This weekend you will be worried that someone in the pub is going to say “hey, you’re a planner! … what’s the difference between a mayoral strategic authority, non-mayoral foundation strategic authority and single local authority foundation strategic authority; and between a CCA and a CA; and between the community right to bid and the community right to buy?”

You definitely need to be prepared and, rather than staying at home instead, there are probably three main options:

- You could read the 338 page Bill that was introduced into the House of Commons on 10 July 2025, perhaps alongside the 156 pages of explanatory notes and 237 pages of impact assessment.

- You could channel your inner Angela Rayner, by way of MHCLG’s 10 July 2025 press release or, for a deeper dive, a guidance document published by MHCLG, which serves to put the proposals within the Bill within a wider reform context.

- You could (and have indeed already started to) read this bluffer’s guide (this bluffer being me).

Confession: I have only scrolled through the material once so far just identifying what seemed to be most immediately relevant. There will be much that I have missed.

Much of the Bill serves to give effect to proposals within the English Devolution White Paper (16 December 2024) which I commented on from a planning perspective in my 18 January 2025 blog post Viva La Devolution although there is much more besides.

Anyway, here is some stuff that may be useful:

The Bill is really about four main things (quoting from MHCLG’s guidance document):

- “Devolution: describing devolution structures, outlining and expanding powers for Mayors and authorities through the new Devolution Framework and explaining routes to devolution for places that don’t have it.”

- Local government: ensuring the process for local government reorganisation supports the ambition in the White Paper, outlining changes to local authority governance, reforming accountability and introducing effective neighbourhood governance structures to amplify local voices.

- Communities: giving more power to local communities to purchase assets of community value and …”

- (the guidance document includes this under the “communities” heading but it is of wider relevance than that) abolishing upwards only rent review provisions in commercial leases.

Devolution

Devolution deals have to date been arrived at in ad hoc fashion. The Bill allows the government to roll out a standardised devolution framework. I summarised the different types of strategic authority in my January 2025 blog post, but MHCLH have now published this series of five “Devolution Framework Explainers” , on:

- Established mayoral strategic authorities

- Mayoral strategic authorities

- Non-mayoral foundation strategic authorities

- Single local authority foundation strategic authorities

In relation to roads, strategic authorities will be required to set up and coordinate a “key route network”, comprising the most important roads in their area, in respect of which they will have various powers of direction and the power to set traffic reduction targets – and will have the role of licensing bike and e-bike hire schemes.

In relation to planning, they will have equivalent powers to those of the London Mayor; in addition to SAs’ duty to prepare a spatial development strategy, the mayors of combined authorities and combined county authorities will have the power to direct refusal of planning applications of potential strategic importance (Regulations will need to set out what the thresholds will be) or to call them in for their own determination. They will be able to prepare mayoral development orders, establish mayoral development corporations and, if there is an adopted SDS, levy Mayoral CIL. Mayoral SAs will also need to prepare a local growth plan.

Mayors will be able to appoint and renumerate “Commissioners” to lead on particular statutory “areas of competence”.

Mayors will be elected via the supplementary vote system, rather than “first past the post” (as was the system prior to May 2024). They will be able to be the police and crime commissioner for their SA area. They will not be able to moonlight as a member of Parliament.

What is all this likely to mean for particular areas? I’m glad you asked me that! MHCLG has also now published a series of 16 “Area Factsheets”, providing “information on areas benefitting from English devolution, including electoral terms, route to established status, police and fire functions, distinctive governance arrangements and local government reorganisation”, for:

