You need to know how the rules are changing from 1 April 2026 for 94.7% of planning appeals: those that proceed by way of written representations. There are traps for the unwary: whether for appellant, local planning authority or third party.

The changes have been on the cards since last June – see my 28 June 2025 blog post How Do You Solve A Problem Like…Speeding Up Planning Appeals Without Being Unfair Or Counter Productive?

On 12 February 2026 the Planning Inspectorate published Planning appeals: procedural guide. For appeals relating to applications dated on or after 1 April 2026 alongside the Town and Country Planning (Appeals) (Written Representations Procedure) (England) (Amendment and Saving Provision) Regulations 2026 which were laid before Parliament that day.

The main difference is that the “expedited” or “part 1” written representations procedure, which currently applies in relation to householder and minor commercial appeals, will be extended to most appeals to be determined by way of written representations, resulting from applications made from 1 April onwards.

Under the procedure, the appellant is not able to submit evidence at appeal not previously considered by the LPA when they determined the application, leaving the appeal to be determined by the inspector solely by reference to:

- the application that the LPA determined (including all supporting evidence, plans and interested party comments)

- the LPA’s decision notice (including their reasons for refusal where applicable)

- The LPA’s committee minutes and planning officer report

- The appeal form

- The LPA’s appeal questionnaire

Third parties are not able to make further representations at the appeal stage so will have to rely on the inspector taking into account any representations that were made during the course of the application.

As is already the case with all written representations appeals (part 1 or part 2), if a section 106 agreement or unilateral undertaking is required, the completed (i.e. executed and dated) version needs to be submitted at the time the appeal is submitted.

This part 1 procedure will apply to the following types of appeal:

- Appeals against a refusal of planning permission

- Appeals against a grant of planning permission subject to conditions that the applicant objects to

- Appeals against a refusal of prior approval

- Appeals against a refusal of advertisement consent

- Appeals against the refusal of an application to approve a reserved matter

- Appeals against the LPA’s refusal of an application to modify or remove a condition under section 73 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990

- Appeals against the LPA’s refusal of an application for planning permission for development already carried out under section 73A of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990

- Appeals against permission in principle or refusal of technical details consent

It is open to the Planning Inspectorate to decide that that an appeal which is eligible to follow the part 1 procedure should instead follow a different procedure. For example the guidance says that “appeals against an LPA’s refusal of a biodiversity gain plan, whilst eligible to proceed under part 1, will usually follow the part 2 procedure”.

This leaves only the following types of written representations appeal as still following the existing part 2 procedure:

- Appeals against the LPA’s failure to determine an application within their time limit for doing so (‘non-determination’ cases)

- Appeals in relation to an application for Listed Building Consent

- Appeals in relation to a discontinuance notice

Why the changes? The most useful, detailed, justification for the changes is set out in the explanatory memorandum to the Regulations. It states that as at March 2025, appeals following the part 2 procedure took an average of 29 weeks whereas appeals following the part 1 procedure took an average of 18 weeks. (In fact the Planning Inspectorate’s December 2025 figures show improvements on these timescales, the averages now being 21 and 14 weeks respectively – with hearings taking an average of 25 weeks and inquiries an average of 38 weeks).

The memorandum says this:

“The number of appeals decided through both written representations procedures will remain the same. Expanding the expedited procedure will allow more appeals to be decided more quickly. It will reduce pressure on local planning authorities by removing the need for them to submit a full statement of case, although they will need to ensure that the decision notice or officer’s report is sufficiently detailed. Additionally, with no further opportunity to comment, it removes the need to process and publish representations from interested parties. It will reduce the burden on appellants by reducing the amount of documentation needed when submitting an appeal. It will reduce the burden on all parties by removing the opportunity for any comments at the appeal stage. By expanding the expedited written representations appeal procedure to a broader range of appeals, larger developments will also benefit from the streamlined process and quicker decisions, helping to unlock economic growth and accelerate the delivery of homes.”

Taking this at face value, obviously quicker decision times are in everyone’s interests.

However, certainly there are concerns:

- Whilst it is said that the number of appeals decided by way of written representations will remain the same, is this the slippery slope and will we see over time a greater overall proportion of appeals going by this route, including a greater proportion where the complexity of issues and level of potential third party interest makes the process appear like an inappropriately summary form of justice?

- What happens in the frequent case where the appellant requests a hearing or inquiry route but is pushed down the written representations route by the Planning Inspectorate (given that the criteria for which appeals are appropriate for written representations, hearings and inquiries are not objective but rely on the application of judgment in each particular case)? The procedural switch is already problematic but will get more difficult.

- What about where members refuse an application against officers’ advice? Perhaps helpfully for appellants, in practice the basis for the members’ decision will have to rest on the minutes of the committee meeting. In practice will this mean a greater number of deferrals so that credible potential reasons for refusal can be prepared?

- Do the changes favour well-advised potential appellants? The strategy is now clear: the applicant needs to make sure that their application package is robust and appeal-ready, that they have responded to issues raised by third parties and they have resolved or narrowed down any potential difference in relation to any necessary section 106 agreement or undertaking – and to have made good progress on a draft.

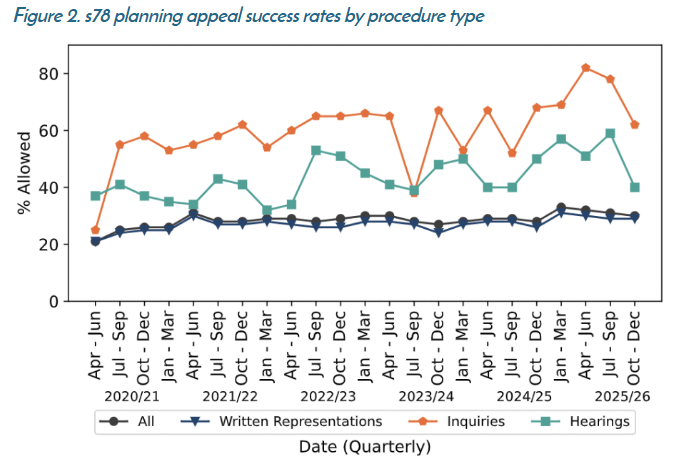

Lastly, perhaps a few words on the statistics as to which procedure is most likely to result in an appeal being allowed. Appeal Finder have done some good statistical analysis.

Whilst this shows that by comparison of appeal route, inquiries are most likely to succeed, followed by hearings – and with the written representations procedure being least fruitful for appellants, I am always cautious as to the conclusions to be drawn. It is tempting to think that the obvious strategy is to seek an inquiry and, failing that, a hearing – and lawyers like me will usually trot out the benefits of cross-examination and formal exchange of evidence (inquiries), the greater likelihood of a senior inspector being appointed and at the very least the opportunity to tell from the inspector’s body language and line of questioning whether he or she has understood the particular issues. Much of this is true. But to what extent are the statistical differences simply correlation rather than causation? Surely the larger the scheme the better professional advice the applicant is likely to have had and the less likely the applicant is to contemplate taking to appeal a proposal that is doomed to fail? I wonder if there is any housebuilder that has collected statistics on their own projects as to whether there is a material difference in outcomes for projects with an equivalent project team involved?

In the meantime, if you have an application on the stocks where a written representations appeal may ultimately be required, don’t get caught out come 1 April….

Simon Ricketts, 15 February 2026

Personal views, et cetera