Photo-sharing social media apps, weaponised by the smartphone camera, are changing our experience and expectations of place. Is the planning system, and the law of private nuisance, keeping up?

The London Evening Standard had a story for our times last night: Please stop ‘influencing’ on our doorsteps, Notting Hill residents tell ‘unapologetic’ Instagrammers.

At a personal level we have all become artists, influencers, curators, with our instant pics, filtered, composed, annotated. Fomo for you = dopamine for me. But zoom out and through endlessly snapping, sharing, liking and commenting, we are of course the product, the hive mind, the crowd source, working for the data mine, adding to the geo-cache, mapping ceaselessly where the sugar is in the city.

In this context, what sells a place? From outside in: a glimpse of the life style, the life, that could be yours. From inside out: unique views out onto a city. The two ugly i words: iconic, instagrammable.

Which all makes the parable of Fearn & others v The Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery (Mann J, 11 February 2019) so perfect.

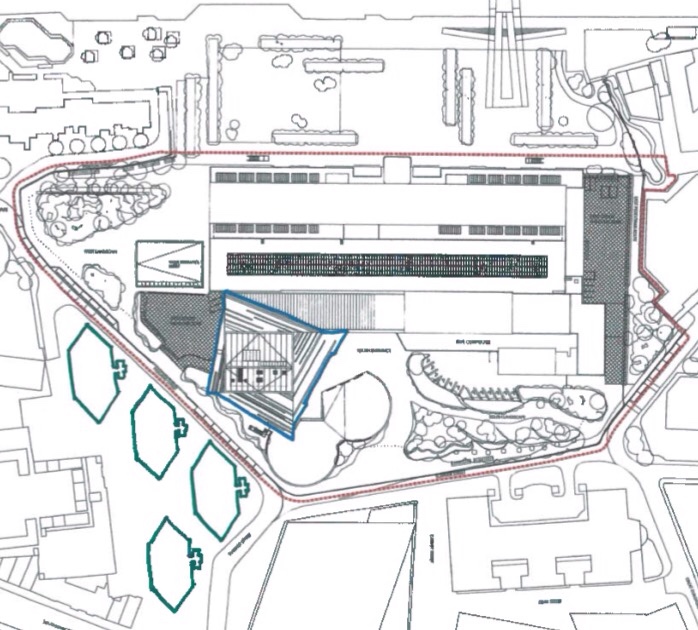

On one side, the residents of Neo Bankside, housed from floor to ceiling in glass so as to achieve spectacular views out and having paid no doubt precisely to be able to enjoy that experience.

On the other side, at its closest point 34 metres to the north of Block C of Neo Bankside, the viewing gallery on the tenth floor of the Blavatnik Building extension to Tate Modern, from which visitors also have spectacular views, including, to the south, of those residents in their transparent homes.

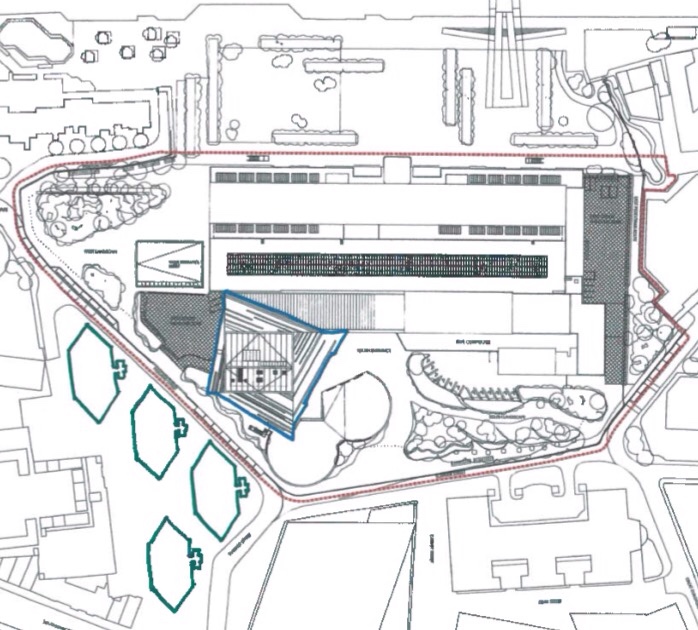

Plan A from the judgment (extract)

The people in the glass houses threw an expensive stone at their large neighbour, in the form of proceedings for an injunction to prevent overlooking from the viewing gallery, on the basis that it amounted to a breach of their rights to privacy, both under the law of private nuisance and, if the Trustees of the Tate were to be considered to be a public body, under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

What makes the situation particularly unusual is that the full implications of the juxtaposition of the two developments had not been appreciated by anyone, including the local planning authority (the London Borough of Southwark). The Tate proposals went through various design iterations. The judge found:

“On the balance of probabilities it is not likely that the planning authority did consider the extent of overlooking. It is more than plausible in all the circumstances that it did not, and I find that it was not given any focused attention by the planning authority.

