The planning system doesn’t just fail to provide homes. There are clear lessons to be learned from the unstructured and inadequate approach that successive governments have applied to securing appropriate strategic rail freight interchange developments (SRFIs, in the jargon) to serve London and the south east. That approach has now wasted decades without a spade in the ground, despite millions of pounds having been spent, countless inquiries and High Court proceedings and no doubt a lifetime of worry for those potentially affected. The difficulties with SRFIs also illustrate that the problems aren’t over even when planning consent is obtained – issues of commercial viability and land control are as fundamental.

This blog post summarises where the three leading contenders have reached: Goodman’s Colnbrook Slough scheme, Helioslough’s former Radlett Aerodrome scheme and Roxhill’s Howbury Park scheme, all in the green belt. It is a long story but that’s why I have tried to tell it.

What is an SRFI?

An SFRI is defined in the Government’s National Networks national policy statement January 2015 as a “large multi-purpose rail freight interchange and distribution centre linked into both the rail and trunk road system. It has rail-served warehousing and container handling facilities and may also include manufacturing and processing activities”.

What is the consenting process?

If the proposal falls within the criteria in section 26 of the Planning Act 2008 (eg a site area of at least 60 hectares, to be connected to national rail network and capable of handling (a) consignments of goods from more than one consignor and to more than one consignee, and (b) at least four goods trains a day), it falls under the NSIP procedure.

The only SRFIs so far consented as NSIPs have been Prologis’ Daventry International Rail Freight Terminal (3 July 2014) and Roxhill’s East Midlands Gateway Rail Freight Interchange (12 January 2016) (the latter against the examining authority’s recommendations). Goodman’s East Midlands Intermodal Park, Roxhill’s Northampton Gateway Rail Freight Interchange, Ashfield Land’s Rail Central Strategic Rail Freight Interchange (also Northampton) and Four Ashes’ West Midlands Interchange are all at pre-application stage.

An NSIP can of course include associated development. There can be uncertainties as to the extent of warehousing that is justified and the degree to which commitments are to be given as to its rail-connectedness. For applications made from 6 April 2017, up to around 500 homes may also be included (see section 160 of the Housing and Planning Act 2016 and the Government’s March 2017 guidance).

If the proposal doesn’t meet the NSIP criteria, it will need to proceed by way of a traditional planning application. The NSIP process has its pros and cons. It is interesting to note that the three schemes we will be looking at in this blog post have been proceeding by way of a planning application, with the site areas of the Colnbrook and Howbury Park schemes being 58.7 hectares and 57.4 hectares respectively (given an NSIP threshold of 60 hectares that looks like a deliberate “serve and avoid” to me…) and with the Radlett application process having predated the switching on of the 2008 Act.

The need case

The National Networks NPS sets out the need for SRFIs in paras 2.42 to 2.58:

“2.53 The Government’s vision for transport is for a low carbon sustainable transport system that is an engine for economic growth, but is also safer and improves the quality of life in our communities. The Government therefore believes it is important to facilitate the development of the intermodal rail freight industry. The transfer of freight from road to rail has an important part to play in a low carbon economy and in helping to address climate change.

