We should be constantly pinching ourselves at the good fortune of (1) living in, what was to previous generations, the future, and (2) having been given the privilege and responsibility of in turn helping to shape a small part of the world in which future generations will live and work.

It wasn’t so long ago that the life of a planning lawyer used to entail posting out cheques for copies of local plans and decision notices (having first had various telephone conversations – yes telephone conversations – to work out the price) or, if it was a rush job, turning up at the local authority’s offices to go through the paper files, or (the horror) sit at their microfiche machine. And sometimes we actually had to sit in a library, with books.

The Planning Portal, individual local authority planning portals and the Planning Inspectorate’s Appeals Casework Portal have been a game changer – but we are on the cusp of bigger improvements in terms of efficiency, transparency of information and the potential for better informed public engagement.

Last week at Town Legal we co-hosted a breakfast roundtable discussion with Gordon Ingram and Claire Locke from Vu.City to discuss digital 3D planning but the discussion went wider to discuss where we are with digital planning data more widely as well as the Planning Inspectorate’s recent guidance as to the use of artificial intelligence. We had a range of participants from the private and public sectors but I was particularly grateful to Nikki Webber, digital planning lead at the City of London who subsequently shared some of the links to resources that I will now use in this post.

There has been discussion about digitising the planning system for so long that there’s a risk of taking it all for granted, or of not focusing on the vision and how achievable it now is. But huge advantages in terms of efficiency, transparency and quality of decision-making surely flow from (and indeed are already starting to flow from):

- Ensuring that data that enters the planning system is available for wider public use and that common standards are adopted wherever possible

- Using technology (1) to give decision-makers and the public a better understanding of the policy options before them and the ability to visualise development proposals in context and (2) to enable better and more straight-forward opportunities for the public to express their views, on the basis of a better understanding of the issues

As the old British Rail slogan went, we’re getting there.

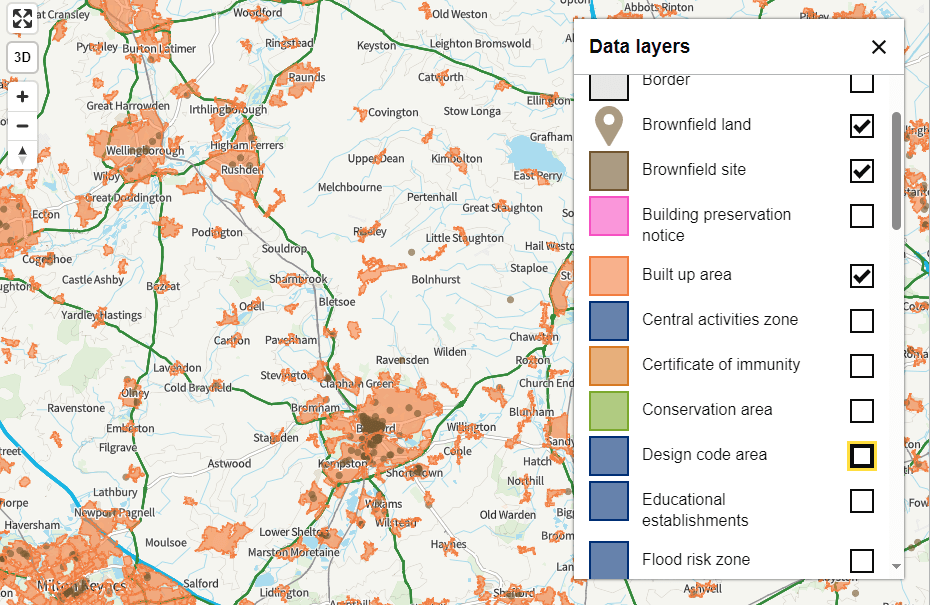

MHCLG’s Digital Planning Programme is doing great, practical, work. Its planning data platform is still at beta testing stage but is already useful, showing planning and housing information provided by local authorities on a single interactive map. It also announced on 18 October 2024 that it is now turning to developing data specifications for planning applications, looking into “where specifications are required, and define them clearly, taking into account how this data will be used by the planning community. This will build on the work that we have already started, such as the draft specifications for planning applications and decisions , and planning conditions .”

The legislation required to underpin these advances is taking shape. Part 3, chapter 1 of the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act 2023 deals with planning data. Sections 84, 85, 86 are already in force as of 31 March 2024, by virtue of the Levelling-up and Regeneration Act 2023 (Commencement No. 3 and Transitional and Savings Provision) Regulations 2024 .

Quoting in part from LURA’s explanatory notes:

Section 84 gives the Secretary of State and devolved administrations “the power to regulate the processing of planning data by planning authorities, to create binding “approved data standards” for that processing. It also provides planning authorities with the power to require planning data to be provided to them in accordance with the relevant approved data standards.”

“Example (1):

A planning authority creating their local plan: Currently planning authorities do not follow set standards in how they store or publish local plan information. Through these powers, contributions to the preparation of a local plan and the contents of a local plan will be required to be in accordance with approved data standards. This will render local plan information directly comparable, enabling cross-boundary matters to be dealt with more efficiently as well as the process of updating a local plan as planning authorities will benefit from having easily accessible standardised data.

