Congratulations Sir Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London, and Christopher Katkowski CBE KC on your respective new year’s honours.

CK CBE KC of course led work on a report published in January 2024 for the last government which considered any changes to the London Plan which might facilitate housing delivery on brownfield sites in London. The report lays bare the undersupply of new homes in London, which has not kept pace with increases in jobs, population and housing demand.

Sir SK’s Greater London Authority published on 19 December 2024 Accelerating Housing Delivery: Planning and Housing Practice Note. I summarise the document later in this post and would welcome reactions as to whether the document – non-statutory, intended as practical guidance and a material consideration in the determination of planning applications and, in part, renegotiation of existing section 106 agreements – really goes far enough, given where we currently are.

The need for additional housing in London, at all price points, both subsidised (“affordable”) housing and general market housing, has never been more acute. It is in fact much worse now than when CK CBE KC wrote that report. The statistics back that up, with planning approvals and housing starts both down sharply last year.

Annual housing completions have been falling short of the policy target in the 2021 London Plan of 522,870 net housing completions from (2019/20 -2028/29). Everyone knows that the viability position for developers is increasingly difficult, faced with build cost inflation, high interest rates and the costs and uncertainty of, for example, additional building safety requirements. Similarly everyone knows that there is an absence of registered providers willing to take on the affordable housing, leading to stalled schemes (a national problem – see the HBF’s December 2024 press statement 17,000 Affordable Homes stalled by lack of bids from Housing Associations and accompanying report).

We have the London Plan’s 50% affordable housing requirement – and with a relatively rigid and formulaic system of early stage and late stage viability review mechanisms where that cannot be met (the late stage review not being required where the “fast track” applies, i.e. if the developer commits to at least 35% affordable housing – 50% on industrial or public sector land), all in accordance with London Plan Guidance on affordable housing and on development viability which have remained in draft since May 2023.

Before we look at the practice note, let’s see what some of the evidence is saying, for instance the GLA’s own November 2024 document, Housing in London 2024: The evidence base for the London Housing Strategy (the charts referred to are here):

“London is home to both the fastest and slowest-growing local housing stocks in England. The number of homes in Kensington and Chelsea grew by 2% over the last decade, compared to 26% in Tower Hamlets (chart 2.1). Using data on new Energy Performance Certificates to track completions of new homes, it looks like new supply in 2024 is following the trend of 2022 and 2023, two of the lowest years in the last five years (chart 2.2).

The quarterly number of planning approvals is falling, and they are concentrated on fewer, larger sites (chart 2.4). Increasing construction on small sites might be key to increasing overall delivery, with 65,000 new build homes completed on small sites between 2012/ 13 and 2021/ 22 (chart 2.3). Sales of new market homes in London peaked in 2022 and then fell considerably, partly due to lower demand from Build to Rent (BTR) providers and the end of Help to Buy (chart 2.6). The BTR sector, which completed 44,585 new homes in London between 2009 and 2023 is nevertheless still growing (chart 2.7).

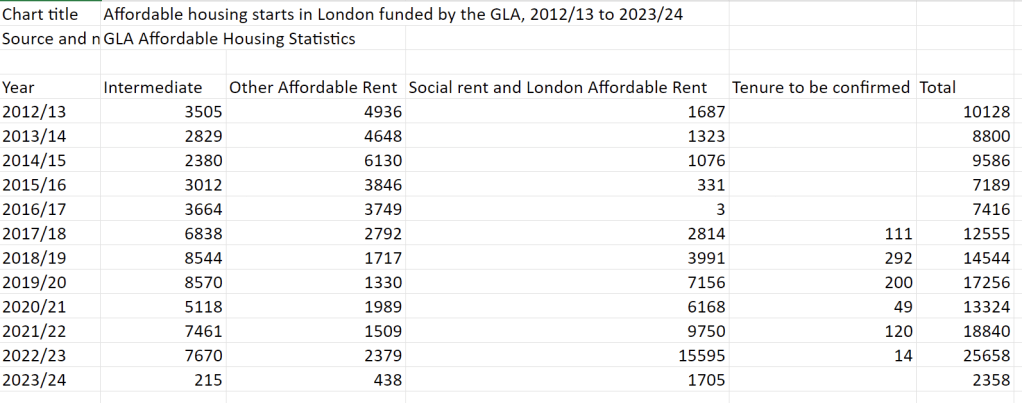

38% of homes and 46% of habitable rooms recommended for approval by the Mayor in 2023 were affordable, with both of these figures a record high (chart 2.5). Affordable housing starts funded by the GLA fell sharply between 2022/ 23 and 2023/ 24 (charts 2.8 and 2.9), as registered providers and local authorities have diverted resources away from new supply in response to increased remediation and refurbishment costs and the costs of adapting to changing regulations. Completions are also down, but not as much. Of the affordable homes started with GLA support in 2023/ 24, 72% were for social rent. Affordable completions from all funding sources also rose to a recent high of 15,768 in 2022/ 23 (chart 2.10), with data for 2023/ 24 not yet available.

