Exactly a week after the Westferry Printworks decision letter (see my previous blog post) on 22 January 2020 the Secretary of State allowed two further appeals in relation to significant London residential development projects, this time both decisions following his inspectors’ recommendations, and with costs awards in favour of the appellants, again as recommended by his inspectors.

Given that an award of costs can basically only be made on the basis of unreasonable behaviour by a party to the appeal (see the detailed advice in the Government’s Planning Practice Guidance), lessons plainly need to be learned – in fact what happened in both cases was pretty shocking.

North London Business Park site, Barnet

This was an appeal by Comer Homes Group against Barnet Council’s refusal of a hybrid application for planning permission for the phased comprehensive redevelopment of the North London Business Park to deliver a residential led mixed-use development:

• detailed element comprising 376 residential units in five blocks reaching eight storeys, the provision of a 5 Form Entry Secondary School, a gymnasium, a multi- use sports pitch and associated changing facilities, and improvements to open space and transport infrastructure, including improvements to the access from Brunswick Park Road, and

• outline element comprising up to 824 additional residential units in buildings ranging from two to eleven storeys, up to 5,177m2 of non-residential floorspace (Use Classes A1-A4, B1 and D1) and 2.9 hectares of public open space, associated site preparation/enabling works, transport infrastructure and junction works, landscaping and car parking.

This is the Secretary of State’s decision letter and inspector’s report in relation to the appeal and this is the Secretary of State’s decision to make a full costs award against the council, following the inspector’s recommendations.

Members had refused the application against officers’s recommendations.

The council’s failing is set out starkly in the inspector’s costs report: no proper evidence was adduced to support its decision:

“Mr Griffiths, Principal Planning Officer at the Council of the London Borough of Barnet, was the Council’s only witness at the Inquiry. He stated, in his proof of evidence, that “It is not the intention for this document to represent my professional opinion and the evidence presented represents the views of elected members of the London Borough of Barnet Planning Committee”.

The proof of evidence focusses on a particular view contained within a TVIA submitted by the Applicant and states that “Within View 11, the 8-storey height of Blocks 1E and 1F stands in harmful juxtaposition with the two-storey height of the properties on Howard Close”. But the proof acknowledges “…that buildings of up to 7 storeys in height could be acceptable in this location therefore it is pertinent to outline the additional harm that would arise from the 8 and 9 storey buildings proposed within the development and why these heights are unacceptable”.

The written evidence fails to substantiate why the extra storey on Blocks 1E and 1F would cause harm and fails to consider the effect of buildings over seven storeys in height elsewhere in the development. The proof simply repeats the assertion made in the sole reason for refusal of the application that “The proposed development, by virtue of its excessive height, scale and massing would represent an over development of the site resulting in a discordant and visually obtrusive form of development that would fail to respect its local context…to such an extent that it would be detrimental to the character and appearance of the area”.

Under cross examination Mr Griffiths refused to answer some questions put to him and to give his professional view on the effect of the proposed development on the character and appearance of the area. The Appellant was not thus afforded the opportunity, at the Inquiry, to explore the unsubstantiated assertions made in the proof of evidence and did not learn anything more about members concerns. Crucially, no member of the Planning Committee appeared at the Inquiry to substantiate their views that was unsubstantiated in the proof of evidence.

The Council has failed to produce either written or verbal evidence to substantiate the reason for refusal of the application, and has provided only vague and generalised assertions, unsupported by an objective analysis, about the proposed development’s impact. The Council has behaved unreasonably and the Appellant has incurred unnecessary expense in the appeal process. A full of award of costs against the Council is justified.”

It was hardly surprising that the Secretary of State decided to allow the appeal:

“32. The development plan restricts tall buildings to identified locations, and the proposal would include them on a site not identified as suitable for them. This conflict carries significant weight against the proposal.

33. The proposal has been designed to respect the existing character of the local area, while maximising the potential for delivering homes. It would deliver a replacement secondary school alongside new open space, sports facilities and community space. The local authority is unable to demonstrate a five-year supply of housing land without taking account of this site, and the proposal would provide 1350 new homes. The provision of the housing and the ancillary facilities both carry significant weight in favour of the proposal.

34. The Secretary of State considers that there are material considerations which indicate that the proposal should be determined other than in accordance with the development plan, and therefore concludes that the appeal should be allowed and planning permission granted.”

The inquiry sat for four days in October and November 2018 (why the inordinate delay since then?), with the appellant team comprising Christopher Katkowski QC and Robert Walton (now QC), calling four expert witnesses. The costs award will amount to a sum that would be ruinous for many private sector bodies, well into six figures – because council members took a decision without evidence and without considering whether proper evidence, or a different approach, might be required in the face of an appeal. And a scheme for well over a thousand homes and a school (first applied for in December 2015!) has been delayed for absolutely no reason.

