On 4 November 2024 the New Towns Taskforce published its call for evidence with a deadline of 13 December 2024.

I live near an existing new town: Hemel Hempstead. This morning I happened to come across this 12 minutes promotional film from 1957, pitching its virtues to potential residents and workers, sponsored by furniture company Dexion which was building a factory as part of the new town project. The film is well worth a view. Who wouldn’t want to live in a place like this, I thought – a fresh start, cleanliness, space, facilities, modernity. Much of it is still recognisable to me. The Hemel Homestead dream portrayed in the film certainly hasn’t died, although it’s fair to say that some of those facilities may not still be there, or are much degraded, with an increasing lack of secure funding streams or the ravages of the market economy. And we have seen the replacement of that rather centralised post-war command and control economy, where so many people seemed to accept, whether or not under sufferance) their rigid place in society, with our so much more diverse and individualistic 21st century neo-liberalism.

(The film is on the BFI “Britain on Film” website. Just put in your postcode into this map and you will have access to many digitised amateur home movies, documentaries and news footage dating back more than 100 years).

Those planning the next generation of new towns would do well to reflect on lessons learned from previous generations. The post-war new towns programme saw 27 UK new towns built by state-sponsored development corporations under the New Towns Act 1946 and later amending legislation. One of the conundrums that successive governments have grappled with over the last 45 years or so is how to create the conditions in which the private sector, rather than the state, can bring forward and deliver residential-led proposals at scale, whether in the form of new towns or urban extensions.

