“If we are doing things in parallel, it does mean when we get towards the summer we can make sure these things are knitting together properly and actually bring them together, with those pieces of the jigsaw starting to come together as one whole piece—hopefully, one whole beautiful piece as well” – Brandon Lewis, then minister for housing and planning, 24 February 2016, in evidence to the Commons CLG Select Committee – responding to concerns as to the various changes to the planning system then (and still) underway, including proposed changes to the NPPF, LPEG review and the Housing and Planning Bill (now an Act but still inchoate). (And he was referring to summer 2016…)

Of course a few other things happened to knock summer 2016 off course. But still we wait for the full picture and hence the growing frustration over continued delays to the Housing White Paper and speculation as to its contents.

“OK, that’s politics”, we may say, but is there a more fundamental, longterm, problem to be tackled?

“[M]inisters cannot frustrate the purpose of a statute or a statutory provision, for example by emptying it of content or preventing its effectual operation” (Supreme Court in R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union 24 January 2017, para 51).

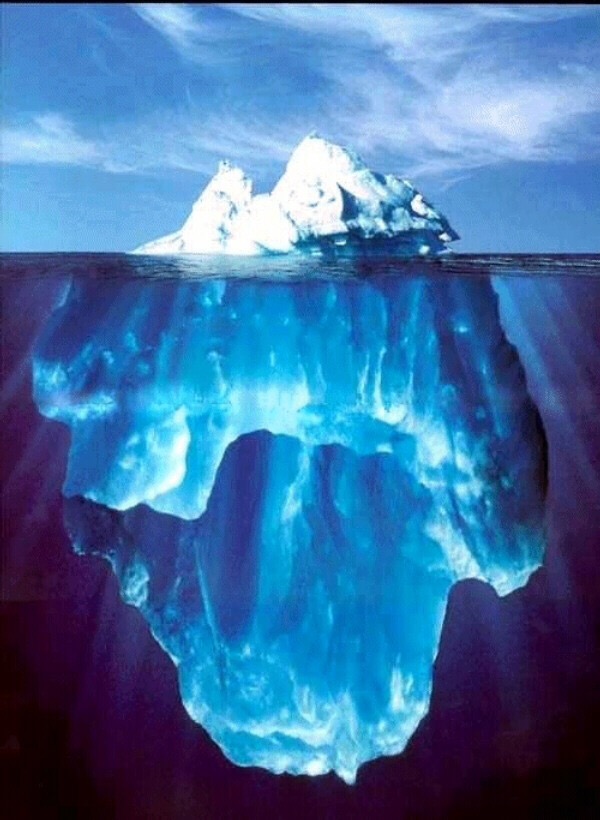

On reading this, it struck me that there is a logical disconnect at the heart of the modern planning system. Section 38(6) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 requires that decisions be taken in accordance with the statutory development plan “unless material considerations indicate otherwise”. However, the Government’s non-statutory NPPF, despite an amorphous status as a “material consideration”, somehow often ends up trumping the statutory plan (for example – currently – by way of para 49 deeming policies for the supply of housing to be regarded as out of date in defined circumstances, triggering the para 14 presumption and – under the changes consulted upon last year – by way of the proposed housing delivery test). From where does the NPPF gain its authority in our statutory plan-led system? What is to prevent an LPA from deciding to give its policies little weight and how does the resultant uncertainty help anyone?

The Court of Appeal in Suffolk Coastal District Council v Hopkins Homes, Richborough Estates v Cheshire East Borough Council (Court of Appeal, 16 March 2016) set out the position as follows:

“The NPPF is a policy document. It ought not to be treated as if it had the force of statute. It does not, and could not, displace the statutory “presumption in favour of the development plan”, as Lord Hope described it in City of Edinburgh Council v Secretary of State for Scotland [1997] 1 W.L.R. 1447 at 1450B-G). Under section 70(2) of the 1990 Act and section 38(6) of the 2004 Act, government policy in the NPPF is a material consideration external to the development plan. Policies in the NPPF, including those relating to the “presumption in favour of sustainable development”, do not modify the statutory framework for the making of decisions on applications for planning permission. They operate within that framework – as the NPPF itself acknowledges, for example, in paragraph 12 (see paragraph 12 above). It is for the decision-maker to decide what weight should be given to NPPF policies in so far as they are relevant to the proposal. Because this is government policy, it is likely always to merit significant weight. But the court will not intervene unless the weight given to it by the decision-maker can be said to be unreasonable in the Wednesbury sense”.

Whilst the statutory role of government guidance is clear in relation to plan-making (section 19 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 provides that “in preparing a local development document the local planning authority must have regard to…national policies and advice contained in guidance issued by the Secretary of State”) there is no such statutory signposting in relation to decision-making.