So far as the developers of Neo Bankside are concerned, there is very little material on which to make a finding as to their awareness of the consequences of the viewing gallery. The developers were plainly aware of the nature of the Blavatnik development from time to time, and I accept Mr Hyslop’s evidence that there was consultation between the two sides. It is plain that the developers were aware of a viewing gallery because concerns were expressed as to the effect the flats would have on the viewing gallery (not the other way round). It is very likely that the developer was aware of the plans for the gallery during the concurrent planning process. However, I do not think that the developer foresaw the level of intrusion alleged by the claimants, and therefore to that extent did not foresee the consequences of its co-operation or its knowledge.

The end result of this analysis is that, so far as relevant, I find that all relevant parties were eventually aware of the viewing gallery in its present form, and aware of its function, but (so far as relevant) they did not think through the consequences of overlooking, and looking into, the flats in Block C.”

Whilst the planning system’s role does not extend to closing off all risks of nuisance actions from those affected by development, it is a shame that the full consequences of the juxtaposition of the viewing gallery and the flats were not appreciated at the time that the application for planning permission was determined so that the issue could have been considered as against Southwark’s planning policies that seek to protect residential amenity and the issue might have been pragmatically nipped in the bud.

One further complication appears to have been that the Neo Bankside development ended up being occupied other than visualised as at when planning permission was granted, with “winter garden balconies” ending up being subsumed as part of residents’ living space. Again, to what extent is it the role of the planning system to foresee issues of privacy and overlooking that may arise in consequence of internal changes such as this?

The judgment sets out the numbers of visitors that use the viewing gallery, potentially as many as 500,000 to 600,000 a year. The Tate has posted notices on the southern gallery asking visitors to respect the privacy of the gallery’s neighbours and has instructed security guards to stop people taking photographs of the flats and occupants. The judgment then describes the activities of the visitors and it is apparent that many take photographs of the flats.

“The claimants also rely on reports on social media as demonstrating a photographic and “peering” interest in the flats. They, and Mr May, produced in evidence a large number of photographs from social media, some accompanied by comments, which indicate that people have been to the gallery, noted that one can see into the flats, and commented in such a way as to acknowledge that there was a surprising intrusion into privacy arising as a result of that.

The first batch of postings were all dated in a period shortly after the Mail on Sunday wrote a piece about the issue in 2016. They are 14 Instagram posts which feature various photographs of the interiors of the Block C flats with some reflections on the lack of privacy in the flats. Some juxtapose the sign asking for respect for privacy with the view into the flats themselves; another has the rubric “Invading me some privacy”; another refers to the “Birds eye view directly into the neighbouring apartments. No wandering around in pj’s” with the hashtag (among others) “#noprivacy”. The general impression from that collection of posts, which caused upset to some of the occupants, was that those visitors were interested in peering into the flats when that view was on display.

This was supplemented by investigations into social media carried out by Mr May as part of his expert functions. A member of his firm carried out a check on Instagram and found 124 posts with photographs of Neo Bankside, apparently taken from the viewing gallery, in the period between June 2016 and April 2018. It was estimated by that member that they reached an estimated audience of 38,600, but there is a certain element of intelligent guesswork in that figure. Many of photographs show the interiors of the flats. Judging by their attached comments and hashtags, many of the photographs are taken because of the architectural interest of Block C, or because of the photogenic interest of the subject matter (not always the block by itself), and some comment on the fact that you can see right into the flats. Various conclusions can be drawn from this study, depending on one’s point of interest, but I consider that they support the case of the claimants that part of the interest on the part of at least some posters was in the view of Block C flat interiors from the gallery. For others the interiors are irrelevant, and for yet others it is noted and incidental, but there is a significant discrete interest in what one can see by looking into the flats.”

The judge’s conclusions on the level of intrusion were as follows:

“(a) A very significant number of visitors display an interest in the interiors of the flats which is more than a fleeting or passing interest. That is displayed either by a degree of peering or study, with or without photography, and very occasionally with binoculars.

(b) Occupants of the flats would be aware of their exposure to that degree of intrusion.

