As set out in his 16 November 2017 written ministerial statement, the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government has written to 15 local planning authorities (Basildon, Brentwood, Bolsover, Calderdale, Castle Point, Eastleigh, Liverpool, Mansfield, North East Derbyshire, Northumberland, Runnymede, St Albans, Thanet, Wirral and York), indicating that they have “the opportunity to put forward any exceptional circumstances, by 31 January 2018, which, in their view, justify their failure to produce a Local Plan under the 2004 Act regime.” He will then make a formal decision as to whether formally to intervene in their plan-making.

His Bristol speech on the same day says this:

“…today is the day that my patience has run out.

Those 15 authorities have left me with no choice but to start the formal process of intervention that we set out in the white paper.

By failing to plan, they have failed the people they are meant to serve.

The people of this country who are crying out for good quality, well-planned housing in the right places, supported by the right infrastructure.

They deserve better, and by stepping in now I’m doing all I can to ensure that they receive it.”

Will this be another empty threat or this time will we actually see some action? Back 20 July 2015 the then minister for housing and planning, Brandon Lewis, announced in a written ministerial statement:

“In cases where no Local Plan has been produced by early 2017 – five years after the publication of the NPPF – we will intervene to arrange for the Plan to be written, in consultation with local people, to accelerate production of a Local Plan.”

There was then the February 2016 technical consultation on implementation of planning changes which included within its chapter 6 the Government’s proposed criteria for intervention, namely where:

* the least progress in plan-making had been made;

* policies in plans had not been kept up to date;

* there was higher housing pressure; and

* intervention would have the greatest impact in accelerating local plan production.

Decisions on intervention would be informed by the wider planning context in each area (specifically, the extent to which authorities are working co-operatively to put strategic plans in place, and the potential impact that not having a plan has on neighbourhood planning activity).

The Government confirmed in its February 2017 housing white paper that these criteria would indeed be adopted.

The February 2016 technical consultation proposed that authorities identified for potential intervention would be given an opportunity to set out exceptional circumstances why that should not happen:

“What constitutes an ‘exceptional circumstance’ cannot, by its very nature, be defined fully in advance, but we think it would be helpful to set out the general tests that will be applied in considering such cases. We propose these should be:

• whether the issue significantly affects the reasonableness of the conclusions that can be drawn from the data and criteria used to inform decisions on intervention;

• whether the issue had a significant impact on the authority’s ability to produce a local plan, for reasons that were entirely beyond its control.”

We can assume that those 15 authorities will now be looking very carefully at this passage.

A political decision to intervene is one thing but what would then be the legal process to be followed?

The Housing and Planning Act 2016 amended the default powers of the Secretary of State within section 27 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004, so that it read as follows:

Under section 9 of the Neighbourhood Planning Act 2017, the Secretary of State can now also order the preparation of joint development plans, giving him a further option in the case of interventions, particularly as he “may apportion liability for the expenditure arising on such basis as he thinks just between the local planning authorities for whom the document has been prepared.”

Of course the practicalities are quite another thing. How is the Government actually going to go about the intervention process? Preparing the document centrally, directing an adjoining authority to take the lead or parachuting in civil servants or consultants to carry out the work (all at the cost of the authority) is surely always going to be a last resort. The process is likely to be locally unpopular, prone to error and obviously liable to litigation. Authorities may also trip over themselves in their belated haste. However, surely after the end of January a few authorities are bound to be identified, pour encourager les autres.

So how have these authorities found themselves in this position? Here’s just a flavour:

Basildon

Yellow Advertiser (20 April 2017):

“Tory chief Phil Turner has suggested calling in independent analysts to go over the plan, which allocates land for development across the borough until 2034.

Cllr Turner said he hoped to ask experts to go over the plan’s policies on green belt and infrastructure.

He said he hoped the move would help him cut the number of planned houses in the borough, which currently sits at 15,260.

He said: “We can’t review the whole plan but those two points are areas where we think there may be opportunities about reducing our housing numbers.

