I’ve mainly called this blog post “small changes” because that is the name of a beautiful, calming and rather lush album by Michael Kiwanuka released last year. Perhaps your social media timeline needs that sort of cleanse? Mine does regularly.

But I was also thinking of that old David Brailsford British Cycling philosophy about marginal gains (“The whole principle came from the idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike, and then improved it by 1%, you will get a significant increase when you put them all together”) and of the successive incremental changes that the government has been making to the planning system, most recently those measures flagged in the 28 May 2025 MHCLG press release as Government backs SME builders to get Britain building, measures which were the subject of three consultation documents published that day:

- Reforming Site Thresholds (consultation closes on 9 July 2025)

- Reform of Planning Committees (consultation closes on 23 July 2025)

- (from DEFRA) Improving the implementation of biodiversity net gain for minor, medium and brownfield development (consultation closes on 24 July 2025) (and for completeness there is also a further consultation paper Biodiversity net gain for nationally significant infrastructure projects – also with consultation closing on 24 July 2025).

All of this follows last Sunday’s Speeding Up Build Out consultation (consultation closing 7 July 2025), which I summarised that day in my blog post Now Build.

It is an interesting, maybe theoretical, question as to whether system changes are better announced and delivered in one go (soaking up all the political heat at once) or in the current lapping waves. It is also interesting to see the political heat rising from different quarters in relation to different elements.

Concern has been expressed from environmental interest groups and a number of firms providing ecological services, as to Part 3 of the Planning and Infrastructure Bill (nature recovery – see my 11 May 2025 blog post Nature Recovery Position where I tentatively suggest a middle ground).

The Speeding Up Build Out announcement then led to an outcry from many in the development world – how dare the government threaten developers with being blacklisted, fined or having land compulsorily acquired if they delayed unreasonably in building out planning permissions etc etc? I explain in my 25 May 2025 Now Build piece why I don’t think that should be a real concern and why, if only for pragmatic political reasons, the government has to have basic protections along these lines in place. But that was based on me focusing on the working paper and consultation document, not on the government’s PR spin, which I think was unnecessarily overblown, particularly:

- That tweet from the prime minister (NB what is the government doing still being on X in any event? Full marks to Matthew Pennycook and others for using Bluesky).

- That MHCL press release which took a tone which was inconsistent with the documents: ‘Get on and Build’ Deputy Prime Minister urges housebuilders .

All that developer-demonisation (“Developers who repeatedly fail to build out or use planning permissions to trade land speculatively could face new ‘Delayed Homes Penalty’ or be locked out of future permissions by councils”), whereas I’m not sure anyone would disagree with what is actually said in the working paper itself:

“The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and others have concluded that most homes in England are not built as fast as they can be constructed, once permission is granted, but only as fast as the developer expects to sell them at local second-hand market prices. This leads to a build out rate for large sites which can take decades to complete. While it is commercially rational for developers to operate in this way, the systemic impact is a lower level of housebuilding than we need. The government is therefore committed to taking firm action to ensure housebuilding rates increase to a level that makes housing more affordable for working people.

In the public debate on housebuilding rates, 3 related concepts are often confused.

a. Land banks are, for the most part, a normal part of the development system. Developers hold a pipeline of sites at all stages of the planning process, to avoid stop/starts between schemes. In its 2024 study, the CMA found no evidence of current land banks systemically distorting competition between housebuilders. We do, however, have concerns that certain types of contracts over land prior to its entry into the planning system (which can be part of ‘strategic’ land banks) can be a barrier to entry for SME developers. We are therefore legislating to make Contractual Control Agreements (‘option agreements’) more transparent, to help diversify the industry and reduce barriers to entry for SME builders.

b. Delayed or stuck sites are those at all stages of the planning and building process (including with full planning permission) that are delayed, not building out, or only building out very slowly due to a problem that the developer or landowner is struggling to resolve themselves. Often this is due to the discharge of a planning condition, an issue raised by a statutory consultee, a newly discovered site issue, or the developer running into financial difficulties. We have created the New Homes Accelerator to tackle this sort of blockage … and get stuck sites moving. In wider cases, sites may be stuck in negotiations over suitable S106 contributions, sometimes because the promoter has overpaid for the land not fully factoring in the policy requirements set out in planning policy. In this paper we consider further reforms to the Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) process, relevant to stalled sites.

c. Slow build out is where sites have full planning permission, are being built, but the pace of building is slower than it could be under different development models and incentives. Multiple market studies have found that most large housing sites are built at the pace the homes can be sold at current second-hand market prices, rather than the pace at which they could be constructed if pre-sold (i.e. to an institutional landlord). The rate of building consistent with selling at local second-hand market prices is known within the industry as the ‘absorption rate’. The Letwin Review concluded that local absorption rates were a “binding constraint” on build out rates. The CMA observed, that “the private market will not, on its own initiative, produce sufficient housing to meet overall housing need, even if it is highly competitive”.