(c) The intrusion is a material intrusion into the privacy of the living accommodation, using the word “privacy” in its everyday meaning and not pre-judging any legal privacy questions that arise.

(d) The intrusion is greater, and of a different order, from what would be the case if the flats were overlooked by windows, either residential or commercial. Windows in residential or commercial premises obviously afford a view (as do the windows lower down in the Blavatnik Building) but the normal use of those windows would not give rise to the same level of study of, or interest in, the interiors of the flats. Unlike a viewing gallery, their primary (or sole) purpose is not to view.

(e) What I have said above applies to the upper three flats in this case. It applies to a much lesser extent to flat 1301, because that is rather lower down the building and the views into the living accommodation are significantly less, and to that extent the gallery is significantly less oppressive in relation to that flat.”

It is interesting that the judge does not comment as to whether what is done with the photographs taken, frequently uploaded and shared on social media, adds to the degree of intrusion.

After detailed legal analysis, the judge rejected the Article 8 claim on the basis that the Board of Trustees of the Tate Gallery is not exercising functions of a public nature.

He also rejected the claim in nuisance, but again after interesting analysis:

1. He finds that as a matter of principle there are situations where the law of nuisance can protect privacy, at least in a private home, both under traditional common law but also by giving effect to Article 8 by extending existing causes of action.

2. “That does not mean, of course, that all overlooking becomes a nuisance. Whether anything is an invasion of privacy depends on whether, and to what extent, there is a legitimate expectation of privacy. That inquiry is likely to be closely related to the sort of inquiry that has to take place in a nuisance case into whether a landowner’s use of land is, in all the circumstances and having regard to the locality, unreasonable to the extent of being a nuisance…”

3. The planning process is not by itself a sufficient mechanism for protecting against infringement of all privacy rights.

4. “The question is whether the Tate Modern, in operating the viewing gallery as it does, is making an unreasonable use of its land, bearing in mind the nature of that use, the locality in which it takes place, and bearing in mind that the victim is expected to have to put up with some give and take appropriate to modern society and the locale. Although there is an overall assessment to be made in order to comply with the tests referred to above, I shall approach the question by first breaking the consideration down into three elements – location, the use of the defendant’s property and the nature and use of the claimants’ properties.”

5. Tate’s legal submissions sought to place reliance on the fact that planning permission had been granted, drawing upon a statement by Lord Carnwath in Lawrence v Fen Tigers (Supreme Court, 26 February 2014):

“...a planning permission may be relevant in two distinct ways: (i) It may provide evidence of the relative importance, in so far as it is relevant, of the permitted activity as part of the pattern of uses in the area; (ii) Where a relevant planning permission (or a related section 106 agreement) includes a detailed, and carefully considered, framework of conditions governing the acceptable limits of a noise use, they may provide a useful starting point or benchmark for the court’s consideration of the same issues.”

6. In this case however the planning permission “provides little or no assistance…The level of consideration given to the overlooking, if there was any at all, is not apparent from the evidence that was placed before me.”

7. Nor were the planning policies for the area relevant as they did not “really engage with the important factors which have to be considered in considering a nuisance claim“.

8. “The other way in which Lord Carnwath suggested that the planning permission might be relevant is in providing evidence of the relative importance of the activity to the area. Since the planning permission in this case did not really address the viewing gallery, as opposed to the building as a whole, it is not possible to draw any conclusions from it as to the views of the planning authority on this point, so the permission is of no evidential use here either.”

9. The character of the locality is a significant relevant factor:

“The locality is, as appears above, a part of urban south London used for a mixture of residential, cultural, tourist and commercial purposes. That usage, thus described, does not say much about the privacy of high-rise glass-walled residential buildings. However, the significant factor is that is an inner city urban environment, with a significant amount of tourist activity. An occupier in that environment can expect rather less privacy than perhaps a rural occupier might. Anyone who lives in an inner city can expect to live quite cheek by jowl with neighbours. That is implicitly acknowledged by the claimants when they say they do not object to the fact that they are overlooked from the windows of the Blavatnik Building.”

Planning policies for the area “are of little or no assistance in determining what the current nature of the locality is. If they reflect the current usage, then they are irrelevant and add nothing. If they reflect a desire to move the area along to a different usage then they reflect the aspirations of the planners, but they do not affect what the nature of the locality should be treated as being for the purposes of the law of nuisance. In Fen Tigers the Supreme Court considered the question of whether the grant of planning permission could be taken to affect the character of a neighbourhood, and rejected the suggestion that that could be the case. The Justices considered the proposition that it might affect the character of the neighbourhood if it covered a large area but not a small area, and rejected that too (see eg Lord Neuberger at paras 86-88). If an actual planning decision cannot affect the character of the locality for the purposes of the law of nuisance, then the aspirations of a local authority for an area, as expounded in a local plan, should not be able to do it either. It therefore seems to me that the plans for the area do not bear on the character of the locality in this case.

