James Brokenshire’s 13 March 2019 written statement, made alongside the Chancellor’s Spring Statement, includes some important, if sometimes vague, pointers as to how the Government intends to speed up development management processes and housing delivery, although already we have a good sense of what lies ahead in relation to planning appeals that proceed by way of inquiry.

Delivery

My 3 November 2018 blog post covered Sir Oliver Letwin’s recommendations to Government following his review into the “build out of planning permissions into homes“.

The Secretary of State has now confirmed that the Government will “shortly publish additional planning guidance on housing diversification – to further encourage large sites to support a diverse range of housing needs, and help them to build out more quickly“.

He agrees “with the principle that the costs of increased housing diversification should be funded through reductions in residual land values. The Government is committed to improving the effectiveness of the existing mechanisms of land value capture, making them more certain and transparent for all developments. My focus is on evolving the existing system of developer contributions to make them more transparent, efficient and accountable and my department is gathering evidence to explore the case for further reform.”

“I will keep the need for further interventions to support housing diversification and faster build out, including amendments to primary legislation, under review. My department will also work closely with Homes England to identify suitable sites and will look for opportunities to support local authorities to further diversify their large sites.”

Development management

“My priority now is to ensure faster decision-making within the planning system. My department will publish an Accelerated Planning Green Paper later this year that will discuss how greater capacity and capability, performance management and procedural improvements can accelerate the end-to-end planning process. This Paper will also draw on the Rosewell Review, which made recommendations to reduce the time taken to conclude planning appeal inquiries, whilst maintaining the quality of decisions. I will also consider the case for further reforms to the compulsory purchase regime, in line with our manifesto commitment.”

We wait to see what detailed proposals the green paper will include for the planning application stage and indeed for appeals that proceed by way of written representations or hearings.

Bridget Rosewell’s independent review of planning appeal inquiries was published on 12 February 2019. The executive summary sets out the current statistics as follows:

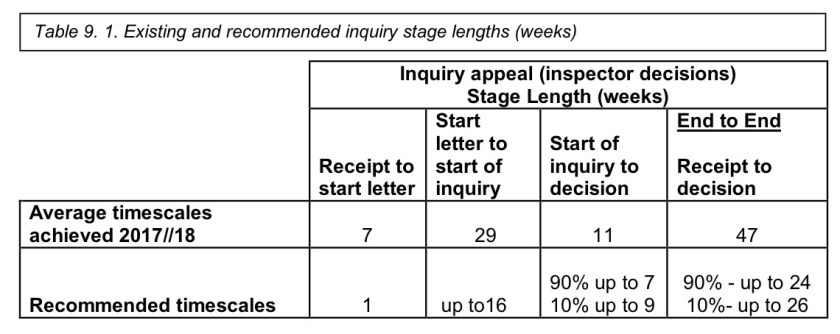

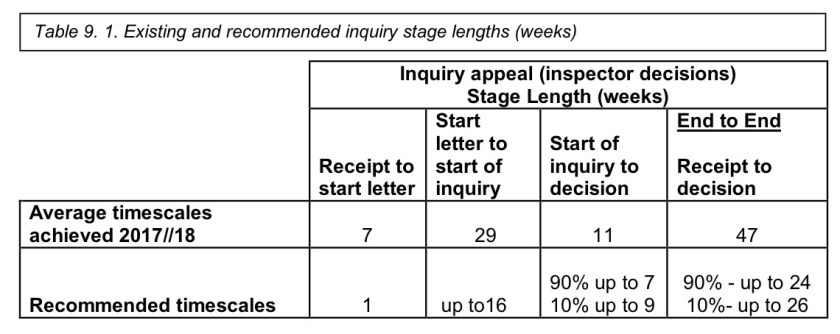

8. “On average, about 315 planning appeals each year are the subject of an inquiry (inquiry appeals), comprising 2% of the total number of planning appeal decisions. Around 81% of inquiry appeals are decided by planning inspectors on behalf of the Secretary State. The remaining 19% of cases (recovered appeals and called-in applications) are decided directly by the Secretary of State, having regard to an inspector’s report.