Conington Road, Lewisham

This was an appeal by MB Lewisham Limited against Lewisham Council’s decision to refuse its application for planning permission for the construction of three buildings, measuring 8, 14 and 34 storeys in height, to provide 365 residential dwellings (use class C3) and 554 square metres (sqm) gross of commercial/ community/ office/ leisure space (Use Class A1/A2/A3/B1/D1/D2) with associated access, servicing, energy centre, car and cycle parking, landscaping and public realm works.

This is the Secretary of State’s decision letter and inspector’s report and this is the Secretary of State’s decision to make a partial award of costs against the Mayor of London, and inspector’s report.

The procedural position here was a little more complicated. After Lewisham had refused this application, the applicant had submitted a further application for planning permission which sought to address the reasons for refusal. The scheme would secure 20.19% affordable housing by habitable room, which the council accepted, on the basis of viability appraisal, was more than the maximum reasonable provision. The Council resolved to approve the application but the Mayor directed refusal, not satisfied that the viability work justified that level of affordable housing.

By that time the first application had been refused and the appellant revised the scheme to reflect the changes introduced into the second application. Accordingly, whilst the appeal was technically against Lewisham’s initial decision on the first application, in reality the only live issues were those raised by the Mayor on affordable housing and viability, including whether a late stage review mechanism was necessary in line with its policy requirement.

I suspect that you needed to be at the inquiry to appreciate the full horror as events unfolded (I wasn’t) but it appears that the viability case against the appellant’s position completely collapsed at the inquiry following exchange of evidence and cross-examination by Russell Harris QC. But that wasn’t the only problem. Presumably to save costs, the council and the Mayor both engaged the same advocate at the inquiry and, once it understood the real position on viability, the council wished to concede various issues but the Mayor was not willing so to do, meaning that the advocate immediately had a conflict of interest and, mid-inquiry, had to recuse herself from acting for the Mayor! The Mayor’s team continued to participate in the inquiry but without challenging the evidence provided by the appellant.

This is from the inspector’s report on the appellant’s costs application:

“On day 2 of the Inquiry, following cross-examination of the Council’s construction costs witness Mr Powling, the advocate representing the Council and the Greater London Authority (GLA) advised that due to a conflict of interest, the GLA would no longer be represented. The GLA however wished to continue with their objections as an unrepresented principal party. Later in the afternoon, following cross-examination by the appellant of Ms Seymour for the GLA, the Council formally withdrew its objections to the proposal on viability grounds. The Council took no further part in the Inquiry.”

“Where the operation of a direction to refuse is issued, the GLA is to be treated as a principal party. Without the GLA direction, the London Borough of Lewisham (LBL) would have granted a planning permission for a now identical scheme. This appeal only arises thus as a result of the change of the resolution to grant to reflect the terms of the GLA’s direction.

6. In its letter to the Inspectorate indicating its intention to attend, the GLA made it clear that was prosecuting its direction in terms and was expecting LBL to do the same. Therefore for all practical legal and policy purposes, the GLA must be treated as a main party prosecuting the terms of its direction at this appeal. Without that direction LBL would not have opposed this scheme and this inquiry would not have been necessary.

7. Their conduct therefore falls to be considered in accordance with the provisions for principal parties.

8. Its conduct was unreasonable in substantive terms in relation to its directed main reason for refusal. Its conduct during the inquiry was also unreasonable. Both levels of unreasonableness resulted in the inquiry and the appellant having to incur significant unnecessary expense in relation to the affordable housing issue.

9. In substantive terms, the GLA produced no evidence which met or came close to the requirements of the PPG on the issue of construction costs to support its reason for refusal.

10. Its ‘evidence” failed to meet the threshold properly to be called “evidence” It failed to engage with the agreed evidence of others that the construction costs were fair and reasonable and during the proceedings failed to read understand or engage with evidence which clearly established that its evidence was incorrect and unreasonable.

11. In terms of the double count issue, the GLA persisted with its case irrespective of evidence suggesting that it was wrong and in an unreasonable fashion after the only other relevant party advised by Leading Counsel had accepted that the point was simply not properly arguable. It chose not to read and understand the clear evidence, notwithstanding it had insisted on the reason for refusal and that it be a party at the inquiry.”

“The Greater London Authority shall pay to MB Homes Lewisham Ltd its partial costs of the inquiry proceedings, limited solely to the unnecessary or wasted expense incurred in respect of the costs of the appeal proceedings related to dealing with the issue of affordable housing after the Council decided not to represent the Greater London Authority, such costs to be taxed in default of agreement as to the amount thereof.”

Oof!

The Secretary’s conclusions on viability were as follows:

“17. The Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that the essential differences on viability between the parties lies in a variation of around £11m in construction costs (including fees and profit); and private residential values (IR127).

Construction costs

18. The Secretary of State notes that CDM (for the GLA) consider build costs to be overstated (IR129). However, the Secretary of State also notes that independent costs estimates produced by 3 firms of costs consultants were within 2 percentage points of each other. He agrees with the Inspector that no evidence has been produced in any later analyses to show that those build costs, or any element of them considered for viability purposes, are unreasonable (IR128-131).