- Cambridgeshire and Peterborough

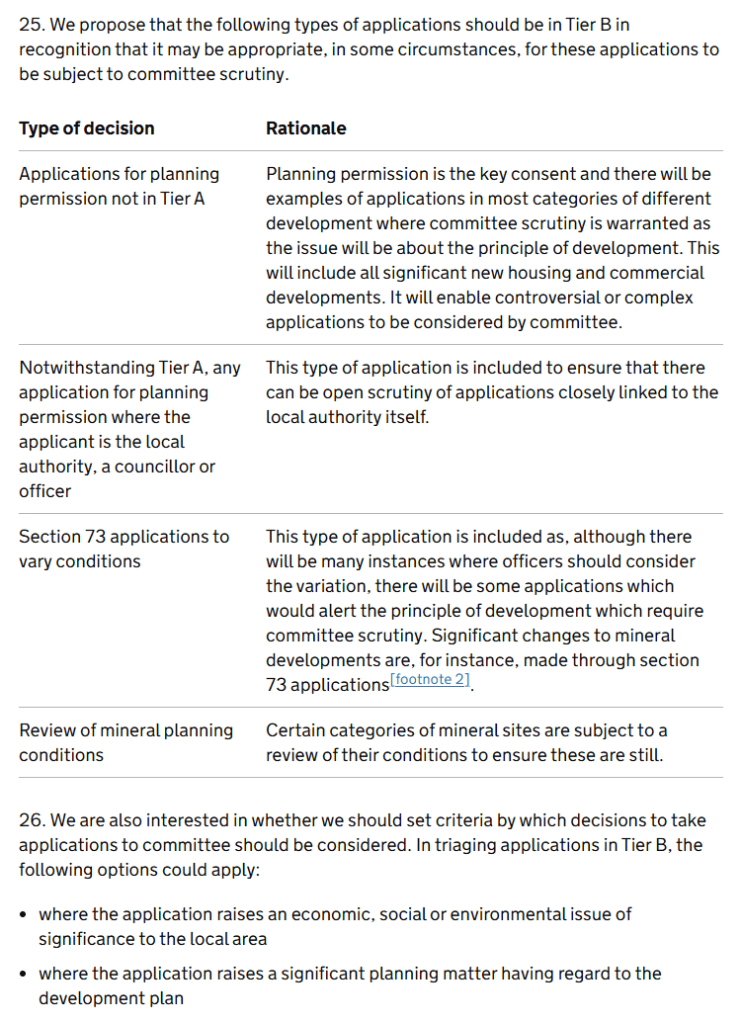

- Devon and Torbay

- East Midlands

- Greater Lincolnshire

- Greater London Authority

- Greater Manchester

- Hull and East Yorkshire

- Lancashire

- Liverpool City Region

- North East

- South Yorkshire

- Tees Valley

- West Midlands

- West of England

- West Yorkshire

- York and North Yorkshire

Local government

This includes the power for the Secretary of State to direct two-tier councils to submit proposals as to how to become a single unitary tier and in some cases to direct particular unitaries to submit a proposal to merge with each other. The cabinet system will be compulsory for local authorities and there will be no new local authority mayors.

“The Bill will empower communities to have a voice in local decision by introducing a requirement on all local authorities in England to establish effective neighbourhood governance. The requirement for local authorities to have effective neighbourhood governance will empower ward councillors to take a greater leadership role in driving forward the priorities of their communities. This will help to move decision-making closer to residents, so decisions are made by people who understand local needs. Additionally, developing neighbourhood-based approaches will provide opportunities to organise public services to meet local needs better.” (from the explanatory notes, paragraph 98).

Assets of community value

The Localism Act 2011 introduced the “community right to bid” by way of the ”assets of community value” process (for a couple of examples of litigation in relation to assets of community value, see my 14 July 2018 blog post, 2 ACV Disputes). In that blog post I summarised the rather toothless nature of the current system as follows:

“The listing of land or buildings as an asset of community value has legal consequences but ones that will seldom be determinative as to an owner’s longterm plans. Whilst disposal of a freehold or long leasehold interest can’t take place without community groups being given an opportunity to bid, there is no obligation to accept any community bid that is made. The listing can be material in relation to the determination of an application for planning permission, but the weight to be attached to the ACV listing is a matter for the decision maker.”

The Bill proposes the strengthening of the system in several ways (again quoting from MHCLG’s guidance document):

- “The community group and asset owner will either negotiate a price for the asset, or an independent valuer will set a price based on the market value. Under Community Right to Buy, the moratorium on the sale of the asset will be extended to 12 months, giving community groups more time to raise funding to meet the agreed purchase price. Asset owners will be able to ask the local authority to check that community groups are making sufficient progress on the sale 6 months into the moratorium.

The definition of an ACV will also be expanded to help protect a wider range of assets, including those that support the economy of a community and those that were historically of importance to the community. Community groups will be able to appeal the local authority’s decision on whether an asset is of community value and local authorities will be supported to deliver the powers with new guidance.”

(This will raise significant concerns with land owners I feel sure).

- Although sports grounds can already fall within the ACV definition the Bill will introduce “a new type of ACV – the Sporting Asset of Community Value (SACV) and automatically designate all eligible sports grounds as such. As with the standard ACV regime, communities will have the first right of refusal when a ground is put up for sale. SACV status will also provide enhanced protections for sports grounds. For example, unlike the standard 5-year renewal period under the ACV system, sports grounds designated as SACV will retain this status indefinitely. Other facilities – such as car parks – that the ground depends on to function effectively – will also be eligible for SACV listing, preventing the ground from being undermined by the intentional removal of its supporting assets.”

Abolishing upwards only rent review provisions in commercial leases

This landlord and tenant law provision, well away from my wheelhouse, is a strange outlier within the Bill. As per the MHCLG guidance:

“The Bill will ban UORR clauses in new commercial leases in England and Wales. Commercial leases include sectors such as high street businesses, offices and manufacturing. Some very limited areas such as agricultural leases will be exempt. The ban will also apply to renewal leases where the tenant has security of tenure under Part II the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954. The ban aims to make commercial leasing fairer for tenants, ensure high street rents are set more efficiently, and stimulate economic growth.

Following the ban, if a UORR clause is in a new or renewal commercial lease, the requirement for rent not to decrease will be unenforceable; the new rent will be determined by whatever methodology is specified in the lease, for example in line with changes to the retail price index. The new rent may be higher, lower or the same as the previous rent.”

Enjoy your drink. Enough of all these acronyms, it’s an IPA for me please, thank you.

Simon Ricketts, 11 July 2025

Personal views, et cetera