For those of us living or working in London, I reckon that Sadiq Khan’s manifesto for his next term as Mayor, published on 19 April 2024, is an important read. But yesterday it was rather drowned out by the media coverage that day of Labour’s press statement on green belt policy reform.

I’ll deal first with Labour’s green belt announcement.

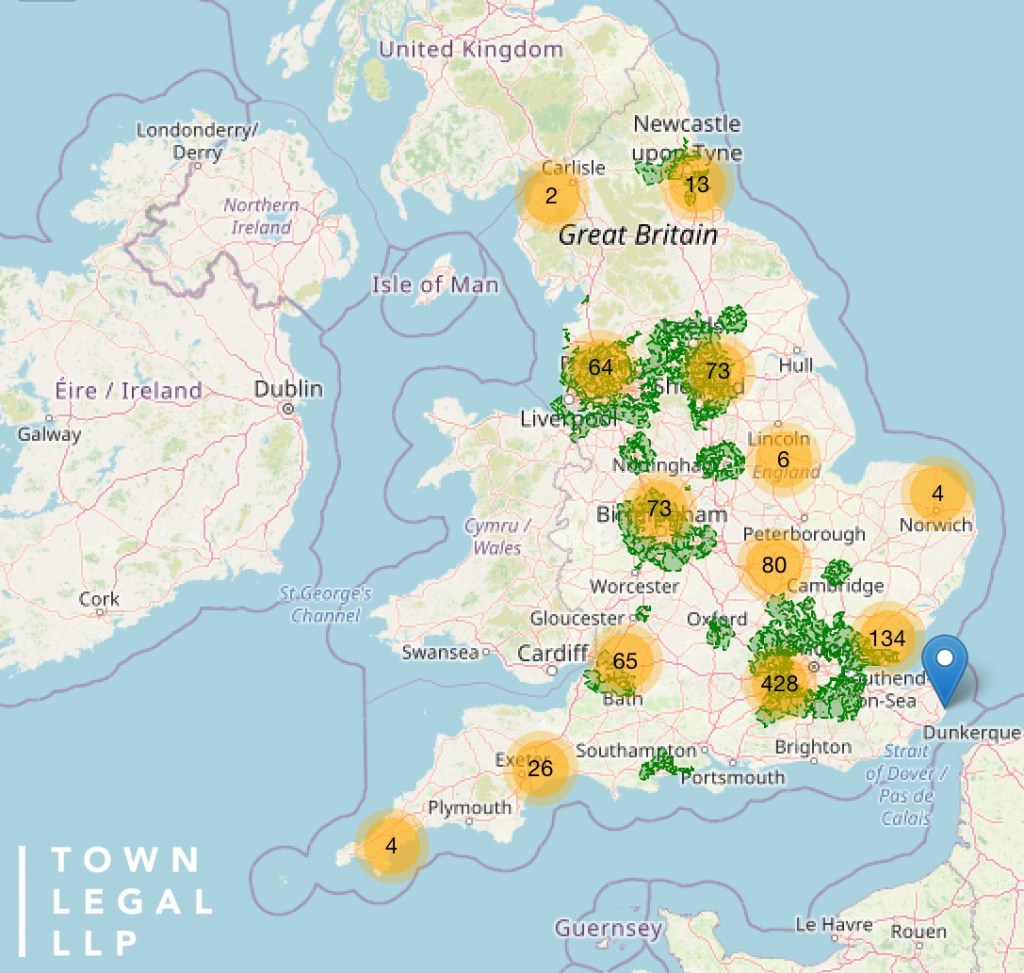

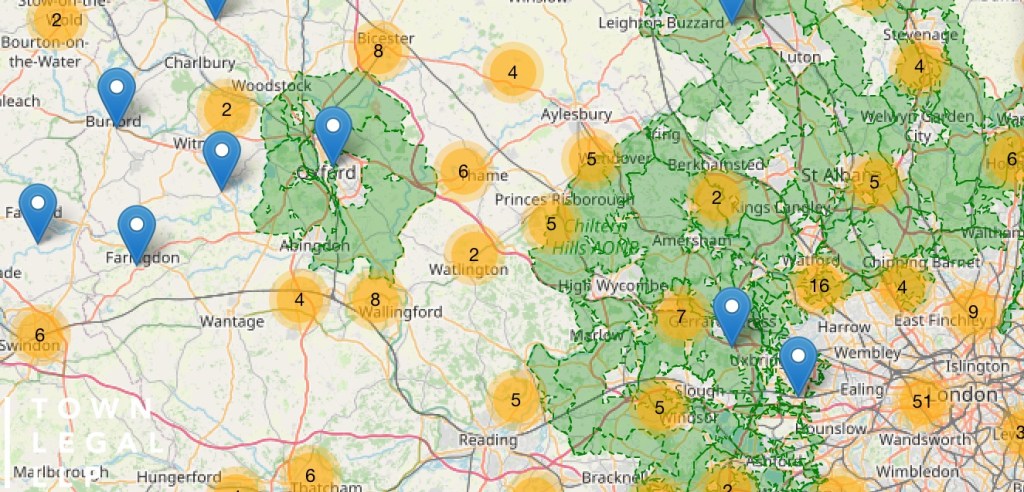

As a country we certainly need to resolve the negative effects of this misunderstood policy concept (Sam Stafford’s updated blog post, The Green Belt. What it is; what it isn’t; and what it should be contains all (more than?) anyone could ever want to know about the subject). And for a sense of the sheer extent of green belt and its obvious consequent throttling effect on the areas it encircles, see for example Town Legal’s planning appeals map – green belt areas marked in … green).

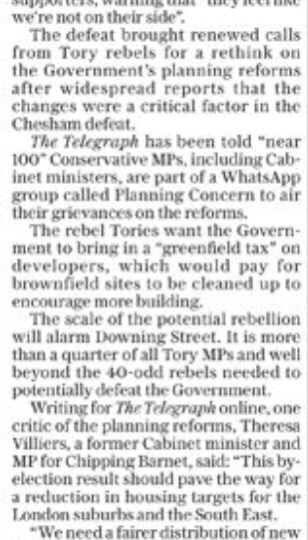

It is surely positive in the context of a continuing, indeed worsening, housing crisis and the lack of other options which are likely to be sufficient and deliverable, that there is talk from Labour of using some green belt land to deliver more new homes. After all, even “going there” is politically brave. But fine words butter no parsnips. And I wonder whether the proposals in some ways just add to the confusion.

These are the core proposals from the press release :

“A Labour government would take a brownfield first approach to development across England, prioritising building on previously developed land in all circumstances and taking steps to improve upon the government’s lacklustre record of brownfield build out rates. Areas with enough brownfield land should not release greenbelt.