Social housing landlords in London owned just under 800,000 affordable homes for rent in 2023, the highest total since 2002 (chart 2.12). Sales of council homes through the Right to Buy (RTB) scheme have been on a downward trend since their peak in the 1980s, totalling 1,080 in 2023/ 24 (chart 2.11).

Council tax data showed that 2.3% of homes in London were empty in 2023, with only 1% empty longer than 6 months (chart 2.13). These are much lower levels than in the 1980s and 90s, when around 5% of homes used to be empty.

1.34 million homes in London, or 36% of its stock were leasehold homes in 2022/ 23, over half of which were privately rented (chart 2.15). In 2023, there were 22,770 homes in multiple occupation (HMOs) with mandatory licences in London. This is the highest of any region (chart 2.14).”

This is chart 2.8 referred to in that text:

This is an extract from chart 2.4, showing the annualised trend per quarter in the number of new homes approved, and the number of projects:

Ahead of the awaited review of the London Plan, what can be done? The sorts of specific, practical, issues that currently come up again and again relate to the operation of the viability review mechanisms in particular. Since the new Building Safety Act regime came into force on 1 October 2023 the early stage review mechanism, kicking in if substantial implementation (usually defined as construction of the foundations and ground or first floor) hasn’t taken place within two years of permission, is increasingly unworkable for higher-risk buildings given how long the gateway two stage is taking in practice. The contingent liability that the late stage review mechanism represents is unattractive in principle to funders, which is a big challenge in a weak market.

For measures that could have had an immediate positive impact, what about, for instance, introducing suitable flexibility into the triggering of the early stage review? Potentially a temporary “holiday” from the late stage review for schemes that committed to proceed to completion within an agreed timescale? A willingness to accept renegotiation of section 106 agreements on schemes which are now unviable? Some pragmatism as to commuted payments towards off-site delivery where a registered provider cannot be found?

Whilst the document does include some measures which may help at the margins, there’s certainly no “big bang” of that nature. It is in fact curious how little fanfare the practice note has been given. I can’t even find it on the GLA website, let alone any press release. Nor was any formal consultation or indeed feedback invited.

Anthony Lee at BNP Paribas did this good summary on LinkedIn before Christmas but I have seen little else.

I draw out some of the measures as follows:

- Allowing the fast track threshold to be reduced, both for new and current applications and also for consented schemes, where the tenure split provides proportionately more social rent than the policy requirement, in accordance with a formula that appears to seek to avoid any financial advantage to the developer in so doing – the only advantage being if that unlocks more GLA funding and/or more willingness on the part of registered providers.

- Estate regeneration schemes will be able to qualify for the “fast track” if at least 50% of the additional housing will be delivered as affordable.

- The GLA will consider accepting supported housing and accommodation for homeless households, with nomination rights for the relevant borough, as a like for like alternative for intermediate housing, again both for new and current applications and also for consented schemes.

- The cost of any meanwhile accommodation for homeless households, with nomination rights given to the relevant borough, may be taken into account in the operation of viability review mechanisms.

- With the late stage review, the developer currently retains 40% of any surplus profit. In certain circumstances this can now increase to 70%. However, the criteria are tight. “To qualify for this, the application must provide at least 25 per cent onsite affordable housing by habitable room for schemes with a 35 per cent threshold, and 35 per cent onsite for schemes with a 50 per cent threshold, at the relevant local plan tenure split, and be certified as reaching practical completion within three years of the date of this document.” “For larger phased schemes that provide at least 25 per cent affordable housing across the scheme as a whole that are granted planning permission after the date of this practice note, if the initial or a subsequent phase is certified as reaching practical completion within three years of the date of this document, the GLA will consider allowing the applicant to retain 70 per cent of any surplus profit identified in that phase when the late review is undertaken. The relevant phase must include at least 100 residential units.”

- There is this enigmatic sentence: “The GLA will also work with boroughs to identify sites that have been allocated for development or that have been granted consent but that have not come forward for development for many years, or where limited progress has been made, and will assess the nature of interventions required to facilitate this.”

- Great flexibility is announced as to the permissible inputs into review mechanisms. The formulae currently focus on changes in gross development value and build costs. “However, in some cases it may be more appropriate to allow for a full viability review to be undertaken which reconsiders all development values and a greater scope of development costs, including professional fees and finance costs.”

- The Mayor’s housing design guidance should not be applied mechanistically, in relation to, for instance, the reference to the need to submit “fully furnished internal floorplans” and the objective that new homes should be dual aspect.

- Various grant funding measures but I’ll look to others to comment as to the extent they will move the dial.

Thoughts?

Simon Ricketts, 11 January 2025

Personal views, et cetera