Even when it’s your day job in our planning world of imprecisely worded policies and the uncertainties of local and national politics, it can be hard enough to answer the question as to whether a proposed development project has a reasonable prospect of planning permission. But what if you are a county court judge? And when the law throws in some hypothetical assumptions?

One of the grounds under section 30(1) of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 which a landlord can rely on in opposing the grant to of a new tenancy to an existing business tenant is on the ground that “on the termination of the current tenancy the landlord intends to demolish or reconstruct the premises comprised in the holding or a substantial part of those premises or to carry out substantial work of construction on the holding or part thereof and that he could not reasonably do so without obtaining possession of the holding.”

The courts have held that the landlord must show that (1) it has the intention to demolish or reconstruct at least a substantial part of the premises and (2) there is a reasonable prospect of being able to bring about that intention.

That “reasonable prospect” second limb of the test was the subject of Warwickshire Aviation Limited and others v Littler Investments Limited (Birss J, 25 March 2019) and I will deal with that in a moment.

However, first to note that the Supreme Court late last year caused a minor earthquake in terms of how the first limb is to be interpreted, namely whether the landlord has a sufficient “intention“.

For a long time now it has been the practice of some landlords to come up with demolition or redevelopment schemes just to satisfy the test, schemes which they are prepared to undertake to the court that they will carry out (an undertaking which they will not need to give if, as has been usual, in the face of an evidenced intention the tenant resigns itself to defeat and cuts a deal – in which case the scheme can be abandoned).

As a result of S Franses Limited v The Cavendish Hotel (London) Limited (Supreme Court, 5 December 2018), that practice has been rendered much more difficult.

The case concerned a textiles dealership and consultancy in Jermyn Street, Mayfair, comprising the ground floor and basement of what is otherwise the Cavendish Hotel. It was refused a new tenancy on the basis that its landlord “intended” to carry out an absurd set of works, arrived at because of the difficulties in obtaining planning permission for earlier proposals to create new retail units. The landlord ended up proposing a set of works that did not require planning permission. First, the proposed “internal wall dividing the two proposed retail units stopped two metres short of the shopfront at ground floor level; and there was no external door to one of the units, so that it could be accessed only through the other. Secondly, the new scheme added more extensive internal works, many of which were objectively useless. They included the artificial lowering of part of the basement floor slab, in a way which would achieve nothing other than the creation of an impractical stepped floor in one of the units; the repositioning of smoke vents for no reason; and the demolition of an internal wall at ground floor level followed by its immediate replacement with a similar wall in the same place. The cost of the scheme was estimated by the landlord at £776,707 excluding VAT, in addition to statutory compensation of £324,000 payable to the tenant.

It is common ground that the proposed works had no practical utility. This was because, although the works themselves required no planning permission, it would be impossible to make any use of them at all without planning permission for change of use, which the landlord did not intend to seek. Planning permission would have been required because the scheme involved combining premises permitted for hotel use with premises permitted for sui generis use. In addition, one of the retail units was unusable without an entrance from the street. In accordance with a common practice in this field, the landlord supported its evidence of intention with a written undertaking to the court to carry out the works if a new tenancy was refused. The sole purpose of the works was to obtain vacant possession. The landlord’s evidence was that it was prepared to run the risk that the premises occupied by the tenant would be rendered unusable “in order to secure its objective of undertaking [the third scheme] and thereby remove the claimant from the premises.” The landlord submitted that “the works are thoroughly intended because they are a way of obtaining possession. That is all there is to it.” As the landlord’s principal witness put it, the third scheme was “designed purely for the purpose of satisfying ground (f).”

The landlord argued that its motives were irrelevant – all that mattered was its intention to carry out the works. However, the Supreme Court disagreed.

Lord Sumption: “the landlord’s intention to demolish or reconstruct the premises must exist independently of the tenant’s statutory claim to a new tenancy, so that the tenant’s right of occupation under a new lease would serve to obstruct it. The landlord’s intention to carry out the works cannot therefore be conditional on whether the tenant chooses to assert his claim to a new tenancy and to persist in that claim. The acid test is whether the landlord would intend to do the same works if the tenant left voluntarily.”

In consequence in future cases there will surely be a greater need for expert evidence in county court proceedings as to why a particular scheme of works has some commercial utility to the landlord other than just as a basis for a ground (f) opposition to a new tenancy.

