Relax – this blog post is about on shore wind turbines rather than nuclear fallout.

But there is somewhat of a “dig for victory” feel to our current conversations about energy. If we all just turn down our thermostats by one degree and so on.

Against the urgent need for greater energy security, against the escalating costs of energy and fuel (which make “levelling up” a side show) and of course against the largest and most relentless horseman of the apocalypse, climate change – there is one central question: How can we reduce our energy requirements and maximise the potential of our “home grown” sources of energy?

Following this 8 March Government press statement UK to phase out Russian oil imports (phasing out to be by the end of this year), we await a statement from the prime minister next week on the future of UK energy supply. He was quoted last week as follows:

“We need to intensify our self reliance as a transition with more hydrocarbons, but what we also need to do is go for more nuclear and much more use of renewable energy,” he said. “I’m going to be setting out an energy strategy and energy supply strategy for the country in the days ahead.”

This is not going to be uncontroversial, both by reference to “more hydrocarbons” (see eg Johnson hints UK oil and gas output must rise to cut dependence on Russia (The Guardian, 7 March 2022)) but also unfortunately in relation to renewables, the further encouragement of which should surely be a no-brainer.

We had a wide-ranging clubhouse discussion back on 8 February 2022, Renewable energy and using less energy: are you plugged in? which is worth listening back to (it includes discussion of energy reduction and of what is happening in relation to off shore wind energy which this blog post will not), and there is also my 23 October 2021 blog post Net Zero Strategy: We Can Have Cake & Eat It, but all that seems a long time ago set against recent events.

Warning: this blog post only considers England’s, particularly troubled, policy position, rather than the rest of the United Kingdom.

The July 2021 update to the NPPF did not contain any specific changes in relation to planning for climate change. Paragraph 152 (previously paragraph 148) still reads:

“The planning system should support the transition to a low carbon future in a changing climate, taking full account of flood risk and coastal change. It should help to: shape places in ways that contribute to radical reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, minimise vulnerability and improve resilience; encourage the reuse of existing resources, including the conversion of existing buildings; and support renewable and low carbon energy and associated infrastructure.”

When the update was published the Government’s response to consultation stated that 20% of respondents to that draft section of the framework “recognised the importance of climate change and indicated a need for stronger terminology to reflect this, such as specific references to the net zero target and emphasis on renewable energy” and stated that the Government is “committed to meeting its climate change objectives and recognises the concerns expressed across groups that this chapter should explicitly reference the Net Zero emissions target. It is our intention to do a fuller review of the Framework to ensure it contributes to climate change mitigation/adaptation as fully as possible, as set out in the [planning white paper].”

So we expect changes to the NPPF to strengthen planning policies on climate change. Can we expect any change of policy in relation to on-shore wind in particular?

If you recall, following its 2015 election manifesto pledge, the Government significantly toughened its stance in relation to on shore wind. Greg Clark issued this written ministerial statement on 18 June 2015:

“I am today setting out new considerations to be applied to proposed wind energy development so that local people have the final say on wind farm applications, fulfilling the commitment made in the Conservative election manifesto.

Subject to the transitional provision set out below, these considerations will take effect from 18 June and should be taken into account in planning decisions. I am also making a limited number of consequential changes to planning guidance.

When determining planning applications for wind energy development involving one or more wind turbines, local planning authorities should only grant planning permission if:

· the development site is in an area identified as suitable for wind energy development in a Local or Neighbourhood Plan; and

· following consultation, it can be demonstrated that the planning impacts identified by affected local communities have been fully addressed and therefore the proposal has their backing.

In applying these new considerations, suitable areas for wind energy development will need to have been allocated clearly in a Local or Neighbourhood Plan. Maps showing the wind resource as favourable to wind turbines, or similar, will not be sufficient. Whether a proposal has the backing of the affected local community is a planning judgement for the local planning authority.”

New subsidies for on shore wind were also ended.

