The scale of the current crisis as to where and how to provide accommodation for asylum seekers can be viewed through a succession of High Court planning law cases over the last year or so. This blog post simply seeks to gather the cases in one place.

For context, there is much useful detail in a House of Commons Library research briefing, Asylum accommodation: hotels, vessels and large-scale sites.

Or here is how Thornton J pithily summarises the position in the most recent case (R (Clarke-Holland and West Lindsey District Council) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (Thornton J, 6 December 2023)):

“Since the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of asylum seekers requiring accommodation has reached unprecedented levels. The time taken by the Home Office to process asylum applications has slowed. The Home Office had for some time been “block booking” hotel accommodation for use by asylum seekers, a system by which hotel rooms are booked and paid for, usually at preferential rates, whether or not the rooms are in fact used. In October and November 2022, a “processing facility” at Manston became overcrowded. After the overcrowding at Manston, and in light of the increasing pressure on accommodation, the Home Office started to “spot book” hotels to accommodate the overflow. Spot bookings can be released without payment if they are not needed. This approach was controversial with the local authorities in whose areas the hotels were being booked and, in some cases, they sought injunctions to prevent the use of hotels for that purpose. Spot booking was intended as a short-term solution, but the absence of suitable alternative accommodation has led to the continued use of hotels booked in that way.

As a result of the strains on the asylum system, in January 2023, the Home Office approached the Ministry of Defence and other government departments enquiring about availability of Crown Estate assets which could be made suitable in the short term to assist with accommodating asylum seekers.”

One of the main issues which has come to the fore is whether planning permission required to house asylum seekers in hotels. Indeed this is the specific topic covered in a 17 February 2023 House of Commons Library insight paper .

In planning law, sometimes the easiest questions are the hardest, such as: is there a material change of use? We all know that difficulties particularly arise in relation to the use of properties for sleeping accommodation: for instance, where the boundary lines lie between dwellings, co-living developments, student accommodation, elderly living, hotels, hostels and emergency accommodation for those in need whether through homelessness or asylum seeking. I blogged about some of these issues way back in my 1 July 2016 blog post Time To Review The “C” Use Classes?

Since that House of Commons paper, whilst the issue has arisen in various applications by local planning authorities for injunctions to prevent such use, there has been no final determination of the issue. In fact, the lesson to draw from the (I think) only case where an injunction has been upheld, Great Yarmouth Borough Council v Al-Abdin (Holgate J, 21 December 2022), is that the question is specific to the relevant facts, circumstances and policy position in every case. In Great Yarmouth Holgate J upheld an application for the continuation of an interim injunction “restraining the defendants from using or facilitating the use of the Villa Rose Hotel, 30-31 Princes Road, Great Yarmouth, or any other hotel within an area protected by Policy GY6 of the Great Yarmouth Local Plan Part 2, adopted in December 2021, as a hostel, whether for the accommodation of asylum seekers or at all.”

Holgate J did not need to reach a final conclusion as to whether the use of the hotel was in breach of planning control, but simply had to determine by applying the “balance of convenience” test whether the injunction should continue in effect. However, he did state the following:

“Planning considerations are to do with the character of the use of land. It is common ground that the policies of the development plan may be relevant to that issue. See, for example, Wilson v West Sussex County Council [1963] 2 QB 764, 785. In my judgment Policy GY6 is certainly relevant. It is aimed at protecting a substantial part of the local economy of the borough dependent on tourism. That, in turn, is said to depend upon a collection of tourist facilities, including hotel accommodation.”

“There are some factors pointing against a hostel use. Proposed use would involve no alteration of the premises and in many ways the operation of the premises would be similar to that carried out ordinarily by hotel operators. There would be no dormitories and it is not suggested the accommodation is basic or inexpensive.

On the other hand, there are factors pointing to a hostel use. In this case, unlike others, the Council is aware of how the premises would be used. In part this is based upon their experience of the use of the Victoria Hotel. The premises would be block-booked for a substantial period of time, solely for occupation by people belonging to one cohort, asylum seekers, having nowhere else to live. In addition, as Mr Glason points out, there would be a degree of management of movement of the residents. They are not supposed to be absent for more than three days. The duration of their transient occupation would be determined by their move to the next stage of the asylum process. The accommodation would be paid for ultimately by the Home Office. As I have said, the location of the hotel within the Seafront Area in Policy GY6 is important. The claimant may rely upon that policy as a factor indicating that there would be a breach of planning control.

I have already referred to the increase in the 21-day average stay to something of the order of 26 weeks. There is no suggestion that that period is likely to decrease. The hotel would be closed to public bookings both as regards accommodation and the restaurant. There would be little or no expenditure by asylum seekers in the town. It strikes me that that is a highly relevant factor. They would not contribute to the local economy. Policy GY6 resists hostel use for what have been judged to be sound planning and economic reasons. This is a policy which is highly specific. It does not, for example, cover the whole of the borough or the whole of the town. Instead, it is targeted at the most important part of the town for tourism. It applies to a carefully defined strip of land closely related to the major tourist attractions.

At the end of the day whether a material change of use would occur is a question of fact and degree, but in my judgment the particular policy considerations raised in this case by Policy GY6 strengthen the Council’s case on breach of planning control significantly.”

There are two important specific points to bear in mind with this ruling:

First, the relevant local plan policy:

“In my judgment, GY6 is a highly specific, protective policy directed to a large and highly important sector of the Borough’s economy. Mr Glason provides helpful context for the policy. In 2019 the annual value of tourism to Great Yarmouth was around £648 million, supporting around 9,600 full-time tourism jobs and 13,000 tourism-related jobs, representing 37 per cent of total employment within the Borough. A recent economic report indicates that accommodation and food services is likely to be the second largest growth sector in the Borough after government services.”