Fees

19. The Secretary of State notes that the level of fees remained a point of difference at the beginning of the Inquiry. The Secretary of State also notes that while detailed analysis of this issue did identify an overstatement of fees of less than £1m, this is far below the overstatement claimed by the Council and GLA. He further notes that, at the Inquiry no evidence was forthcoming from the GLA’s costs witness, CDM, to support their contention that preliminaries are set too high or that the level of professional fees of around 10% would be excessive for a project of this nature. In addition, the Council’s costs witness accepted that if a reasonable preliminaries figure of 17% or so was adopted then the whole argument in support of the £5.5m fees deduction from the overall level of costs fell away (IR132-133).

Profits

20. For the reasons given in IR134-135, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that the proposed profit levels are reasonable for this scheme.

21. For the reasons given in IR136 the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that no evidence was offered by the Council or the GLA to counter the appellant’s build costs analysis or the level of fees or profit.

Private residential values

22. The Secretary of State has carefully considered the Inspector’s analysis in IR137-146 and agrees that the GLA’s suggested values would be unlikely to be achievable in the market (IR144).

23. The Secretary of State also notes that the GLA accepted at the Inquiry that if the £11m alleged surplus on fees and construction costs did not exist, then the claimed remaining £900,000 (IR132) would not have led to a direction to refuse from the Mayor’s office (IR146). For the reasons in IR147, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that the 20.2% affordable housing proposed by the appellant is the maximum, if not somewhat more, than what can be reasonably provided, and he accordingly attaches very considerable weight to this benefit of the proposal. He finds no conflict with the requirements of LonP policy 3.12; the Mayor’s Affordable Housing and Viability SPG, Lewisham CS policy 1 and DMLP policy DM7.

Late stage review

24. For the reasons given in IR148-149, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that there is no pressing case for a late stage review for a scheme such as this, where development is proposed to be completed in a single phase. He finds no conflict with the requirements of LP policy 3.12, the Mayor’s Affordable Housing and Viability SPG, Lewisham CS policy 1 and DMLP policy DM7.”

“In favour, the Secretary of State affords very considerable weight to the provision of market and affordable housing. He also affords moderate weight to the positive contribution to the character and appearance of the emerging Lewisham Town centre.”

And no late stage review!

In amongst the horror show for both the council and the Mayor seems to have been some simple lack of communication as between their witnesses. Quoting from the inspector’s summary of Lewisham’s case:

“When the appellant’s viability proof was received and reviewed it did not appear that the short reference in paragraph 7.2 to the Gardiner & Theobald review report raised any pertinent issue. This was particularly so as the proof suggested that the appellant’s basis for assessment of costs was unaltered.

As a consequence the Council’s viability witness did not send its costs witness the appellant’s viability proof (which dealt with numerous other issues not relevant to costs estimates). On review at the Inquiry, the Council’s build cost estimate was revised from £107,179,737 to £111,809,368 representing a difference of £4,629,631. The consequence of this was that it changed appraisal A – 2018 Residential Pricing to negative £1,155,982 and Appraisal B – 2017 residential pricing (less HPI) reduced to £ 3,111,251. This still represents a £20m disparity approximately with the appellant’s viability conclusions. It nonetheless reduced the margin of surplus on the Council’s assessment to fall within an acceptable margin of error“.

Oof.

Where would we be without the ability properly to test evidence at inquiry?

Simon Ricketts, 25 January 2020

Personal views, et cetera

PS not to be too London-centric, I should add that on the same day the Secretary of State also allowed an appeal for 850 homes near Tewkesbury.

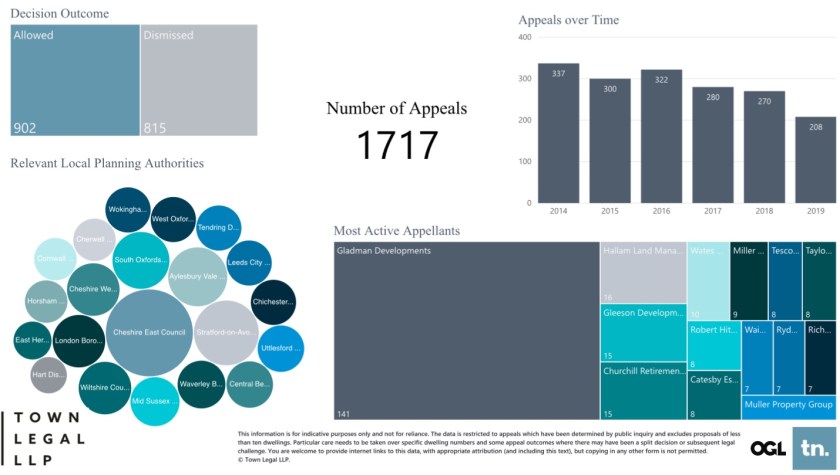

The appeal stats for 2020 are already going to look more healthy than those for the last two years, which become apparent if you interrogate our Town Legal 2014-2019 housing inquiry appeals data visualisation tool.