Second, if I am wrong about that, then even if (as seems to be the case) there is an emphasis on cultural matters, and the benefits of a vibrant Tate Modern, it does not seem to me that that leads to the conclusion that this is an area in which a viewing platform should necessarily be actually expected in that context.

Third, while such generalised planning matters might be capable of resolving a conflict between a residential use and a cultural use (at least so far as planning is concerned), they do not assist in resolving the question of a conflict between a viewing platform (which is a particular subset of the cultural activities of the Tate Modern) and some residential accommodation.”

10. The operation of a viewing gallery is not an inherently objectionable activity in the neighbourhood.

11. Turning to what it is that the claimants complain about:

“They complain that their everyday life in the flats is on view because of the nature of the view. The nature of the view is the complete (or largely complete) view that one has of the living accommodation from the viewing gallery. It is that that is commented in one or two the Instagram postings. That arises (obviously) because of the complete glass walls of the living accommodation. I have considered whether the claimants would have had had a complaint if they had lived in flats designed with more wall and less window. If the owner/occupier/developer of such a flat would still have a complaint in nuisance, then so must the claimants. If he/she would not then I have to consider whether the claimants in this case would nonetheless have a cause of action themselves, arising out of the glass construction.”

The claimants would not have a nuisance claim if they lived in flats with more wall and less window.

“The developers in building the flats, and the claimants as successors in title who chose to buy the flats, have created or submitted themselves to a sensitivity to privacy which is greater than would the case of a less-glassed design. It would be wrong to allow this self-induced incentive to gaze, and to infringe privacy, and self-induced exposure to the outside world, to create a liability in nuisance. Other architectural designs would have reduced the invasion of privacy to levels which should be tolerated; that is the appropriate measure in my view. If the claimants have a design which raises the privacy invasion then they have created their own sensitivity and will have to tolerate what the design has created. I remind myself that the first designs for these flats did have some privacy protection built in.

In making that determination I am not indulging in any criticism of the claimants or the developers; nor am I criticising the architectural design. I am aware that is no part of the law of nuisance to discourage architectural adventure. However, the architectural style in this case (including the more striking design of the block as a whole) has the consequence of an increased exposure to the outside world for all the reasons contained in this judgment. That should not be allowed to alter the balance which would otherwise exist.”

“The winter gardens also have to be considered. A very material part of the perceived intrusion into privacy comes from the fact that the occupiers can be viewed in the winter gardens, which they treat as an extension of their living accommodation. Furthermore, the glass of the winter gardens allows a view to the glass of the internal double-glazed door, which in turn allows a further view into the living accommodation.

Those areas were not originally intended as part of the living accommodation. The planning documents make clear that they were conceived as a form of internal balconies, which the occupiers could enjoy as an additional amenity to their living accommodation. The experts both agreed on that. That is why the areas were single glazed, and not double glazed. The flooring was also intended to be different, to reflect that. They were not intended to be heated, though the developers did actually extend the under-floor heating into them. Had the occupiers operated their flats in that way then in my view they could have expected less privacy in respect of that part of their flats – one does not expect so much privacy in a balcony, even one as high as these. I agree with Mr Rhodes’ evidence to that effect.

In that respect, too, the owners and occupiers of the flat have created their own additional sensitivity to the inward gaze. They have moved more of their living activities into a quasi-balcony area and provided more to look at. Had they not done that, there would have been less worth looking at – less to attract the eye – and fewer living activities to be intruded upon. It is true that to a degree there would still have been a view through the winter gardens and through the double-glazed doors, and to that extent the privacy of the living accommodation would still have been compromised by something more usual (extensive glass doors giving on to a balcony-equivalent) but the whole package would have been a less sensitive one.”

12. Remedial steps could be taken, for instance by lowering solar blinds, installing privacy film or installing net curtains.

Recommendations for further reading

In true online tradition, if you liked this post [in fact whether or not you liked it] you will like Barbara Rich’s beautiful and reflective 15 February 2019 blog post Curtains For The Zeitgeist.

Simon Ricketts, 2 March 2019

Personal views, et cetera