“During the consultations, we’ve had a lot of feedback about how people don’t think we are working hard enough to to save the green belt. We don’t want to build on the green belt and we have avoided it as much as possible but I don’t think the public actually believes us.

“So what we are thinking is we should call in some independent people to scrutinise the plan and tell us where we can maybe use the evidence to put up an argument to challenge the housing numbers.”

Cllr Turner was due to present the proposal to all councillors in a secret meeting last night.

If approved, he said the process could cost a six-figure sum and take up to six months.”

Brentwood

Largely green belt authority. Prolonged delays.

Bolsover

Local Plan withdrawn after it failed examination in 2014. Failure to co-operate with North East Derbyshire District Council and Chesterfield Borough Council with regard to a strategic development site.

Calderdale

Brighouse Echo (17 November 2017):

“Councillor Scott Benton, Leader of the Calderdale Conservatives, said: “‘The draft Local Plan published by the Labour Council administration has caused great concern throughout the different communities of Calderdale.

“The Labour Party have clearly been taken aback by the scale of the opposition to their plans and instead of meeting their target of producing a Final Plan in December, they have announced that they are now kicking the issue down the road again until after the elections next summer.

“‘Labour’s first attempt at producing a draft Plan was a disaster. Instead of working with residents and other Councillors to produce a Plan that is fit for purpose they have delayed the process until after elections. This makes a mockery of our local democracy and demonstrates why Calderdale requires fresh leadership.”

Castle Point

Local Plan failed examination in April 2017 – failure adequately to assess housing need, and failure to cooperate with neighbouring councils.

Eastleigh

Eastleigh News (16 November 2017):

“In February 2015, Eastleigh had to go back to the drawing board after its first Local Plan was rejected by the planning inspector because, he said, it didn’t plan for enough new homes – in particular new affordable ones.

On December 11 the council will meet for a crunch vote on their new Local Plan and the council’s preferred options of housing development on land North of Bishopstoke and Fair Oak (Options B and C).

There has been fierce local opposition – not just from the residents most likely to be affected by the development of 5,000 new homes but also from residents close to the route of a proposed M3 link road that will stretch across countryside from Upham to Allbrook.

So far this year three councillors have stood down from the ruling Liberal Democrat group to sit as Independents because of their concerns over the direction of the local plan.

It is likely they will join the opposition Conservative group on December 11 in voting against the council’s favoured options – though this is unlikely to prevent their adoption.”

Liverpool

Prolonged delays.

Mansfield

Mansfield 103.2 (17 November 2017):

“Hayley Barsby, Interim Chief Executive at Mansfield District Council, said: “We are disappointed to have been named as one of the 15 local authorities.

“We are confident that while we don’t have an up-to-date Local Plan that this hasn’t affected development in the district.

“Mansfield District Council is committed to bringing forward house building – this is demonstrated by the council supporting the Berry Hill development (formerly known as the Lindhurst development) which will create 1,700 new houses for the district.

“Of the 9,024 new homes we need to provide by 2033, planning permission already exists for 4,147.

“Over the past 12 months we have worked hard to bring forward the Local Plan and during this time we have been mindful to undertake feasibility and consultation to ensure it reflects not only the needs of the district but also the views of our communities.

Following an initial consultation in early 2016 on the draft Local Plan, we received 1,477 comments which were then reviewed to ensure the plan is fit for purpose up to 2033.

The council reviewed its position and prepared a new vision and objectives. These have been used to create alternative options for the delivery of sustainable housing and employment to meet future requirements.

A Preferred Options consultation took place in October and November 2017.”

North East Derbyshire

Derbyshire Times (18 October 2017) quotes the Labour leader of the council in response to criticisms from the local (Conservative) MP:

“We are well aware of the need to protect the character of our area and have done all we can to do this, however the Government’s expectations and targets for housing place significant pressure on our ability to continue this.”

He added: “As such we’d welcome any moves by the MP to seek a revision to Government policy so that the expectations for north east Derbyshire are realistic and in keeping with those of our residents.”