So that was the furore earlier this week. And then when Wednesday’s announcements were made, environmentalists focused on the potential rolling back of the statutory BNG regime from smaller projects and opposition politicians turned on the (not new, but in my view improved) proposals to ensure that more applications are determined through use of planning officers’ delegated powers rather than Planning Committee.

You can’t please all the people all the time…

What is the thrust of the latest changes?

The starting point is to change the current categorisation of planning applications for residential development from those for “minor” development” and those for “major” development, so as to introduce a “medium” development category.

The categories would be:

- Minor Residential Development – fewer than 10 homes /up to 0.5 ha (and within that a sub-category of 1b. Very small sites – under 0.1ha)

- Medium Residential Development – between 10-49 homes/up to 1.0 ha

- Major Residential Development – 50+ homes / 1+ hectare

In due course, consideration would be given to appropriate categories for non-residential development.

The following would apply to each category:

Minor

- streamlining requirements on Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) including the option of a full exemption

- retaining the position that affordable housing contributions are not required on minor development

- retaining the position that sites of fewer than 10 units are exempt from paying the proposed Building Safety Levy (BSL)

- retaining the shorter statutory timeframe for determining minor development at 8 weeks “however we will take steps to improve and monitor performance so SMEs can expect a better service”

- reducing validation requirements “through setting clearer expectations in national policy on what is reasonable, which could form part of the forthcoming consultation on national policies for development management”

- requiring that all schemes of this size are delegated to officers and not put to planning committees as part of the National Scheme of Delegation.

- reviewing requirements for schemes of this size for consultation with statutory consultees “instead making use of proportionate guidance on relevant areas. This forms part of our review of statutory consultees”

On the “very small sites” sub-category:

“The government will consult on a new rules-based approach to planning policy later this year through a set of national policies for development management. This will include setting out how the government intends to take forward relevant aspects of the proposals contained in the previous ‘Brownfield Passport’ working paper.”

“The government is therefore proposing to further support the delivery of very small sites through:

- providing template design codes that can be used locally for different site size threshold and typologies – which will take a rules-based approach to design to help identify opportunities and enable faster application processes

- using digital tools to support site finding and checking compliance of design requirements on specific sites.”

Medium

- simplifying BNG requirements “reducing administrative and financial burdens for SME developers and making it easier for them to deliver BNG to help restore nature on medium sites by consulting on applying a revised simplified metric for medium sites. Further details are set out Defra’s consultation on potential BNG changes offering stakeholders the opportunity to give their views on this issue.”

- exploring exempting these sites from the proposed Building Safety Levy “we intend to lay regulations for the Building Safety Levy in Parliament this year (as set out in our response to our technical consultation) and the Levy will come into effect in Autumn 2026. As part of this working paper, we are keen to explore whether, if introduced, medium sites should also be exempt from paying the Levy”

- exempting from build out transparency proposals

- maintaining a 13-week statutory time period for determination “in line with major development – but specifically tracking performance of these types of developments directly so SMEs can expect a better service”

- including the delegation of some of these developments to officers as part of the National Scheme of Delegation

- ensuring referrals to statutory consultees are proportionate “and rely on general guidance which is readily available on-line wherever possible. This forms part of our review of statutory consultees”.

- uplifting the Permission in Principle threshold “allowing a landowner or developer to test for the principle of development for medium residential development on a particular site without the burden of preparing an application for planning permission. We recognise take up of Permission in Principle by application for minor residential development has been relatively limited since its introduction in 2017, and we would therefore like to gauge the appetite for this reform before exploring further”

- minimising validation and statutory information requirements “through setting clearer expectations in national policy which could form part of the forthcoming consultation on national policies for development management”

There is also an important reference to streamlining section 106 agreement negotiations:

“We … welcome views and evidence on:

1. the specific barriers facing SMEs in agreeing s.106 obligations – including availability of willing and suitable Registered Providers

2. what role national government should play in improving the process – including the merits of a standardised s.106 template for medium sites

3. how the rules relating to suitable off-site provision and/or appropriate financial payment on sites below the medium site threshold might be reformed to more effectively support affordable housing delivery, where there is sufficient evidence that onsite delivery will not take place within a suitable timeframe and noting the government’s views that commuted sums should be a last resort given they push affordable housing delivery timescales into the future.”

(I will be doing a separate blog post on that one).

Major

“This working paper primarily considers targeted changes and easements to sites below 50 homes. Sites above 50 will benefit from overall government reforms to the planning system – including those set out in the revised National Planning Policy Framework published in December, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, and future reforms to statutory consultees and through emerging national policies for development management.