It didn’t have to be this way. Consideration was indeed given to giving the NPPF statutory status as the Localism Act went through Parliament. The then minister of state for decentralisation Greg Clark stated in Public Bill Committee on 15 February 2011:

“There are some suggestions that a reference to the significance of the NPPF would be helpful. Against that, however, I have heard some concerns in our discussions that link to the points made by the right hon. Gentleman the Member for Greenwich and Woolwich about not taking a year zero approach to things and completely designing the system from scratch. One of the features of the present regime with which the right hon. Gentleman is familiar is the importance of section 38(6) of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004. That provision establishes the primacy of the development plan, which obviously needs to be consistent with national policy. If we were to establish in the Bill a new primacy for national policy that is different from how we have managed in recent decades, I would want to be cautious that we did not introduce something, albeit with the best of intentions, that changed the accepted understanding of the importance of the primacy of the development plan and that, in effect, interferes with section 38(6) without good purpose. If there is a balance of advantage in the approach, I think we can contemplate it, but it behoves us to reflect carefully on the representations that have been made, which I undertake to do.”

Scotland’s National Planning Framework has statutory effect pursuant to section 1 of the Planning etc (Scotland) Act 2006.

In relation to infrastructure, we of course have a statutory regime of national policy statements to set the framework for decisions in relation to development consent orders, with ten NPSs having been prepared so far pursuant to section 5 of the Planning Act 2008.

In contrast to these regimes, the NPPF can be amended with little Parliamentary scrutiny.

The position is even worse in relation to written ministerial statements on planning policy matters, when one recalls, for example:

– Eric Pickles’ 20 May 2010 statement that the then intended abolition of regional strategies was to be a material planning consideration in decision-making, which led to Cala Homes (South) Limited v Secretary of State (Court of Appeal, 27 May 2011). The court concluded that “…it would not be safe for the Court to assume that at this stage there are no circumstances in which any decision-maker could rationally give some weight to the proposed abolition of regional strategies. In view of the uncertainty created by the legal obstacles…[the need for Parliamentary process to be undergone and SEA]… and any decision-maker who does think it appropriate to give some weight to the Government’s proposal when determining an application or an appeal would be well-advised to give very clear and cogent reasons for reaching that conclusion, but that does not mean that there could be no case whatsoever in which any decision-maker might be able to give such reasons.”

– Eric Pickles’ 28 November 2014 statement introducing the vacant building credit and small sites affordable housing threshold, which led to West Berkshire Council v Secretary of State (Court of Appeal, 11 May 2016). Despite the absolute wording of the statement, it was interpreted by the court as necessarily admitting of exceptions, leading now to a mess of conflicting appeal decisions by inspectors, well documented by Planning magazine (27 January 2017 issue).

– Gavin Barwell’s 12 December 2016 statement amending (without prior consultation) the five year housing land supply threshold in para 49 of the NPPF, which has recently led to a judicial review being brought by a group of no fewer than 25 housebuilders and developers.

Brandon Lewis’ statement at the outset of this post is quoted in the Commons CLG Select Committee’s review of consultation on national planning policy published on 1 April 2016. The Committee responded to his optimism as follows:

“We welcome the Minister’s indication that any changes to the NPPF resulting from this consultation will be made during summer 2016, and that he intends to draw together the outcomes of the consultation with those of the other changes affecting the sector“.

The Committee’s formal recommendations included:

“As a priority the Department should publish clear timescales for the next steps for this consultation, including timescales for the Government’s response, implementation, and suitable transitional arrangements. If the changes to the NPPF are delayed beyond summer 2016, we expect the Minister to write to us to explain the reasons and provide updated timescales”

” As a matter of principle, we believe that when changes are made to the wording of a key policy framework such as the NPPF, there should be a two-stage consultation process: first on the overall policy, and subsequently on the precise wording which will give effect to the change. If there is no further consultation on the specific wording of the consultation proposals, it is essential that the Department listens carefully to concerns about ambiguity or lack of clarity in the revised NPPF, and provides clarification where required”

“To ensure that proper consideration is given to the impact of changes resulting from this consultation, and from other developments in the housing and planning sector, the Department should carry out a comprehensive review of the operation of the NPPF before the end of this Parliament. The review must include sufficient opportunity for appropriate consultation with stakeholders, and should follow a two-stage approach to consulting, first on general principles, and subsequently on precise wording.”

All sensible, but what a waste of energy. Nine months after the report there has been no Government response!

How are decision-makers meant to balance non-statutory, unstructured interventions from ministers with the outcomes pointed to by statutory planning policies? This surely a very difficult task for decision-makers and with the constant risk of unwelcome surprises for those at the sharp end. Personally, I would go further than the Select Committee’s recommendations and instil basic, legally binding, procedural discipline into ministers’ approach to policy making, given the risk that the statutory planning system is otherwise frustrated, emptied of content or prevented from effective operation (to use the words of the Supreme Court).

Simon Ricketts 28.1.17

Personal views, et cetera