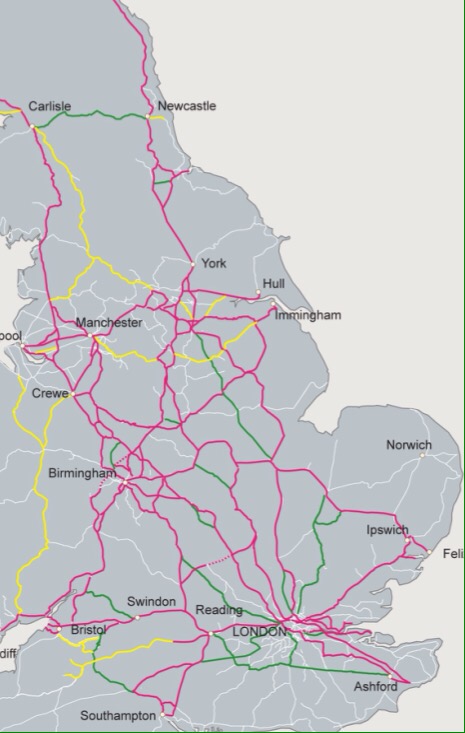

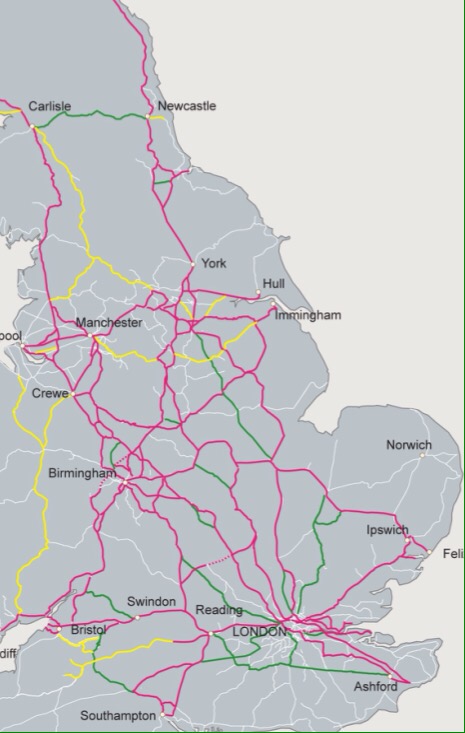

2.54 To facilitate this modal transfer, a network of SRFIs is needed across the regions, to serve regional, sub-regional and cross-regional markets. In all cases it is essential that these have good connectivity with both the road and rail networks, in particular the strategic rail freight network (see maps at Annex C). The enhanced connectivity provided by a network of SRFIs should, in turn, provide improved trading links with our European neighbours and improved international connectivity and enhanced port growth.

“2.56 The Government has concluded that there is a compelling need for an expanded network of SRFIs. It is important that SRFIs are located near the business markets they will serve – major urban centres, or groups of centres – and are linked to key supply chain routes. Given the locational requirements and the need for effective connections for both rail and road, the number of locations suitable for SRFIs will be limited, which will restrict the scope for developers to identify viable alternative sites.

2.57 Existing operational SRFIs and other intermodal RFIs are situated predominantly in the Midlands and the North. Conversely, in London and the South East, away from the deep-sea ports, most intermodal RFI and rail-connected warehousing is on a small scale and/or poorly located in relation to the main urban areas.

2.58 This means that SRFI capacity needs to be provided at a wide range of locations, to provide the flexibility needed to match the changing demands of the market, possibly with traffic moving from existing RFI to new larger facilities. There is a particular challenge in expanding rail freight interchanges serving London and the South East.”

Annex C strategic rail freight network map

These facilities are important for our economy, and for reducing vehicle emissions (not that there is any reference to this, or indeed any other supra-local planning interventions, in the Government’s draft air quality plan published on 5 May 2017). Unfortunately, the strategy in the NPS is very general. Whilst there are the references to London and the South East in the passages above, this is even less specific than the former Strategic Rail Authority’s Strategic Rail Freight Interchange policy March 2004, much argued over at inquiries, which asserted that “required capacity would be met by three or four new Strategic RFI” in London and the South East and that the “qualitative criteria to deliver the capacity mean that suitable sites are likely to be located where the key rail and road radials intersect with

the M25.”

Currently it is down to the private sector to identify sites which may meet the NPS criteria, with a wary eye on what other sites may be in the frame – a game not for the faint-hearted, meaning a very limited pool of potential promoters.

Since the NPS, we have had DfT’s Rail Freight Strategy 13 September 2016:

Para 53 “This Rail Freight Strategy will not set out proposals for new enhancements to the network nor specify in detail the freight paths that will be needed in future. These issues are being considered by DfT on a longer timescale as part of the long-term planning process for the rail network, which will consider priorities for the railway beyond the current control period (from 2019). To inform the industry’s advice to DfT as part of this process, Network Rail is currently consulting on a more detailed Freight Network Study. This considers the requirements of the rail network over the next 30 years and is intended to support the series of Route Studies that have been published or are under development by Network Rail.”

Will we see an amended National Networks NPS in the foreseeable future so as to give greater direction? I doubt it.