9. Although relatively small in number the scale of development, particularly housing development, that is determined through inquiry appeals is significant. In 2017/18 over 42,000 residential units were included in inquiry appeal schemes, of which just over 18,600 units were allowed/approved. This represents 5.4% of the 347,000 total approved residential units in the year 2017-18.

10. In 2017/18, it took an average of 47 weeks for inspector-decided cases from receipt of the appeal to a decision letter being issued. On average, it took 60 weeks from the point of validation of an appeal to the submission on an inspector’s report to the Secretary of State for recovered appeals and 50 weeks (from validation to submission of the inspector’s report) for called-in applications. It then took, on average, a further 17 weeks after the inspector’s report had been submitted for the Secretary of State to issue a decision for recovered appeals and a further 26 weeks for called-in applications. In 2017/18, 111 inquiry appeals were withdrawn before a decision was made.”

MHCLG updated its website page Appeals: how long they take on 14 March 2019. That 47 weeks average referred to in paragraph 10 has now slipped to 50 weeks (if that 50 weeks figure excludes recovered appeals and call-ins).

Bridget Rosewell had 22 recommendations as to how the planning appeal inquiry process can be improved and decisions made quickly:

1.The Planning Inspectorate should ensure the introduction of a new online portal for the submission of inquiry appeals by December 2019, with pilot testing to start in May 2019.

2.The Planning Inspectorate should work with representatives of the key sectors involved in drafting statements of case to devise new pro formas for these statements which can then be added to the new portal and include, where appropriate, the introduction of mandatory information fields and word limits.

3.The process of confirming the procedure to be used should be streamlined. Where an inquiry is requested, appellants should notify the local planning authority of their intention to appeal a minimum of 10 working days before the appeal is submitted to the Planning Inspectorate. This notification should be copied to the Inspectorate.

4.The Planning Inspectorate should ensure that only complete appeals can be submitted and ensure that a start letter is issued within 5 working days of the receipt of each inquiry appeal. The start letter should include the name of the inspector who will conduct the appeal.

5.The practice of the Planning Inspectorate leading on the identification of the date for the inquiry should be restored, with all inquiries commencing within 13 to 16 weeks of the start letter.

6.The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) should consult on the merits of appellants contributing towards the accommodation costs of the inquiry.

7.MHCLG and the Planning Inspectorate should substantially overhaul the approach to the preparation of statements of common ground.

8.a) In every inquiry appeal case, there should be case management engagement between the inspector, the main parties, Rule 6 parties and any other parties invited by the inspector, not later than 7 weeks after the start letter.

(b) Following the case management engagement, the inspector should issue clear directions to the parties about the final stages of preparation and how evidence will be examined, no later than 8 weeks after the start letter.

9.The inspector should decide, at the pre-inquiry stage, how best to examine the evidence at the inquiry and should notify the parties of the mechanism by which each topic or area of evidence will be examined, whether by topic organisation, oral evidence and cross-examination, round-table discussions or written statements.

10.The Planning Inspectorate should ensure all documents for an inquiry appeal are published on the new portal, in a single location, at the earliest opportunity following their submission.

11.The Planning Inspectorate should ensure the timely submission of documents. It should also initiate an award of costs where a party has acted unreasonably and caused another party to incur unnecessary or wasted expense.

12.The Planning Inspectorate should amend guidance and the model letter provided for local planning authorities to notify parties of an appeal, to make it clear that those interested parties who want Rule 6 status, should contact the Inspectorate immediately.

13.The Planning Inspectorate should consult with key stakeholder groups, to update its procedural guidance to set out clear expectations on the conduct of inquiries, based on a consistent adoption of current best practice and technology. Updated guidance should encourage and support inspectors in taking a more proactive and directional approach.

14.The Planning Inspectorate should ensure that its programme for improving operational delivery through greater use of technology fully exploits the opportunities available to enhance the efficiency and transparency of the inquiry event, such as the use of transcription technology for inspectors and publishing webcasts of proceedings.