Example (2):

Central government trying to identify all conservation areas nationally: In the existing system, planning authorities name their conservation areas using different terms (e.g., con area, cons area) making it hard for users of this data, such as central government to identify which areas are not suitable for development and what restrictions are in place. By setting a data standard which will govern the way in which planning authorities must name their conservation areas, and planning authorities publishing this machine-readable data, a national map of conservation areas can be developed which can be used to better safeguard areas of special importance.”

Section 85 allows planning authorities, by published notice, to require a person to provide them with planning data that complies with an approved data standard, that is applicable to that data.

Section 86 allows regulations to be made “requiring a relevant planning authority to make such of its planning data as is specified or described in the regulations available to the public under an approved open licence”.

Whilst these sections are already technically in force, they cannot fully take effect until the government determines what those specific approved data standards will be. Section 87 is also important but not yet in force, which gives the Secretary of State the power to approve software, that is in accordance with data standards, to be used by planning authorities in England. Clearly there is great advantage in consistency of approach as between public authorities as to the software used, so as to ease the user experience and presumably to make providers’ investment in technology more viable but this is to be balanced as against the risks arising from any particular provider being able to exploit a dominant position. Is not a private/public sector approach possibly the most appropriate, as per the Planning Portal (a joint venture between MHCLG and TerraQuest Solutions Limited)?

MHCLG’s Digital Planning Programme has also been funding local authorities’ digital planning projects and its website has links to various case studies. For instance, take a look at Southampton City Council’s work on increasing accessibility and understanding to improve public engagement, using a Vu.City developed 3D model to help local residents understand what proposals may look like in situ and potentially ease concerns about increased densities. How transformative it would be if local people could see the different options that here might be to accommodate local housing and employment development needs within an area. Or in terms of development management and transparent public engagement, look at London Borough of Camden’s beta testing as to the information it can provide as to major applications in its area (particularly look at the use of images of the proposal and at the “How could this affect you?” section).

With progress of course comes the need for caution. These tools need to be based on accurate information and the risks are accentuated where outputs are the result of modelling and extrapolation of data, rather than taking the form of simply making the raw data more easily available. Any inputs and algorithmic influences need to be capable of being tested. Technology is requiring us all to be additionally cautious in all that we do. In my world for instance, the Law Society has published some useful, detailed, advice as to Generative AI: the essentials to provide a “broad overview of both the opportunities and risks the legal profession should be aware of to make more informed decisions when deciding whether and how generative AI technologies might be used”. As a firm we now have a policy on the use of AI; no doubt yours does too.

Understanding of the issues has in some ways already moved on greatly since my 27 May 2023 blog post You Can Call Me AI but the risks have increased now that use of Chat GPT and its competitors has become more mainstream. AI is undoubtedly being used by some to generate text for objections to planning applications. I’ve had prospective clients who mention in passing that before asking me the particular question they have looked online and “even Chat GPT didn’t have the answer” (these things are just large language models folks! Would you rely on predictive text as anything more than an occasional short-cut? I don’t like to think about what it must be like to be a GP these days).

Until recently I hadn’t thought about the additional risks arising from generative AI, of false images and documents being relied upon as supposed evidence in planning appeals. So I was pleased to see the Planning Inspectorate’s guidance on Use of artificial intelligence in casework evidence (6 September 2024).

The guidance says:

“If you use AI to create or alter any part of your documents, information or data, you should tell us that you have done this when you provide the material to us. You should also tell us what systems or tools you have used, the source of the information that the AI system has based its content on, and what information or material the AI has been used to create or alter.

In addition, if you have used AI, you should do the following:

- Clearly label where you have used AI in the body of the content that AI has created or altered, and clearly state that AI has been used in that content in any references to it elsewhere in your documentation.

- Tell us whether any images or video of people, property, objects or places have been created or altered using AI.

- Tell us whether any images or video using AI has changed, augmented, or removed parts of the original image or video, and identify which parts of the image or video has been changed (such as adding or removing buildings or infrastructure within an image).

- Tell us the date that you used the AI.

- Declare your responsibility for the factual accuracy of the content.

- Declare your use of AI is responsible and lawful.

- Declare that you have appropriate permissions to disclose and share any personal information and that its use complies with data protection and copyright legislation. “

AI is defined in the document very loosely: “AI is technology that enables a computer or other machine to exhibit ‘intelligence’ normally associated with humans”.

If I can carp a little, whilst the thrust of the guidance and its intent is all good, are we really clear what is and isn’t AI? What about spell-check and other editing functions, what about the photo editing that goes on within any modern camera? Do you know whether the information you are relying upon has itself been prepared partly with the benefit of any AI tool however defined and if AI has been used on what basis are you confirming that “its use complies with data protection and copyright legislation” given the legal issues currently swirling around that subject as to the material upon which some of these AI models are being trained? Perhaps some examples would be helpful of the practical issues on which PINS is particularly focusing.

Tech isn’t my specialism. Planning and planning law probably isn’t a specialism of those actually developing the technical systems and protocols. But I think we need to make sure that we are all engaging as seamlessly as possible across those professional dividing lines, so that the opportunities to create a better, more efficient, more engaging, possibly even more exciting planning system are fully taken. These are the things that dreams are made of.

Simon Ricketts, 20 October 2024

Personal views, et cetera

Extract from MHCLG’s planning data map