The stance flowed through to the NPPF and the relevant paragraph remains – supportive of renewable energy in principle but with a killer footnote in relation to on shore wind:

“158. When determining planning applications for renewable and low carbon development, local planning authorities should:

(a) not require applicants to demonstrate the overall need for renewable or low carbon energy, and recognise that even small-scale projects provide a valuable contribution to cutting greenhouse gas emissions; and

(b) approve the application if its impacts are (or can be made) acceptable 54 . Once suitable areas for renewable and low carbon energy have been identified in plans, local planning authorities should expect subsequent applications for commercial scale projects outside these areas to demonstrate that the proposed location meets the criteria used in identifying suitable areas.”

Footnote 54:

“(54) Except for applications for the repowering of existing wind turbines, a proposed wind energy development involving one or more turbines should not be considered acceptable unless it is in an area identified as suitable for wind energy development in the development plan; and, following consultation, it can be demonstrated that the planning impacts identified by the affected local community have been fully addressed and the proposal has their backing.”

BEIS’s December 2021 document Community Engagement and Benefits from Onshore Wind Developments – Good Practice Guidance for England is, I suspect, largely wishful thinking without a remotely encouraging policy position. Is anyone aware of many (any?) local or neighbourhood plans which actually do identify suitable areas for wind energy development?

It seems that the wind could soon be changing if these media pieces are to be believed:

Relaxing rules on wind farms could ease gas crisis (The Times, 9 March 2022)

BEIS to tackle onshore wind planning restrictions in England (renews.biz, 10 March 2022)

The Government has of course been consulting on its suite of energy national policy statements, which set the policy basis for the determination of development consent order applications for nationally significant infrastructure projects. The draft national policy statement for Renewable Energy Infrastructure (EN‐3) (September 2021) is not currently relevant to on shore wind, as on shore wind projects were entirely removed from the NSIP system. However, could we see a volte face on that restriction too?

It was interesting last week to read the detailed 9 March 2022 House of Commons briefing paper research paper on large solar farms and the Hansard transcript of the Westminster Hall debate on the subject. As with on shore wind, there are of course conflicting priorities to be weighed up – with on shore wind it is most often issues as to effect on protected landscapes and heritage assets and with solar farms most often the use of productive farm land (after all, food security is possibly as important as energy security). I wonder whether the position in relation to solar farms would be clearer if the NPPF reflected the language of the draft renewable energy infrastructure NPS (which of course only applies to solar farms of 50 MW capacity or above):

“Whilst the development of ground mounted solar arrays is not prohibited on sites of agricultural land classified 1, 2 and 3a, or designated for their natural beauty, or recognised for ecological or archaeological importance, the impacts of such are expected to be considered […]. It is recognised that at this scale, it is likely that applicants’ developments may use some agricultural land, however applicants should explain their choice of site, noting the preference for development to be on brownfield and non-agricultural land.”

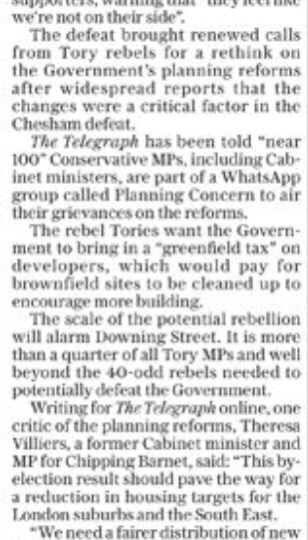

But back to the big picture – what direction are the prime minister’s announcements likely to take? This is such a precarious moment for the country’s approach to the climate crisis, with siren calls from the likes of Farage for a “net-zero referendum” and from some, equally opportunistically, even for a reversal of the Government’s ban on fracking.

Dangerous times.

Simon Ricketts, 12 March 2022

Personal views, et cetera

PS no Clubhouse this week, due to MIPIM for some. We return on the 22 March – subject yet to be announced!