So now let’s look at the most likely candidates to serve London and the South East

Colnbrook

Those with long memories may recall Argent’s LIFE (London International Freight Exchange) scheme proposed on land to the north of the A4 at Colnbrook, near Slough. The then Secretary of State dismissed an appeal against refusal of planning permission on 20 August 2002, stating:

“The central issue remains […] where to strike the balance between Green Belt and sustainable transport interests. The proposal would be inappropriate development in the Green Belt and would harm the openness of the Green Belt, at the same time there are positive aspects including some sustainable transport benefits”.

“The Secretary of State continues to support the principle of encouraging more rail freight, but shares the Inspector’s judgement that the balance of benefits and disbenefits is against the LIFE scheme as currently proposed and that the general presumptions against inappropriate development in the Green Belt should apply”.

Goodman are now promoting a smaller SRFI on part of the site. Their scheme is now imaginatively called SIFE (Slough International Freight Exchange) and was the subject of a planning application in September 2010. It was refused by Slough Borough Council and an inquiry was due to take place into Goodman’s appeal in October 2012. However, the inquiry was then put in the sidings whilst the then Secretary of State decided whether to re-open an inquiry into the Radlett SRFI scheme, which he considered might have significant implications for SIFE. As it happened, due to delays in that inquiry process (of which more later), the SIFE inquiry was not rescheduled until The Radlett decision letter was issued in July 2014.

After a ten day inquiry in September 2015, the Secretary of State on 12 July 2016 dismissed Goodman’s appeal against refusal by Slough Borough Council of planning permission for SIFE. The Secretary of State addresses the extent to which there is a need for all three facilities (SIFE Colnbrook; Radlett, and Howbury Park):

“24. The Secretary of State has carefully considered the Inspector’s reasoning about need at IR12.88 – 12.103 and accepts the Inspector’s conclusion that the current policy need for a regional network has not been overcome by the SRFI at Radlett and SIFE is able to be regarded as a complementary facility as part of a wider network (IR12.104).

25. With regard to the Inspector’s analysis of other developments and sites at IR 12.105 – 12.106, the Secretary of State agrees that the NPS makes clear that perpetuating the status quo, which means relying on existing operational rail freight interchanges, is not a viable option.

26. The Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that there is a reasonable probability that Radlett will be operational in 2018 and there is the prospect of Howbury Park being progressed to implementation. In addition, rail connected warehousing is under development in Barking. On the downside, the geographical spread is uneven. There is a noticeable gap in provision on the west side of London, with Radlett being complementary to rather than an alternative to SIFE. SIFE would contribute to the development of a network of SRFI in London and the South East and a wider national network in accordance with the policy objective of the NPS (IR12.107).”

However he goes on to reach the following conclusions as to whether there are very special circumstances justifying inappropriate development in the green belt:

“13. The Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s comments at IR12.8, and like the Inspector, concludes that the appeal proposal would be inappropriate development in the Green Belt and that it is harmful as such. As the proposal amounts to inappropriate development he considers that, in the absence of very special circumstances, it would conflict with national policies and with the CS. Like the Inspector, the Secretary of State considers that the NPS does not change the policy test for SRFI applications in the Green Belt or the substantial weight to be attached to the harm to the Green Belt (IR12.8). For the reasons given by the Inspector at IR12.9 – 12.11, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s conclusion (IR12.12) that the proposed development would result in a severe loss of openness.

14. The Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector that the introduction of major development on the site, even if enclosed within well-defined boundaries, would not assist in checking sprawl and hence would conflict with a purpose of the Green Belt (IR12.13). For the reasons given by the Inspector at IR12.14, the Secretary of State agrees that the proposal would not be compatible with the purpose of preventing neighbouring towns merging into one another. The Secretary of State accepts the Inspector’s conclusion that the proposed development would encroach into the countryside. He agrees too that this conflict is not overcome by the proposed creation of new habitats and other aspects of mitigation in existing countryside areas (12.15). The Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s overall conclusion that these conflicts should be afforded substantial weight (IR12.18). The Inspector acknowledges that the proposed SRFI development’s location in the Green Belt may well be an optimum solution in relation to existing patterns of distribution activity, but like the Inspector, the Secretary of State concludes that this does not reduce the actual harm that would occur (IR12.19)”

His overall conclusions:

“40. The Secretary of State accepts that the most important benefit of the proposal is the potential contribution to building up a network of SRFIs in the London and South East region, reducing the unmet need and delivering national policy objectives. In addition, there is the prospect of SIFE being complementary to Radlett and other smaller SRFI developments and improving the geographical spread of these facilities round Greater London. In this context, the Secretary of State accepts that the contribution it would make to meeting unmet need is considerable.