15.Alongside other recommendations that will improve the transparency and clarity of the process (Recommendations 10, 12, 13 and 14), the Planning Inspectorate should develop a more effective and accessible guide to the inquiry process for interested parties, including members of the public.

16.Programming of inspector workloads should ensure there is enough time to write up the case immediately after the close of the inquiry.

17.a) To minimise the number of cases that need to be decided by the Secretary of State, MHCLG should keep their approach to the recovery of appeals and called- in applications under review. b)The Planning Inspectorate should work with MHCLG to identify ways that technology can be used to speed up the process of preparing the inspector’s report to the Secretary of State.

18.The Planning Inspectorate should submit an action plan to the Secretary of State by April 2019. The action plan should set out how it will ensure that the necessary organisational measures are put in place to deliver the proposed timescale targets and wider improvements by no later than June 2020. This should include the mechanisms by which sufficient inspectors can be made available. The action plan should also set out challenging, but realistic, intermediate milestones to be achieved by September 2019.

19.The Planning Inspectorate should review the issue of withdrawn appeals and consider how this impact on its work can be minimised. To deliver this the Inspectorate should:

•(a) always collect information from appellants about why an appeal is withdrawn

•(b) initiate an award of costs where there is evidence of unreasonable behaviour by a party in connection with a withdrawn appeal

•(c) with the benefit of more detailed information, review whether further steps can be taken to reduce the impact of withdrawals on its resources and other parties.

20.The Planning Inspectorate and MHCLG should regularly discuss the practical impact of new policy and guidance on the consideration of evidence at inquiries, with those parties who are frequently involved in the planning appeal inquiry process.

21.The Planning Inspectorate should adopt the following targets for the effective management of inquiry appeals from receipt to decision

(a) Inquiry appeals decided by the inspector

Receipt to decision – within 24 weeks – 90% of cases Receipt to decision – within 26 weeks – remaining 10% of cases

(b) Inquiry appeals decided by the Secretary of State

Receipt to submission of inspector’s report – within 30 weeks – 100% of cases

22.The Inspectorate should regularly report on its performance in meeting these timescales and what steps it is taking to expedite any cases that take longer.

•(a) The Planning Inspectorate should use its Transformation Programme to ensure there is robust and comprehensive management and business information, which is regularly collected and reported, on all aspects of their operation.

•(b) In developing an improved suite of information the Inspectorate should also:

•ensure their digital case management record system records information on key variables in a consistent way

•agree with MHCLG a new set of key performance indicators to effectively monitor the inquiry appeal process from end to end, including the availability of senior inspectors. “

These tables give a sense of what we might expect:

The Planning Inspectorate announced on 13 March 2019 that it is carrying out a trial of accelerating a small number of inquiry appeals as part of a pilot of holding inquiries much earlier than at present. For these appeals it will move away from its “bespoke” process whereby PINS invites the parties to agree a programme, including an inquiry date.

Before long we will all have to adapt our approaches to individual appeals in the interests of a more generally speedy process. It will be increasingly difficult to seek to negotiate a later date than PINS proposes (even when the main parties have no objections) in order to accommodate particular team members’ availability.

For the Inspectorate, it’s certainly going to be a period of change. It was announced today, 15 March 2019, that Graham Stallwood, currently chief planning officer at the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and chairman of the board of trustees of the RTPI, has accepted a position as PINS’ Director of Operations, commencing in May. Graham – you will be excellent!

For those of us who lodge and coordinate appeals for developer clients, well we are going to need to get to grips with a new IT interface for the submission of appeals and new case management processes but above all find the strength to tell our clients the news that, having been at the heart of strategic thinking in relation to a decision to invest in an appeal and having shaped the statement of case, their favourite QC may not in fact be available for that crucial inquiry…

Simon Ricketts, 15 March 2019

Personal views, et cetera

Speedy Delivery, Richland, Washington, MA