Article 4 directions are a small but essential cog in the complicated machine that is the English planning system. With the more widespread reliance by Government on permitted development rights, it falls to local planning authorities to make article 4 directions to disapply, where appropriate, those rights in relation to specific types of developments and/or in specific areas.

From 1 August 2021, we are potentially approaching a breakdown in this machine in the face of the proposed class E to class C3 permitted development right which I wrote about in my 4 December 2020 blog post E = C3.

But first a few basic points to note about the way these cogs work:

1. Article 4 directions do not have to be approved by the Secretary of State but he can intervene where he considers that a direction is inappropriate.

2. Unless an article 4 direction takes effect at least a year after it was first publicised, in certain circumstances the authority can be liable to claims for compensation where someone can show they incurred abortive expenditure or otherwise suffered loss or damage as a result of the direction.

3. For permitted development rights where prior approval of certain matters is required before the right can be relied upon, the prior approval needs to be secured before the direction takes effect and needs to be completed within three years of prior approval.

The role of article 4 directions has increased with the gradual spread of “resi conversion” permitted development rights since 2013.

The office to residential permitted development right was first introduced in May 2013. At that time the legislation included a specific list of “excepted areas” within which the right did not apply, for instance London’s central activities zone. The Government was not adverse to threatening intervention where authorities sought to introduce blanket article 4 directions in relation to other areas, for instance its well publicised spat at the time with the London Borough of Islington.

In 2016 the right was made permanent. The list of excepted areas was scrapped but only as from 30 May 2019 so as to give affected authorities time to put article 4 directions in place as appropriate (see Lichfields’ 14 March 2016 blog post Office to Residential Permitted Development Right Made Permanent.

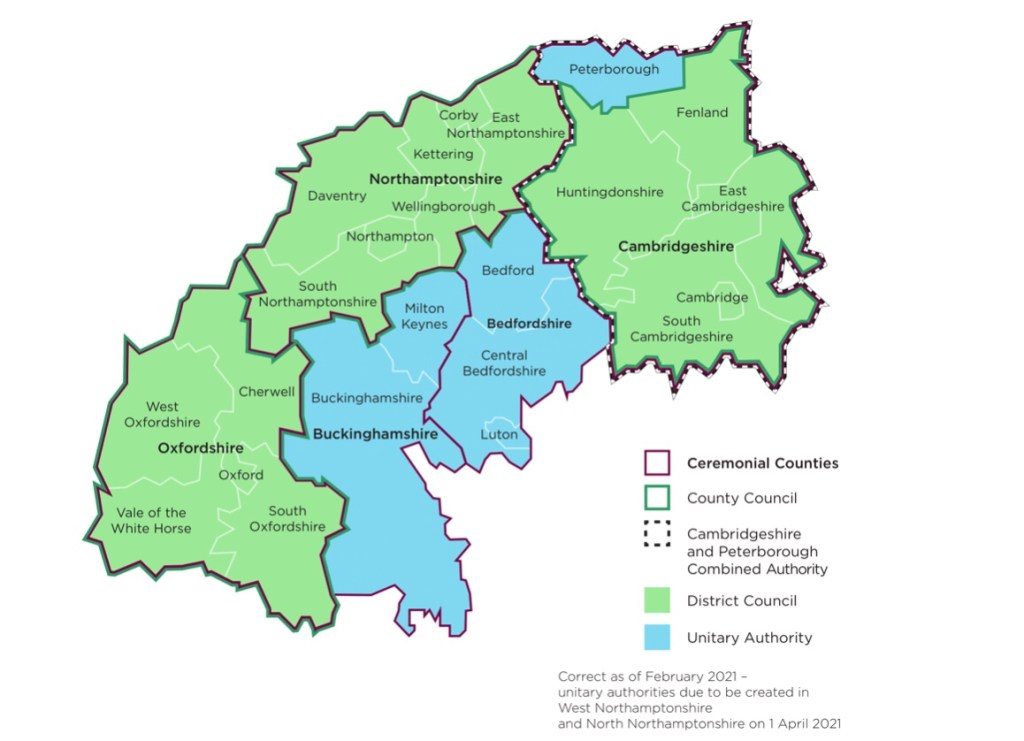

There is now indeed a patchwork of article 4 directions across the country, disapplying “resi conversion” permitted development rights in relation to many areas of the country. Focusing on central London, here is how the “offices to resi” rights is disapplied in RBKC and in Westminster for instance.

