for applicants submitting planning appeals: “We are interested in views on this approach and in particular whether it is possible to design a fee in such a way that it does not discourage developers, particularly SMEs, from bringing forward legitimate appeals. One option would be for the fee to be capped, for example at a maximum of £2000 for the most expensive route (full inquiry). All fees could be refunded in certain circumstances, such as when an appeal is successful, and there could be lower fees for less complex cases.”

The white paper consultation sought views on:

“a) how the fee could be designed in such a way that it did not discourage developers, particularly smaller and medium sized firms, from bringing forward legitimate appeals;

b) the level of the fee and whether it could be refunded in certain circumstances, such as when an appeal is successful; and

c) whether there could be lower fees for less complex cases.”

This is another area where we await an indication of whether the new ministerial team will take a different approach. Careful note will need to be taken of the Supreme Court’s rulings in Unison and in Heming.

Finally, court fees continue to increase, most recently, from 26 July 2016, by way of the Civil Proceedings, Family Proceedings and Upper Tribunal Fees (Amendment) Order 2016 . The Order’s explanatory memorandum puts it like this:

“The majority of fees affected by this instrument will be increased by a rate which is above the level of inflation. The Government has decided, in view of the financial circumstances and given the reductions to public spending, that such an increase is necessary in order to make sure that the courts and tribunals are adequately funded and access to justice is protected, in the long term.”

In relation to judicial review, the fee levels are still relatively modest compared to some other court procedures but are still significant sums for some claimants to find, particularly at short notice:

– application for permission to apply £154 (previously £140)

– request to reconsider at a renewal hearing £385 (previously £350)

– to proceed to a full hearing if permission is granted £770, or £385 if reconsideration fee already paid (previously £700 and £350)

There is that tired saying about justice in England being open to all, like the Ritz Hotel. It’s true, save that the Ritz doesn’t close its doors for months on end. The court term ends on Monday 31 July (with the next term starting on 1 October).

The end of this term marks the end of an era for the Supreme Court: Lords Neuberger and Clarke are retiring (there is an amusing Legalcheek account of their 28 July valedictory speeches) and Lady Hale will become president (only of the Supreme Court unfortunately rather than of the western world). If only we were to see more blogging from the retired judiciary such as that of Sir Henry Brooke. Do read his recent blog post on a truly surreal Tribunal case.

Simon Ricketts, 29 July 2017

Personal views, et cetera