41. He accepts too that SIFE would comply with the transport and location requirements for SRFIs to an overall very good standard. He acknowledges that sites suitable for SRFIs are scarce and the difficulty in finding sites in the London and South East region. On account of this factor, and the standard of compliance achieved, he affords meeting the site selection criteria significant weight. No less harmful alternative site has been identified in the West London market area, a factor which he affords considerable weight. Attracting less but nevertheless moderate weight are the economic benefits, the reduction in carbon emissions and improvements.

42. In common with the Inspector in her conclusion, the Secretary of State has been persuaded by the irreparable harm that would be caused to this very sensitive part of the Green Belt in the Colnbrook area, leading to the high level of weight he attaches to this consideration. Overall, the Secretary of State concludes that the benefits of the scheme do not clearly overcome the harm. Consequently very special circumstances do not exist to justify the development. Furthermore, he finds that planning conditions would not be able to overcome the fundamental harms caused to the Green Belt, Strategic Gap and Colne Valley Park and the open environment enjoyed by the local community. In addition, he has concluded that the proposal does not have the support of the NPS because very special circumstances have not been demonstrated.”

Goodman challenged the decision on the basis that it was wrong for the Secretary of State, in adjudicating the “very special circumstances” test, to give no weight to Goodman’s argument that it was inevitable that a Green Belt location is essential for meeting the need for an SRFI in this location. However the decision has been upheld: Goodman Logistics Developments (UK) Ltd v Secretary of State (Holgate J, 27 April 2017). Holgate J stated:

“It should be noted that Goodman did not advance the extreme argument that the need for another SRFI to serve London and the South East was such that it was inevitable that a a Green Belt site would have to be released for that purpose. There is no policy support for any such proposition. The NPS does not suggest that the need for a network of SFRIs, or for any particular SFRI, is a need to be met come what may, irrespective of the degree of harm which may be caused, or indeed the degree of need for an SRFI in a particular region. Instead, Goodman relied upon an “inevitability” which was qualified. The claimant argued that it is inevitable that another SRFI to serve the London and South East region will be located on a Green Belt site and harm to the Green Belt will occur, if the need for such a SRFI is to be met. The merits of the “inevitability” argument put forward by Goodman were therefore dependent upon the decision-maker’s assessment as to what importance or weight should be attributed to that need and whether that need should indeed be met after taking into account all the harm that would result.”

He goes on:

“The degree of harm that would result from the appeal proposal is only inevitable (in one sense) if the decision-maker concludes that the need for the SRFI and any other benefits flowing from the proposal are of such weight that the balance comes down in favour of granting planning permission. It is not in fact inevitable that the balance will be struck in that way

But if the “need” for SRFIs is not allowed to amount to “very special circumstances” for the purposes of green belt policy, and if there is room for a balancing of the seriousness of that need as against the degree of harm that would be caused, does this lead to unnecessary uncertainty right until the conclusion of the decision making process? Couldn’t the suitability in principle of development in the green belt have been resolved at an earlier stage, preferably via the national policy statement? Similarly, the uncertainties as to the inter-relationship between the three schemes. Why was a decision on Radlett (positive or negative) allowed to become a prerequisite to determining SIFE?

So what next for the site? As it happens, the proposed new runway at Heathrow Airport in combination with associated mitigation proposals and associated development would in fact take up most of the site in any event. Is this planning process now at least partly about establishing “no scheme world” value?