Northumberland

Northumberland Gazette (16 November 2017):

“Northumberland’s Local Plan, a key document which details where development should take place, is not likely to be adopted until 2020. In the summer, the county council’s new Conservative administration withdrew the Local Plan Core Strategy – put together by the council’s Labour group before losing the county election in May – to review a number of aspects of the document, primarily due to concerns that numbers for the proposed level of new housing were too high.”

Runnymede

Local plan failed examination in 2014 due to failure to meet housing needs and failure of duty to co-operate.

St Albans

Local Plan failed examination in 2016 due to failure of duty to co-operate, council’s subsequent challenge to that decision failed.

Thanet

Prolonged delays but Regulation 19 consultation anticipated in January 2018.

Wirral

Wirral Globe (16 February 2017):

“Wirral Council’s leader is preparing for battle with Whitehall over plans that could force the authority to turn green belt land into a housebuilding free for all.

The Government has ruled Wirral must produce a blueprint demonstrating how it will hit a target of building nearly 1,000 new homes each year over the next five years.

That’s 500 more than the present annual number.

Councillor Phil Davies says he is adamant that he will not sanction the release of green belt land – and has written to communities secretary Sajid Javid urging him to reconsider.”

York

Prolonged delays.

York Press (16 November 2017):

“City of York Council’s Conservative and Liberal Democrat leaders have pointed to delays caused by the announcement of barracks closures in York, and insisted they are on course to deliver a sound plan by May.

Leader Cllr David Carr said: “We’re making very good progress to deliver a Local Plan which is right for York – one which provides the homes and employment opportunities we need while protecting our city’s greenbelt and special character.

“We rightly reviewed the plan after the Ministry of Defence’s announcement over the future of three very large sites, and consulted once again listen to views from across York.”

…

However the announcement has brought criticism from Labour councillors, who say they warned this could happen.”

Themes

Tell me if I am over-simplifying but it seems to me that there are some common, unsurprising, themes within this list:

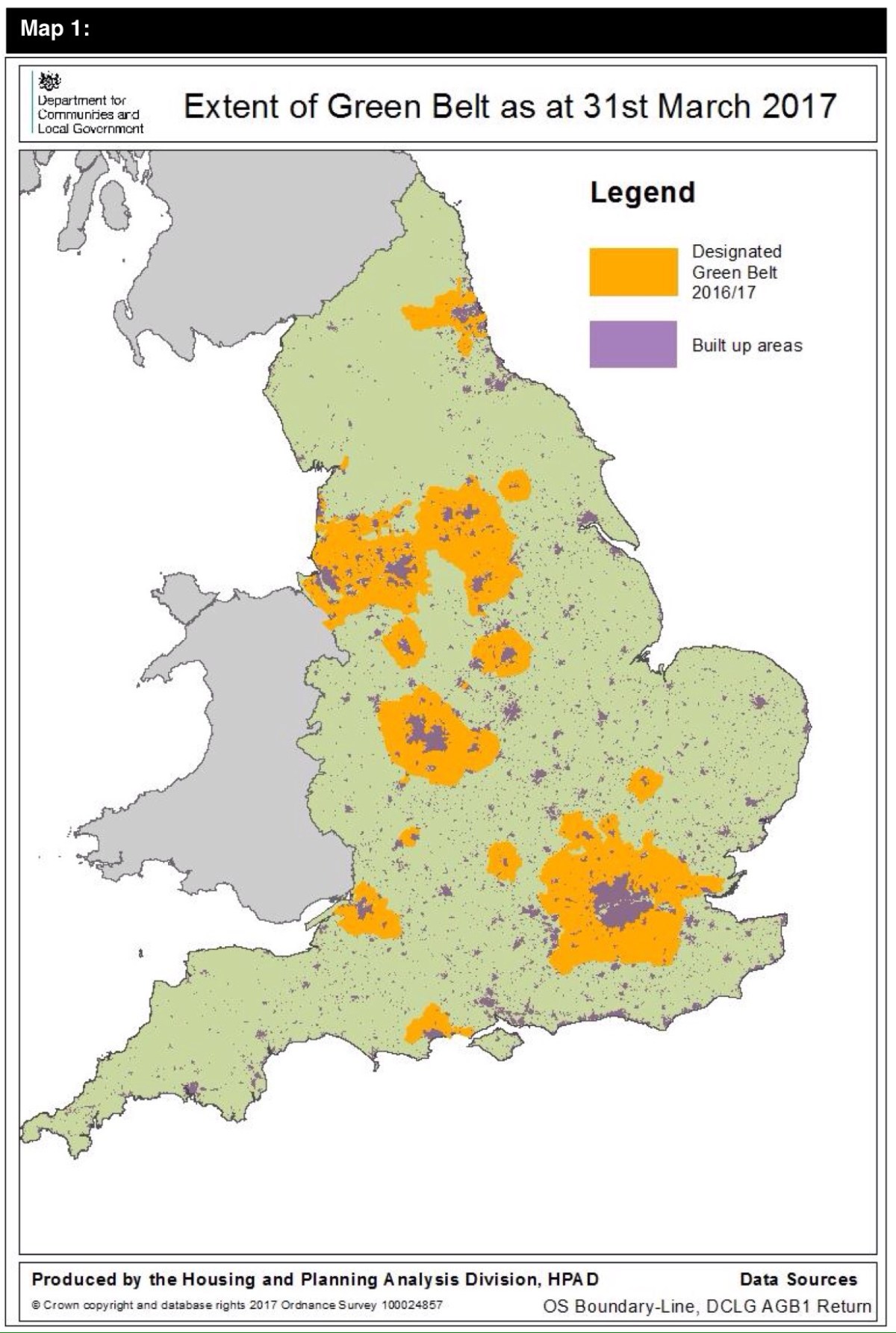

– Uncertainties as to the calculation of objectively assessed needs and the extent to which authorities can justify not meeting that need to due to green belt issues (nearly all these authorities have areas of green belt within their boundaries).

– Uncertainties as to the extent to which it may be appropriate for authorities to assist in meeting other authorities’ needs, the duty to co-operate being far too loose a mechanism (which is not necessarily to suggest that a return to regional planning and “top down” numbers is the answer – these are authorities who didn’t manage to adopt a plan even under that regime, which of course had built into it inherent delays at the regional tier).

– As a result of this wriggle room, housing numbers becoming a political battleground, with members often not accepting officers’ advice or with changes in approach arising from changes in political control.

– Delays due to plans having been found unsound at the end of, or a long way into, a long process (usually as a result of these factors).

– Plainly, these authorities haven’t been sufficiently spurred on by the application of the “tilted balance” leading to development taking place in unplanned, unwanted locations – perhaps due to that policy lever being less effective in relation to green belt – or other Government threats to date.

– Many of the authorities being, on paper at least (their websites tell a good story to their constituents), now close to being able to submit a plan for examination, after (usually) a series of Regulation 18 consultation processes.

Is slow plan-making the fault of local politicians or of the planning system itself? I would say both. The lack of prescription as to numbers and methodology has inevitably given room for protracted, unending, debate as to different approaches and outcomes. Debate and local choice is surely to be welcomed but the system has been so loose that in some areas this has slowed progress to an extent that anyone would surely say was unacceptable. Accordingly, the proposed tightening of the OAN methodology (see my 20 September 2017 blog post) and of the duty to co-operate is surely welcome, as is this clear threat by Javid of intervention.

However, if formal intervention is actually required, the outcome will surely be a political, administrative and legal mess.

…………………..

Meanwhile, it is perhaps unfortunate timing that in the same week the Secretary of State has made a holding direction in relation to the Stevenage local plan, at the request of local Conservative MP Stephen McPartland, despite a favourable Inspector’s report having been received last month. The issue appears to result from a continuing fault line both in Stevenage and more widely: whether to provide homes by way of town centre redevelopment (as per the plan) or outside the town in a new settlement (as per Mr McPartland).

Whatever the rights and wrongs of the Stevenage position, why allow such political interventions if the plan has been found sound?

Simon Ricketts, 18 November 2017

Personal views, et cetera

(With thanks to Town Legal colleague Rebecca Craig for some background research. Mistakes and opinions all mine).