A Labour government will implement five ‘golden rules’ for Grey Belt development:

1. Brownfield first – Within the green belt, any brownfield land must be prioritised for development.

2. Grey Belt second – poor-quality and ugly areas of the Green Belt should be clearly prioritised over nature-rich, environmentally valuable land in the green belt. At present, beyond the existing brownfield category the system doesn’t differentiate between them. This category will be distinct to brownfield with a wider definition.

3. Affordable homes – plans must target at least 50% affordable housing delivery when land is released.

4. Boost public services and infrastructure – plans must boost public services and local infrastructure, like more school and nursery places, new health centres and GP appointments.

5. Improve genuine green spaces – Labour rules out building on genuine nature spots and requires plans to include improvements to existing green spaces, making them accessible to the public, with new woodland, parks and playing fields. Plans should meet high environmental standards.”

What can we take from this as to what Labour would actually do, if elected?

This press statement is of course not intended to be picked over by people like me or you. Its purpose is to influence potential voters and to give us all a flavour of we would be likely to see, whilst giving plenty of wriggle-room when it comes to the actual implementation. So I’m not going to carp too much, but…

- Are these tests for plan-makers or for decision-makers? If the former (likely), will there be a transition period before the new policy kicks in for decision-makers, if there is an otherwise up to date local plan?