Radlett

Helioslough’s proposal for an SFRI on the former Radlett Aerodome site has a similarly lengthy – and even more convoluted – history. Two appeals had been dismissed for rail freight distribution proposals on the site, which again is in the green belt. The second appeal decision, dated 7 July 2010, turned on a conclusion by the Secretary of State that the Colnbrook site could be a less sensitive site than the Radlett site for an SRFI and that therefore “very special circumstances” for the development of the Radlett site had not been made out.

Helioslough successfully challenged that decision. On 1 July 2011 HH Judge Milwyn Jarman QC ordered that the Secretary of State‟s decision be quashed, holding that the Secretary of State had misconstrued the Strategic Gap policy in Slough’s. Core Strategy and consequently had failed to treat that as an additional policy restraint over and above the Green Belt designation. So the appeal fell to be redetermined by the Secretary of State.

Prior to redetermining it, the Secretary of State consulted with the parties as to whether to conjoin a re-opened inquiry with the inquiry that was to be held into the SIFE Colnbrook appeal. On 14 December 2012 he notified the parties that we was not going to re-open the inquiry but determine it on the basis of the evidence already before him. On 20 December 2012 he issued a letter indicating that he was minded to allow the appeal, subject to completion of a section 106 agreement.

St Albans City and District Council sought to challenge by way of judicial review the Secretary of State’s decision to not to re-open the inquiry. However that challenge was refused permission by Patterson J on 14 June 2013 (and a subsequent renewal application before Collins J failed).

As it happened, the “minded to grant subject to section 106 agreement” indication was unsatisfactory for the promoter too, which had problems completing a section 106 agreement due to land ownership difficulties (part of the site being owned by Hertfordshire County Council) which had led it to press for obligations to be secured by way of negative Grampian-style condition. Helioslough challenged the Secretary of State’s continued delay in issuing a final decision but permission to proceed with judicial review was rejected by John Howell QC sitting as a deputy judge on 1 July 2013.

A section 106 agreement was finally submitted and the Secretary of State granted planning permission in his decision letter dated 14 July 2014. His conclusions were as follows:

“In conclusion, the Secretary of State has found that the appeal proposal would be inappropriate development in the Green Belt and that, in addition, it would cause further harm through loss of openness and significant encroachment into the countryside. In addition the scheme would contribute to urban sprawl and it would cause some harm to the setting of St Albans. The Secretary of State has attributed substantial weight to the harm that would be caused to the Green Belt. In addition he has found that harms would also arise from the scheme’s adverse effects on landscape and on ecology and that the scheme conflicts with LP policies 104 and 106 in those respects.

53. The Secretary of State considers that the factors weighing in favour of the appeal include the need for SRFIs to serve London and the South East, to which he has attributed very considerable weight, and the lack of more appropriate alternative locations for an SRFI in the north west sector which would cause less harm to the Green Belt. He has also taken account of the local benefits of the proposals for a country park, improvements to footpaths and bridleways and the Park Street and Frogmore bypass. The Secretary of State considers that these considerations, taken together, clearly outweigh the harm to the Green Belt and the other harms he has identified including the harm in relation to landscape and ecology and amount to very special circumstances. Despite the Secretary of State’s conclusion that the scheme gives rise to conflict with LP policies 104 and 106, in the light of his finding that very special circumstances exist in this case he is satisfied that, overall the scheme is in overall accordance with the development plan”.

Inevitably, the council challenged the decision. They asserted that the Secretary of State had applied too strict a test in considering whether he could depart from conclusions he had reached in his initial decision and that the Secretary of State failed to take into account a recent decision that he had made on a nearby site. The challenge failed: St Albans City and District Council v Secretary of State (Holgate J, 13 March 2015).

So shouldn’t this be a scheme that is now proceeding, after all of that work? Reserved matters have been applied for, leading to local heat if a report of a recent planning committee is anything to go by. But the rub is that Hertfordshire County Council as land owner hasn’t made a decision as to whether to make its land available to enable the development to proceed.

Howbury Park

The third scheme is one in Crayford, again on green belt land, that was initially promoted by Prologis and secured planning permission on appeal in December 2007. However, due to the global financial crisis it did not proceed and the permission is now time expired.

Roxhill has now replaced Prologis as developer and has submitted fresh applications for planning permission to London Borough of Bexley and to Dartford Borough Council (the proposed access road is in Dartford’s administrative area).