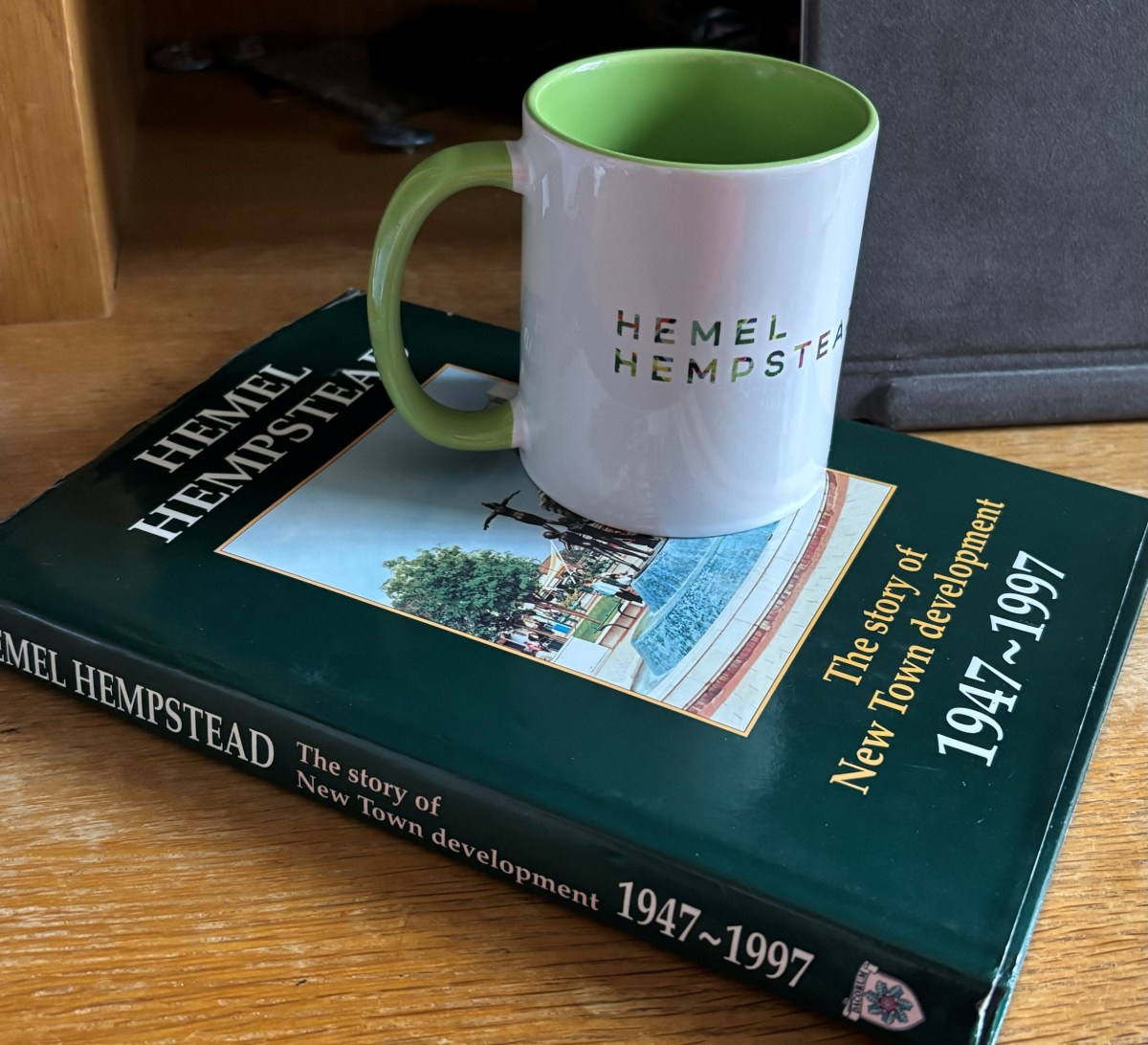

Watching that film caused me to turn back to a book I have: Hemel Hempstead: The Story of New Town Development 1947-1997. One of its lessons for government may not be a popular one: expect resistance. Local activism against change, even resort to litigation to seek to prevent development, is certainly nothing new.

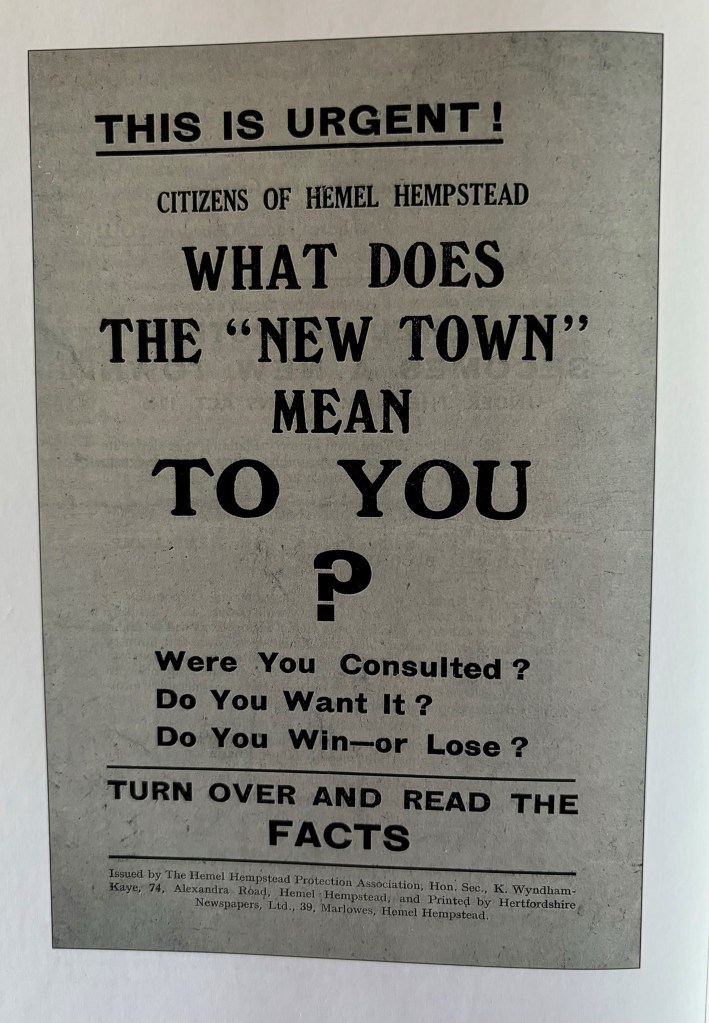

The book recounts a public meeting in 1946 at which the minister, Lewis Silkin, sought to justify the proposals. 150 local people turned up, sceptical of the project, expressing concerns as to “just how many undesirables” would move here from London (that would be me then), as to the prospect of demolition of older properties and loss of agricultural land. There was then a public inquiry which lasted all of three days! The Hemel Hempstead Protection Association sought to challenge the conclusions of the inquiry in the High Court on the basis that there had been inadequate consultation with the relevant local authorities but was rejected on 30 July 1947. I can’t find the judgment but the book asserts that it contains the sentence: “It may well mean that the village of Hemel Hempstead must die in order that Great London may live“. I’m not sure about that…