- So a basic hierarchy of brownfield; non-green belt greenfield; brownfield green belt; grey belt green belt; green belt green belt? It strikes me that this gives too much emphasis on the physical characteristics of the site itself rather than its sustainability and appropriateness in spatial terms? And how is this sequential testing to be carried out? The old questions as per the retail and flood risk sequential tests: to what extent can proposals be disaggregated; what is the area of search; deliverable over what period and what about where (as is often the case) there is not really a choice between site A and site B because the level of unmet need is such that A and B are both needed, and more besides?

- How do references to “poor-quality and ugly” and “nature-rich, environmentally valuable” match up at all to the five traditional purposes for which green belt is designated – (a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas; (b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another; (c) to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment; (d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and (e) to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land. Is that what “poor-quality” means perhaps – not fulfilling those purposes?

- If “brownfield” equates to what is currently defined as previously developed land, and treated less restrictively in green belt policy, give me an example of this untapped resource of non brownfield “grey belt”? And we’ve all gone on endlessly about the subjectivity of the concept of “beautiful” only now to be faced with a policy concept of “ugly“!

- 50% is an eye-catching number for some areas but as a target what will actually change in practice? And define “affordable”. Will the opportunity be to introduce these requirements via national development management policies? That would be some exciting and early mission creep!

- 4 and 5 are nothing new.

- It’s not all about housing folks! What about logistics and other developments which need to be located in the green belt?

Now to Sadiq Khan’s manifesto, “A Fairer, Safer, Greener London” published ahead of the 2 May 2024 election. I’ll just draw out some quotes:

From his ten pledges:

3 Build 40,000 new council homes by the end of the decade

8 More support for renters – delivering new affordable ‘rent control homes’ and empowering Londoners to take on landlords through a New Deal for Renters

9 Continue world-leading action to tackle air pollution and the climate crisis – from making all buses zero-emission to providing air pollution filters to primary schools

10 Deliver a new London Growth Plan, with a target of creating more than 150,000 good jobs by 2028 and increasing living standards for Londoners

Under the heading “Tackling the housing crisis”:

“To unblock more new homes, I will take decisive action where needed to create new Land Assembly Zones and set up more Mayoral Development Corporations to boost overall housing supply and drive regeneration. These will deliver new sustainable communities with homes for first-time buyers as well as homes for social rent. I’ll work with a Labour government to strengthen planning so that the London Plan can go even further in supporting the delivery of the affordable housing our city needs, while unlocking economic growth and being the greenest ever plan for our city.”

Under the heading “Cleaning up London’s air”:

“making London the world’s first electric-vehicle ready global city by working with partners to double the amount of electric vehicle charging points installed since 2016 to more than 40,000 by 2030

continuing to oppose any expansion of airports in London”

Under the heading “Growing our economy”:

“I will build on our city’s economic recovery and set out an exciting new London Growth Plan, developed in close collaboration with councils, businesses and trade unions.

This new growth plan will set out how we can boost jobs and growth in the well-established sectors of our economy, including finance and business services; retail, hospitality, leisure and tourism; manufacturing; logistics; built environment and construction. I will also focus on and champion some of the fastest growing sectors, such as health and life sciences; digital including fintech, retail tech, cyber and AI; creative industries including film, fashion, TV, music and games; climate tech and the energy sector.”

“To help boost economic growth across our city, I will support individual boroughs to build on their strengths – from the new global culture and education powerhouse that is East Bank in Stratford, to the world-leading TV and film production cluster in West London, and the internationally influential cutting edge cancer research centre in Sutton. This also means working with councils and businesses to deliver a new vision and plan for the centre of London, ensuring that we can continue to compete with the central activity zones of other global cities like Paris and New York. London has roared back as a tourist destination since the pandemic and I’ll continue to work with partners to improve our tourism offer.”

“London is home to more than 600 high streets. We learned during the pandemic how intimately connected we are to local high streets, and their importance to our communities. That’s why I want to do more to protect, restore and improve them. If I’m re-elected, I will launch a support fund and set out a new vision for the future of London’s high streets, building on the work we have already done. I’ll also explore planning changes that can help breathe new life into our high streets, helping to ensure they remain a central feature of our economic and civic life.”

Not a word about green belt, you might note…

Simon Ricketts, 20 April 2024

Personal views, et cetera