Secondly, there had already been an enforcement notice in relation to change of use from the hotel to use as a house in multiple occupation, which does not appear to have been subject to any appeal. The judge considered that accordingly, “the present case is one where the apprehended breach of planning control has a flagrant character. “

The case is to be contrasted with earlier cases where Holgate J refused equivalent applications:

First, in Ipswich Borough Council v Fairview Hotels (Ipswich) Ltd v Serco Ltd and East Riding of Yorkshire Council v LGH Hotels Management Limited (Holgate J, 11 November 2022). This judgment contains, at paragraphs 72 to 83, useful analysis as to the distinctions between a hotel and a hostel in planning law terms. At paragraph 101 he states that the “distinction between hotel and hostel use in a case of the present kind is fine. There are some factors pointing against a hostel use. The proposed use involves no alteration of the premises. In many ways the operation of the Novotel would be similar to that carried out ordinarily by the hotel operators. There would be no dormitories and the accommodation could not be described as basic or inexpensive. On the other hand there are factors pointing to a hostel use. The premises would be block-booked for a substantial period of time solely for occupation by people belonging to one cohort, asylum seekers, having nowhere else to live. The duration of their transient occupation would be determined by their move to the next stage of the asylum process. The accommodation would be paid for ultimately by the Home Office. It is arguable that the factors pointing towards a hostel use outweigh those pointing against.

The effect of the block-booking of the whole hotel is that no accommodation is available for any member of the public. It is said that the Novotel is the largest hotel in the centre of Ipswich and that the loss of the accommodation would be damaging to the hospitality and leisure economy of the town, given its close proximity to restaurants and bars. It is arguable that this alleged harm is a planning consideration which may render a change to a hostel a material change of use and so attract planning control.”

At paragraph 110: “In each case before this court there are factors pointing for and against the proposed use being a hostel use. Even if a hostel use would be involved, the key question still remains whether it would represent a material change of use. That would depend upon the planning consequences of the change. In each case that turns upon the planning harm identified by the claimant.”

Secondly, in Fenland District Council v CBPRP Limited (Holgate J, 25 November 2022) which related to the use of a hotel in Wisbech, Lincolnshire. Holgate J refers back to his analysis in Ipswich.

Am injunction was similarly not upheld in The Council of the City of Stoke-on-Trent v Britannia Hotels Limited (Linden J, 2 November 2022) (I don’t have a link to that judgment I’m afraid).

An injunction was also not upheld in relation to the use of the Stradey Park Hotel in Llanelli. On 7 July 2023, Gavin Mansfield KC, sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge, dismissed an application by Carmarthenshire County Council for an injunction prohibiting the use of the hotel for housing asylum seekers.

In subsequent proceedings, Roger ter Haar KC , sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge, granted an injunction to restrain unlawful protest activity against the use of the hotel for those purposes. (Again, no links to these judgments I’m afraid).

And, indeed, the Planning Court has also been kept busy on the wider issues arising.

In R (Parkes) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (Holgate J, 11 October 2023), Holgate J rejected an application for judicial review that sought to establish that the Home Office’s proposed use of the Bibby Stockholm barge, moored in Portland Harbour, for the accommodation of asylum seekers, was unlawful, in part, it was submitted, because planning permission would be needed for such use. As a matter of principle the judge considered that the claim was misconceived: it was for the local planning authority in the first instance to determine whether the proposed use was in breach of planning permission and whether it would be expedient to enforce against any breach. But in any event the barge was below the low water mark and therefore beyond the scope of planning control.

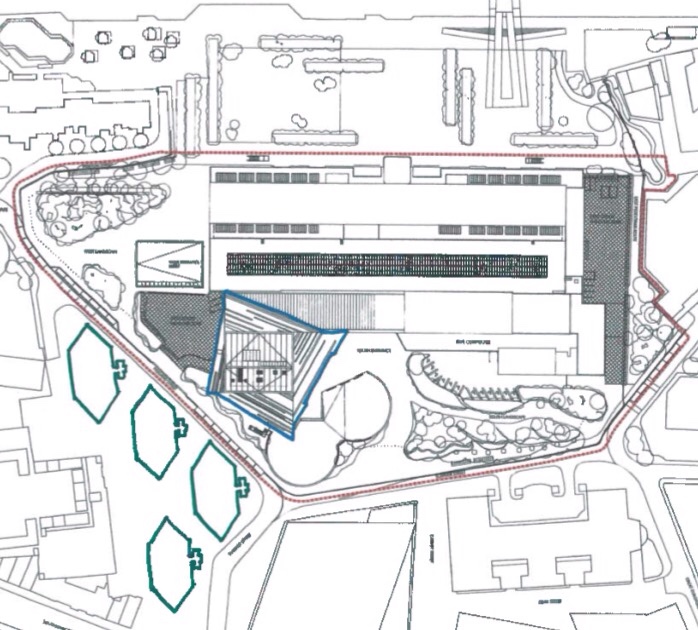

In R (Clarke-Holland and West Lindsey District Council) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (Thornton J, 6 December 2023) (which followed a related judgment of the Court of Appeal on 23 June 2023 which held that section 296A of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 was a statutory bar to an injunction being upheld against the Government in the case), Thornton J rejected applications for judicial review brought seeking to challenge the lawfulness of the Home Office’s reliance on class Q of the General Permitted Development Order allowing development on Crown land in an emergency in connection with the proposed use of RAF Wethersfield in Essex and RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire for the accommodation of asylum seekers.

I usually end with some flippant closing comments but not today. Behind each case lies much human misery.

Simon Ricketts, 14 January 2024

Personal views, et cetera

Extract from photograph by Marcus Spiske courtesy of Unsplash