(Poster as reprinted in the book mentioned above, published in 1997 by Dacorum Borough Council)

In turn all of this sparks memories of the more well-known protests against Stevenage new town, recounted for instance in 2022 by Stephen V. Ward ‘An essay in civilisation’? – Stevenage and the post-war New Towns programme (note indeed that celebrities had their role, even back than…):

“In contrast to this expert planning process quietly taking place within the Ministry, local anxieties had been growing since the Abercrombie plan’s first intimation of a satellite town (Cullingworth 1979: 27-31). The awareness from late 1945 that Abercrombie’s proposals were beginning to be acted upon heightened the unease. The Stephenson plan was not, of course, prepared in secret. A few team members had visited the area and there had been meetings with local officials but no formal contact with either the community or elected members of Stevenage Urban District Council. Meanwhile events moved on and opinions hardened. By February 1946, local development applications were being refused because they contravened the still undisclosed New Town plan. Then, in April, the famous novelist E. M. Forster condemned on radio the new ‘meteorite town’ set to land on Stevenage, where his novel Howard’s End had been set (Forster 1965: 68).

Only when the plan was virtually complete, later in April, did the planners and Ministry officials finally meet local councillors to explain it (TNA, HLG 91/74. Beaufoy, Memo, 27.4.1946). But already compulsory purchase notices were landing on Stevenage doormats. Most affected houses were only recently built but located within what would be the northern part of the proposed industrial zone. It meant, bizarrely, that the first specific thing local people learned about the New Town was that, despite a severe national housing shortage, perfectly fit houses would be demolished. (Over time, the industrial zone was reduced in size and these same houses are still there today.) The meeting with the council occurred in an atmosphere of what a ministry official optimistically termed ‘polite antagonism’. A few days later, on 6th May, all hell broke loose (TNA, HLG 91/77). During that day Lewis Silkin visited the town, meeting local people, the council and finally addressing an evening public meeting. Seemingly oblivious of what was brewing, the Minister confidently expected to carry the day. He had already arranged a triumphant news story ‘A New Town is Born’ to be circulated to the world’s press. Others had more accurately foreseen events. On 30th April, the London Evening News led with the headline ‘Doomtown Protest Rising’. The following day the Stevenage Residents’ Protection Association was formed and its membership and funding quickly grew.

At the public meeting (see Figure 2) over 350 people filled Stevenage Town Hall with (in some reports) about half the local population outside, listening on loudspeakers. The strongest objections came from farmers and residents set to lose their livelihoods or homes. There were also many general concerns: that Stevenage was the victim of a national experiment, that history was being uprooted and everything was being done in dictatorial fashion. Despite some cheers, the meeting did not go well for the Minister, his speech frequently being interrupted. He appealed to the audience’s highest instincts and invoked the wartime spirit. Yet such arguments did not assuage protesters who thought him profoundly anti-democratic, with cries of ‘hark, hark, the dictator’ and ‘Gestapo’. Nevertheless, Silkin assured incredulous listeners that soon ‘[p]eople from all over the world will come to Stevenage to see how we here in this country are building for the new way of life.’ He left the hall to find a tyre of his official car had been deflated and (it was suspected) sugar put in the petrol tank.”

(This was the famous incident where of course signs at Stevenage railway station were switched for signs reading “Silkingrad”. See also the litigation brought by those opposing the development, culminating in Franklin v the Minister of Town and Country Planning (House of Lords, 1948).

As was the case in the late 1940s, so now – the government should expect equivalent tests of its resolve. Where would we be if those planning Hemel Hempstead, or Stevenage, or other new towns of the time, had caved? A study of the anti-new towns campaigns and litigation of that time would be an informative read.

Simon Ricketts, 17 November 2024

Personal views, et cetera

Excellent, well researched and presented piece, thank you. Carefully planned New Towns should form a significant plank of our housing strategy and there is much to commend Hemel and the other 40s New Towns in terms of their concept even if the execution my not have been to 2024 master planning standards. Much progress has been made in this area and the next raft of New Towns will be better.

Funding them from private investment will be more challenging. Incetives will be needed that can also be passed on to buyers and tenants. Maybe investors/ developers could bid for preference shares in a new form of development company that had CPO powers, subject to a 10-year bonus dividend payable to vendors and displaced households.

This will need careful design and planning…

LikeLike

Many thanks and agreed.

LikeLike