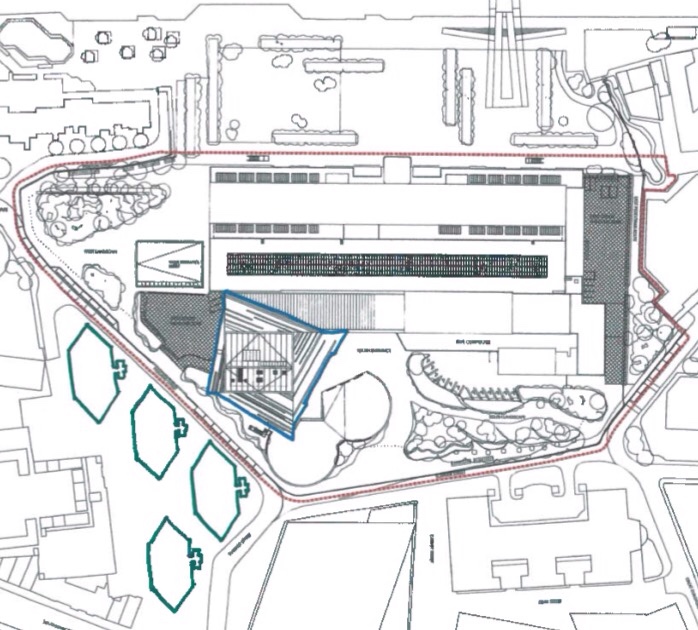

Back to the second limb and the Warwickshire Aviation case. The case had started in the county court, with seven separate aviation-related tenants of premises at Wellesbourne Mountford Airfield all faced with ground (f) opposition by their landlord to the grant of new tenancies on the basis that it intended to demolish their premises. There was a trial of the preliminary issue as to whether ground (f) had been made out. Planning permission for demolition would be required because permitted development rights had been taken away by way of an Article 4 direction. The landlord wished to bring to an end any aviation use on the airfield and instead to promote the site for residential development. The central issue at the four day trial was whether, against the planning policy background, there was a reasonable prospect that the local planning authority would grant planning permission for demolition, in the face of policies which included support for “enhancement of the established flying functions and aviation related facilities” at the airfield. Planning consultants gave expert evidence for the two sides, with very different conclusions.

One complication was the necessary hypothetical assumption that at the time of the notional planning application for demolition the tenants would have vacated and the current aviation related uses would have ceased. Given the landlord’s objectives, the county court judge found “there appears on legitimate and substantial economic/commercial grounds to be no realistic prospect, if consent for demolition was refused, of the Defendant re-instating aviation related use of the buildings. That would be a material consideration for the decision maker to have regard to” in the light of the relevant policies and therefore he concluded that there was a reasonable prospect that planning permission would be granted.

On appeal from the Birmingham County Court to the High Court, the tenants argued that “in planning terms the landlord’s future intentions are irrelevant and do not amount to a “material consideration” within s70(2) of the TCPA and s38(2) of the PACP. They argue while the land owner may well have sound commercial reasons for wanting to increase the profitability of its landholding and prevent further aviation use, those are quintessentially private rather than public interests.”

The judge on appeal rejected the argument. The relevant policy “rather than requiring developers to retain and support existing aviation related facilities at the airfield regardless of the circumstances, only states that developers are expected to contribute to the achievement of that objective “where it is appropriate and reasonable for them to do so”. As Littler submits, those words are wide enough to allow a developer to tell the decision maker that it does not intend to return the buildings to their previous aviation related uses for commercial reasons. The decision maker will assess if that stance is appropriate and reasonable in the circumstances. If the reasons are found to be genuine (as here), in that case it would be open to the decision maker to accept the stance of the developer. The result could well be that it would not be appropriate and reasonable to expect the developer to contribute to the achievement of the objective of retaining aviation related uses at Wellesbourne in that instance. Therefore the judge was entitled to approach the matter in the way he did.

Contrary to the […] appellants’ submission, this does not mean that the entire planning system can be subverted or frustrated because a landowner would always be able to succeed in obtaining planning permission for demolition or change of use simply by asserting an intention not to continue its existing use. That submission ignores the discretion in the relevant planning policy, ignores the fact that there were a range of other uses available not requiring planning permission (this is addressed in Ground C below) and ignores the fact that the judge specifically considered whether the reasons given by Littler were substantial and genuine.”

The appeal judge agreed with the county court judge that policies in a recently adopted neighbourhood plan did not make a significant difference to the issues.

Finally the appeal judge rejected the submission that the judge at first instance had applied too stringent a test in assessing the likelihood of aviation related uses resuming if permission for demolition were to be refused.

Regardless of what the correct answer actually was on the evidence, one can see the difficulties inherent in determining the hypothetical question on which the case turned. I’m no landlord and tenant lawyer but isn’t “reasonable prospect” just setting the bar too low? Of course the landlord is going to be dead-set against a continuation of the relevant use – that’s why it has gone to the expense of opposing a new tenancy. If that is relevant, doesn’t that leave the landlord holding all the cards? Or is the reality that business tenants have to accept that their right to a new tenancy will always be precarious? Another issue for the Supreme Court one day perhaps?

Landlord and tenant lawyers, you are welcome to set me straight on any of this.

Simon Ricketts, 20 April 2019

Personal views, et cetera