When Class E was introduced from 1 September 2020 (see my 24 July 2020 blog post E Is For Economy for more detail) existing permitted development rights were kept in place until 31 July 2021 (applying to what the uses would have been categorised as prior to the creation of Class E) so as to give the Government time to introduce new permitted development rights that apply to Class E.

The consultation period on the proposed new development rights closed on 28 January 2021 and the Government has come under fire from many quarters for the intended breadth of the new rights (for instance, here is the British Property Federation’s response). The statutory instrument to introduce the new rights (and in part replace the old rights, which will expire) has not seen the light of day and we are now around six months away from what might be termed PD-Day, 1 August 2021.

Some big questions arise and discussions within Town with Duncan Field and other partners and colleagues have been really useful. I’m not going to give away for free our entire Town “house view” but I’m just going to state the obvious:

⁃ the existing permitted development rights that attached to uses now within Class E will fall away after 31 July 2021, the end of the “material period” in the Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2020, unless secondary legislation extends the material period for those purposes, as a stop gap.

⁃ it is questionable whether existing article 4 directions would restrict the operation of any new permitted development rights that are introduced, even where the change is still, say, offices to residential (and some changes that, according to the Government’s consultation proposals, will now be possible are entirely new, e.g. restaurant, indoor sports hall or creche to residential).

⁃ As a matter of principle an article 4 direction cannot be made in relation to a future permitted development right, so authorities’ hands are tied until the statutory instrument containing the new rights is actually made.

⁃ plainly there is no time for authorities to give a year’s advance notice in relation to any new article 4 direction that is to take effect from 1 August 2021, so any more immediate restrictions would expose authorities to the risk of compensation claims (unless there is some specific transitional arrangement in the new rights, for instance if the new rights would permit development that before 1 August 2021 have been restricted by an article 4 direction, but that will not be straight-forward at all).

It is interesting that when the “excepted areas” system was abolished in 2016 authorities were given sufficient time to put article 4 directions in place. In the rush this time round, either this issue has been overlooked or the Government is seeking to sidestep the article 4 direction process and create some kind of gold rush for prior approvals before directions can be introduced and take effect. After all its antipathy towards article 4 directions in the “resi conversions” area, save where exceptionally justified, is plain from its recent consultation on proposed changes to the NPPF:

“Article 4 directions

“We also propose clarifying our policy that Article 4 directions should be restricted to the smallest geographical area possible. Together these amendments would encourage the appropriate and proportionate use of Article 4 directions.”

“The use of Article 4 directions to remove national permitted development rights should

• where they relate to change of use to residential, be limited to situations where this is essential to avoid wholly unacceptable adverse impacts

• [or as an alternative to the above – where they relate to change of use to residential, be limited to situations where this is necessary in order to protect an interest of national significance]

• where they do not relate to change of use to residential, be limited to situations where this is necessary to protect local amenity or the well-being of the area (this could include the use of Article 4 directions to require planning permission for the demolition of local facilities)

• in all cases apply to the smallest geographical area possible.”

The flexibility introduced by permitted development rights is necessary and welcome but let’s not focus on that lever without making sure that there isn’t going to be an almighty crunch when it is pulled. What am I missing here folks?

Simon Ricketts, 27 February 2021

Personal views, et cetera

PS If you’re on Clubhouse, I’ll be joined by some other friendly planning solicitors, barristers and planners to talk about this and other topical planning law issues at 6pm on Tuesday 2 March, details here. Do join us!