Nevertheless – the government is interested in views in response to this working paper on:

- applying a threshold for mixed tenure requirements on larger sites – as set out in the government’s working paper on speeding up build out, we are considering a range of options to set a threshold whereby mixed tenure development should apply – including at 500 units. We welcome further views on the right threshold – and on whether and how there should be some discretion for Local Planning Authorities – ahead of consulting on the policy as part of a consultation on national policies for development management and a revised National Planning Policy Framework later this year.”

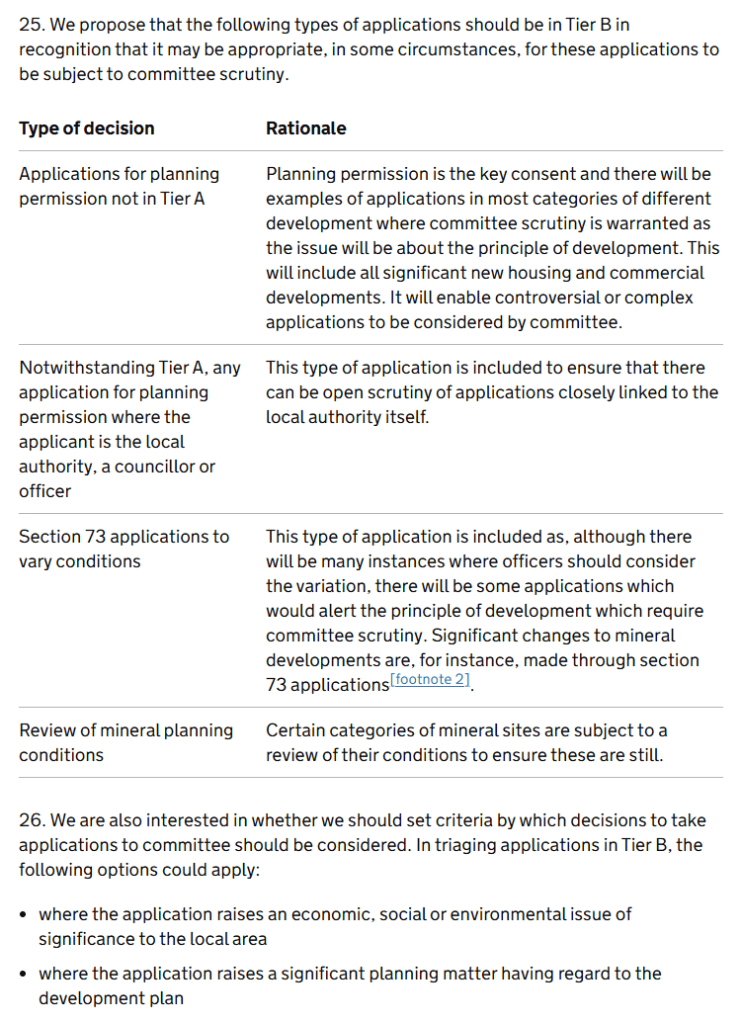

Turning to the paper on reforming planning committees, thankfully the thinking has moved away from taking into account whether or not a proposal is in compliance with the development plan (which would have led to endless arguments and disputes). Instead, the proposal is that a scheme of delegation would be introduced which would have two tiers:

“Tier A which would include types of applications which must be delegated to officers in all cases; and

Tier B which would include types of applications which must be delegated to officers unless the Chief Planner and Chair of Committee agree it should go to Committee based on a gateway test.”

“We propose the following types of applications would be in Tier A. This is in recognition that they are either about technical matters beyond the principle of the development or about minor developments which are best handled by professional planning officers:

- applications for planning permission for:

- Householder development

- Minor commercial development

- Minor residential development

- applications for reserved matter approvals

- applications for s96A non-material amendments to planning permissions

- applications for the approval of conditions

- applications for approval of the BNG Plan

- applications for approval of prior approval (for permitted development rights)

- applications for Lawful Development Certificates

- applications for a Certificate of Appropriate Alternative Development”

Note: “we are keen for views whether there are certain circumstances where medium residential developments could be included in Tier A. For instance, given the scale and nature of residential development in large conurbations such as London, we could specify medium residential development in these conurbations should be included in Tier A (as well as minor residential development), while in other areas, only minor residential development would fall within Tier A.”

Tier B:

There is also a proposal to limit the number of members of a planning committee to 11 and to introduce a national training certification scheme for planning committee members.

I will do a separate blog post on the BNG changes at some point but in the meantime Annex A to the DEFRA consultation paper is a good summary of the various proposals.

I think that’s enough for now…

Simon Ricketts, 31 May 2025

Personal views, et cetera

“Small changes

Solve the problems

We were revolving in your eyes

Wait for me

All this time, we

Knew there was something in the air“

(c) M Kiwanuka

Extract from album sleeve