Bexley members resolved to approve the scheme on 16 February 2017 but Dartford members resolved to reject it on 20 April 2017 following their officers’ recommendation. So presumably we may see yet another appeal.

The Bexley part of the scheme is of course within the remit of the Mayor of London, but not the Dartford part, so there is little that he can do by way of intervention. In any event, it will be seen from his 6 June 2016 Stage 1 report that he is not particularly providing a clear strategic lead on the issue:

“11. … The majority of the SRFI developments to date have been in the Midlands and the North, and the aspiration is to have a network of three SRFI around the M25, including this site at Howbury Park, South East London, Radlett, North London(approved by the Secretary of State) and Colnbrook, West London (decision awaited from the Secretary of State) to build a national network.”

“28 Although London Plan policy 6.15a Strategic Rail Freight Interchanges is supportive of the type of facility proposed due to identified strategic need, policy 6.15b caveats this support and sets out criteria which must be delivered within the facility.

A) The provision of strategic rail freight interchanges should be supported. Including enabling the potential of the Channel Tunnel Rail link to be exploited for freight serving London and the wider region.

B) The facilities must: (a) deliver model shift from road to rail; (b) minimise any adverse impact on the wider transport network; (c) be well related to rail and road corridors capable of accommodating the anticipated level of freight movements; and (d) be well related to the proposed market.

29 Supporting text paragraph 6.50 acknowledges that these types of large facilities can often only be located in the Green Belt. The Howbury Park site is referenced as a site potentially fulfilling these criteria, reflecting the previous planning permission. Paragraph 6.50 also states:

‘The Mayor will need to see robust evidence of savings and overall reduction in traffic movements are sufficient to justify Green Belt loss in accordance with policy 7.16, and localised increases in traffic movements.’ “

”38 The need for a SRFI is accepted, and is borne out through the NPS, the London Plan and the Inspector’s decision on the 2007 case. The applicant has made a compelling ‘very special circumstances’ case but GLA officers would advise further clarification should be sought on the biodiversity benefits of the proposal and the environmental benefits, notably whether the emission savings and overall reduction in traffic movements are sufficient to justify the loss of Green Belt in line with London Plan policy 6.15 and supporting paragraph 6.50. It should be noted that TfL has raised concerns in respect of the potential impact on the passenger rail network and has suggested conditions to limit the hours of operation of rail movements in and out of the SRFI. GLA Officers would want to know the full details of the potential impacts on the wider transport network (in line with London Plan policy 6.15B (b) and whether such conditions would hinder the operation and whether this would reduce the potential emission savings and traffic movements. GLA officers would also seek details of the proposed biodiversity management plan and compensatory measures. GLA officers would also expect a similar obligations package as that previously agreed to encourage the take up of rail use.

39 For the above reasons, at this stage, it is considered premature for GLA officers to make a concrete judgement as to whether the applicant’s very special circumstances case outweighs the identified harm to the Green Belt, and any other harm.”

Concluding thoughts

Even if your work never brings you into contact with the rail or logistic sectors, these convoluted stories must surely give rise to serious concerns. Successive governments have said that these types of facilities are needed in the public interest, for the sake of our national economy and to reduce polluting road freight miles. And yet they wash their hands of any responsibility for lack of delivery.

The consequences of not providing clear strategic guidance is that years are spent on expensive, contentious planning processes. Often by the time that a process has concluded the world has moved on and the process has to start all over again.

These are massively expensive schemes to promote. What can we do to make that investment worthwhile? If a site is unacceptable, can’t we indicate that at the outset and not many years later?

To what extent should land ownership issues be resolved at the outset of a major project?

Should the NSIP threshold be reduced? These schemes end up being determined at a national level anyway. Why not funnel them through a process that is more fit for purpose?

Why don’t we bite the bullet and arrive at more spatially specific policies in the National Networks NPS rather than leave it for promoters to read between the lines as to what the Government’s approach may end up being to particular proposals – particularly given the inevitably sensitive locations involved, often in the green belt? (Or is that taboo issue the answer to my question?).

Simon Ricketts 6.5.17

Personal views, et cetera