If anyone doesn’t think that the Community Infrastructure Levy urgently needs reform, do read this 1 March 2017 VOA ruling on one of many thorny issues that arise constantly in practice: how to calculate indexation (as well as how to calculate chargeable floorspace) in relation to section 73 permissions that amend pre-CIL permissions. The copy of the ruling in the link to the gov.uk website is redacted but I can tell you that around £3m turned on the decision relating to a development of 527 dwellings. The authority in question (I will preserve anonymity) has been interpreting the Regulations in a way which it asserts to be literal and correct, but which leads to unfairly onerous liability arising (which for some people arises completely out of the blue by way of revised liability notices being served).

The VOA member considered that the authority’s approach “is wrong and undermines the purpose of regulation 128A” (the regulation that seeks to avoid double charging in the case of development pursuant to section 73 permissions). I understand that the issue may now reach the High Court by way of judicial review. As with any tax legislation, the dilemma is as to what room is there for a purposive interpretation, however unfair the consequences of a literal reading. After all, see R (Orbital Shopping Park Swindon) Limited v Swindon Borough Council (Patterson J, 3 March 2016):

“…not only would the defendant’s approach be contrary to the whole approach to the interpretation of planning permissions it would be contrary to constitutional principles. As was said in Vestey v Inland Revenue Commissioners [1980] AC 1148 by Lord Wilberforce:

”Taxes are imposed upon subjects by Parliament. A citizen cannot be taxed unless he is designated in clear terms by a taxing Act as a taxpayer and the amount of his liability is clearly defined.

A proposition that whether a subject is to be taxed or not, or, if he is, the amount of his liability, is to be decided (even though within a limit) by an administrative body represents a radical departure from constitutional principle. It may be that the revenue could persuade Parliament to enact such a proposition in such terms that the courts would have to give effect to it: but, unless it has done so, the courts, acting on constitutional principles not only should not, but cannot, validate it.”

In that case a literal interpretation was to the benefit of the payer rather than the authority. Patterson J underlined “the importance of a close and clear analysis of what the statute actually requires“.

The problem is that the 2010 Regulations are a hopeless mess; anything but clear to payer or authority alike – the antithesis of good tax legislation or indeed good planning legislation. The successive sets of amendments in 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 have resolved some problems, ignored others and created new ones. Due to ambiguities in the Regulations, CIL liability arising from a development is in many cases dependent on the approach being taken by individual collecting authorities, which is plainly contrary to the rule of law as well as wasteful of the time and money of all concerned. Planning consultants are having to act as tax accountants, with very large amounts of money at stake, dependent not just on an accurate reading of the legislation that accords with the collecting authority’s approach (unless there is to be an appeal to the VOA) but on service of the correct notices at the correct time – the process does not allow for any mercy on the part of the authority.

Of course the planning system has from its outset wrestled with two core unresolved issues:

– The extent to which the system should have any land value capture role

– Apportionment of responsibilities between the state and developers/land owners for infrastructure delivery/funding.

CIL is the latest attempt to square the circle but has proved hopelessly inefficient.

For an excellent, detailed, analysis of the underlying issues, still nothing beats Tom Dobson’s 2012 paper to the Oxford Joint Planning Law Conference.

Tom of course subsequently was one of the team, led by Liz Peace, appointed by the Government in November 2015 to:

“Assess the extent to which CIL does or can provide an effective mechanism for funding infrastructure, and to recommend changes that would improve its operation in support of the Government’s wider housing and growth objectives.”

Whilst the political reverberations of Brexit have been an unwarranted distraction from things that might actually help to improve lives and provide homes, it is so disappointing that the review team’s report was only published in February 2017, alongside the Housing White Paper. (Why was it held up till then? There is no read-across to the white paper proposals). The report is dated October 2016 but its contents were an open secret as long ago as June last year (see my CIL BILL? 3.6.16 blog post). Not only that but the Government has indicated that it will not be responding to the report’s recommendations until this Autumn’s budget. This presumably means no substantial changes until April or October 2018 at the earliest.

The review team considered four options:

– do nothing

– abolition

– minor reform

– more extensive reform

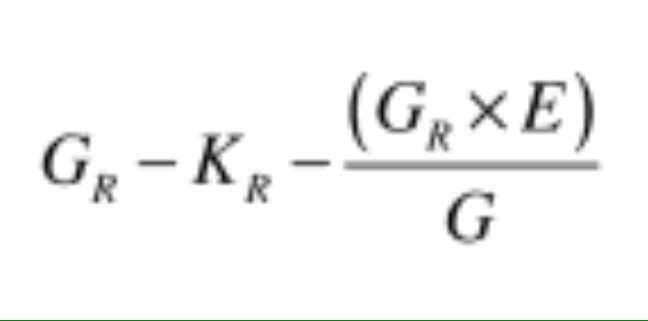

The report is a solid piece of work, well argued and rooted in experience. It identifies CIL’s failings (raising less money than anticipated, over-complicated, opaque) and firmly recommends extensive reform, particularly the replacement of the current system with a more standardised approach of Local Infrastructure Tariffs (LITs) and, in combined authority areas, Strategic Infrastructure Tariffs (SITs). LITs would supposedly be set at a low level calculated by reference to a proportion of the market value per square metre of an average three bedroom property in the local authority area, although the “example rates” in appendix 5 of the report are not particularly low given that there would be far fewer exemptions and reliefs and less opportunity to net off existing floorspace:

* £20 – £90 per m2 for Authorities in the North of England

* £30 – £90 per m2 for Authorities in the Midlands

* £30 – £220 per m2 for Authorities in the South and East of England

* £50 – £440 per m2 for London Boroughs

For developments of ten dwellings or more, there would be a return to the flexibility of section 106 for provision of site-specific infrastructure (netting off LIT liability) and of course abolition of the pooling restriction (come on government, if you do nothing else, remove the pooling restriction – even Donald Trump would be able to achieve that!).

There would be transitional arrangements, with the review team speculating that these could take us to the end of this Parliament in 2020. Alas, with subsequent slippages even that now looks optimistic.

What do we think the Government will do with the report? It is worrying that Gavin Barwell was talking at MIPIM of somehow including affordable housing in any revised system (see for instance Inside Housing’s article 24 March 2017). Keep it simple!

My personal guess is that significant change may well be too much for this government at this time. If so, ministers need to face that reality and it really is urgent that we at least push for Plan B: a further set of amending Regulations (preferably in the form of a consolidated version of the 2010 Regulations), putting right what we can, including abolition of the pooling restriction, alongside a clearer approach to indexation, to section 73 permissions and to payments in kind. The report called for interim measures but without setting them out in detail.

Many of you remain in the “kill CIL” camp. I recognise that the CIL review team’s recommendations are radical but to go one step further and lose any levy or tariff mechanism would in my view be impractical. For bigger schemes, section 106 agreements definitely have advantages (as long as the negotiation process can be as streamlined as possible and the authority’s requirements signposted in policies) but for smaller projects a standardised approach should in theory leave everyone knowing where they stand – and another major lurch to a new system would inevitably have unanticipated outcomes.

That June 2016 blog post was my first. And this is my 50th, with no real progress on CIL in the meantime. Gavin Barwell has rightly won many plaudits as planning minister but for many of us his real test will be to clear up quickly this CIL mess created by his predecessors (the coalition government in 2010 should have ditched it in the way that the Conservatives’ Open Source Planning manifesto document had suggested). As politicians love to say about most things, but true in the case of CIL, it’s broken.

Simon Ricketts 25.3.17

Personal views, et cetera