Time is money. Time is unmet needs. Time is unrealised public benefits.

I just wanted to capture some of the current, frankly depressing, data that is out there on application and appeal timescales.

The purpose of this post is to underline that there is a significant problem to be addressed. What to do about it will be for another post – there is certainly much that can be done that does not require (1) legislation (2) additional resources or (3) any procedural shortcuts.

Applications

A piece from yesterday’s Planning daily online: Council signs off 2,380-home urban extension almost four years after committee approval (£). Four years is certainly going it some but I can confirm from constant first-hand experience how difficult it can be to move a project from resolution to grant to permission at any speed. The larger or more complex the project, the longer those negotiations over the section 106 agreement and associated aspects can end up taking.

My colleague Lida Nguyen has been looking at the position in London. She has looked at all applications for planning permission which were referred to the Mayor between 3 January and 11 December 2020, so applications of potential strategic importance as defined in the Mayor of London Order 2008 and, for those which were then approved by the relevant borough (without intervention by the Mayor or secretary of State), she has looked at the average time that the application took from validation to the borough’s resolution to approve and from the borough’s resolution to approve to permission being issued. Discarding a few anomalous cases, this left 88 to be analysed.

In my humble view the statistics are appalling, but not surprising:

Application submission to resolution to approve

Median: 228.5 days

Mean: 269 days

Resolution to approve to grant of permission

Median: 218.5 days

Mean: 259 days

It’s rather deflating for applicants and (when you stand back from the detail) surely absurd that resolution to grant in reality only marks the halfway point to a permission in relation to significant projects in London. Wouldn’t it be a start for boroughs, the Mayor and those acting for applicants to set a target of halving each of those figures and agreeing the necessary steps to achieve that reduction?

Appeals

My 25 May 2019 blog post Pace Making: Progress At PINS reported on Bridget Rosewell’s recommendation, adopted by the Planning Inspectorate, that inquiry appeals decided by an inspector (i.e. not recovered by the Secretary of State) should be decided within 24 weeks of receipt and that where the Secretary of State is to be the decision-maker, inspectors’ reports should be submitted to the Secretary of State within 30 weeks of receipt of the appeal. Initial progress was really impressive – until the first lockdown struck in March 2020. After a slow start (see my 2 May 2020 blog post There Is No E In Inquiry), PINS of course eventually, to the massive credit of all involved, embraced virtual hearings, inquiries and examinations and the risk of an impossible backlog was averted. However, it is clear from the latest Planning Inspectorate statistical update (19 August 2021) that there is still much work to do:

“The mean average time to make a decision, across all cases in the last 12 months (Aug 20 to Jul 21), was 27 weeks. The median time is 23 weeks.

The median time to decide a case decreased by 0.6 weeks between June and July 21, with the median being 21.4 weeks.

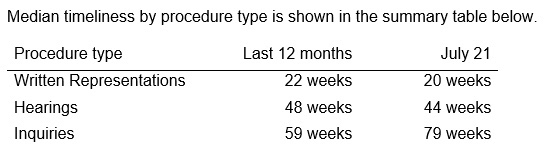

Median timeliness by procedure type is shown in the summary table below.

Performance since April 21 against the median measure has only varied by 0.7 weeks, between 21.4 weeks and 22.1 weeks. Performance had been improving between November 20 and March 21. For inquiries, in the last two months, cases have taken longer to decide as a result of very old enforcement inquiry cases being decided.

Enforcement decisions made in the last 12 months had a median decision time of 34 weeks. Looking at the annual totals, the median and mean time to decision for specialist decisions have been broadly the same as for enforcement decisions, and longer than the median for planning decisions. Since February 21 there has been a change in this trend, with Specialist cases being quicker than Enforcement.

The median time for planning appeals decided by inquiry under the Rosewell Process over the 12 months to July 21 is 35 weeks. This is quicker than other types of casework decided by inquiry.”

Whilst the extent of statistical information provided these days is welcome, it is difficult sometimes to track the figures through the different tables so as to work out what the likely timescale outcome for a prospective appellant will turn out to be. I have also looked in vain within the statistics for any information as the time being taken between appeal receipt and validation – a traditional black hole when it comes to appeal timescales. I’m also struggling to see any breakdown as to what the “Rosewell” inquiries were (35 weeks average) as compared to inquiries overall (79 weeks!).

That overall 27 weeks average is deceptively encouraging for anyone looking at anything other than a written representations appeal. Because those appeals make up 95% of the total of course they massively skew the mean figure. But even then, although not reflected in these statistics, my own anecdotal impression is that validation of appeals which proceed by way of written representations or hearing is very slow indeed, raising a large question mark over the overall statistics. Possibly something to do with the focus on Rosewell inquiry appeal targets. Am I being unfair? What solid information on this is there out there? If there isn’t any, why not??

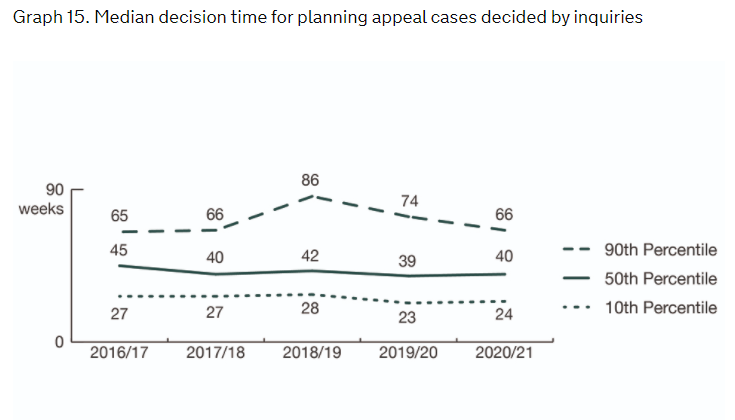

The Planning Inspectorate Annual Report and Accounts (July 2021) contains further statistical information, with tables such as these looking back at the changing position over the last five years:

In order to meet Rosewell targets, surely on that last table the 90th percentile needs to come down from 66 weeks to 24 weeks – and to be measured from receipt of appeal rather than validation?

Again, as with timescales for major applications in London, with appeal inquiries, surely we are looking at the need to more than halve current timescales?

All tables above have been taken from PINS documentation, for which thanks.

Simon Ricketts, 20 August 2021

Personal views, et cetera

Planning Law Unplanned is having a summer break this week, before returning at 6pm on Tuesday 31 August for somewhat of a BECG/DP9 special, London Elections 2022: Politics Meets Planning. Join the club here for notifications of this and future clubhouse Planning Law Unplanned events.