Making the planning system work more effectively should not be party political. So it is at least a good start to see that conservative life peer Charles Banner KC’s Independent review into legal challenges against Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (28 October 2024), commissioned by the previous government, has now been published by the current government. There is nothing very radical in it but, when it comes to making the planning system and associated litigation process work better, surely so much comes down to a version of Sir Dave Brailsford’s theory of marginal gains (see for example the undoubted success which was Bridget Rosewell’s review of planning inquiry processes).

LCB (is that yet an acceptable acronym?) had been appointed alongside fellow barrister Nick Grant in March 2024 to “explore whether NSIPs are unduly held up by inappropriate legal challenges, and if so what are the main reasons and how the problem can be effectively resolved, whilst guaranteeing the constitutional right to access of justice and meeting the UK’s international obligations.”

As per the Government’s press statement that accompanies the review, the Ministry of Justice has now separately published a call for evidence, based on his recommendations, ending on 30 December 2024 – “the Government is of the view that further analysis of a broader evidence base is necessary before decisions can be taken on the Review’s recommendations”.

Charlie Banner and Nick Grant had clearly put in the hours. It’s a well-thought through document. The review contains much useful background as to the current position, including analysis of the 34 challenges to DCOs which have been brought (30 of which have challenged the grant of a DCO and of which 4 claims were successful), average timescales for each stage of the process and some of the wider implications arising. This is valuable work – I’ve grumbled previously as to how unnecessarily difficult it can be to extract data like this.

They interviewed over 60 people with experience in the field (I’ll declare an interest as being one of many spoken to. I’m feeling rather guilty now for the whole hour that I took up…).

Ten recommendations are made, which I summarise as follows, adding anything particularly interesting from the Government’s accompanying call for evidence as I go:

Recommendation 1 – For so long as the UK remains a member of the Aarhus Convention, there is no case for amending the rules in relation to cost caps in order to reduce the number of challenges to NSIP.

Views not sought on this option. The call for evidence notes the government’s separate call for evidence seeking views on options to bring the UK’s policies into compliance with its obligation under the access to justice provision of the Aarhus Convention (30 September 2024)

Recommendation 2 – There is no convincing case for amending the rules in relation to standing to reduce the number of challenges to NSIPs.

Views not sought on this option.

Recommendation 3 – The current three bites of the cherry to obtain permission to apply for judicial review is excessive and should be reduced to either two or one: (1) an oral hearing in the High Court with a target timescale of within four weeks of the deadline for filing of acknowledgements of service and (2) consideration on the papers in the Court of Appeal within four weeks of the application for permission to appeal against the refusal of permission to apply for judicial review.

The commentary in the call for evidence document is interesting, pointing at the potential for any such changes to apply to judicial reviews of other planning decisions:

“If the proposed change could result in time and cost savings for litigants and the courts, whilst maintaining adequate access to justice, there could be merit in considering this change not only in the context of NSIPs but also for judicial reviews of other planning decisions in general.

The Government is, however, of the view that more evidence is required to inform a decision on the implementation of this proposed change. We would, therefore, welcome views on the expected benefits and potential risks of this change, both in the context of the NSIP regime and in wider judicial review cases.”

Recommendation 4 – There may be a case for raising the permission threshold for judicial review claims challenging DCOs, which could be achieved by amendments to the CPR.

“The Government is of the view that in addition to the practical risks highlighted in the report, there is a more fundamental concern that raising the permission threshold in this way could unduly restrict the right of access to justice…the Government would however welcome views with supporting evidence, where available, on the likely benefits and potential risks of raising the permission threshold as discussed in the report.”

Recommendation 5 – On balance the case has not yet made out for a panel of judges with specialist NSIP experience to be eligible to hear judicial review challenges to DCO decisions.

The call for evidence document notes that there are currently 35 full time High Court judges authorised to consider planning cases, four of whom specialised in planning as practitioners prior to joining the judiciary.

“The Government would welcome views on whether this idea should be taken forward, whilst recognising that the authorisation of judges to hear certain types of case is part of judicial allocation and deployment which is a matter for the judiciary. We would particularly welcome views from members of the judiciary.”

Recommendation 6 – The Civil Procedure Rules should provide that DCO judicial reviews are automatically deemed Significant Planning Court Claims.

(This is important because stricter target timescales apply. All DCO judicial reviews to date have been treated as such – so this should not be controversial…).

“Given the national significance of NSIPs and the complexity of the claims against them, there is a case for formalising the existing practice of designating all judicial review cases concerning DCO decisions as Significant Planning Court Claims. The Government would, however, welcome views on the practical benefits of formalising this existing practice.”

Recommendation 7 – Automatic pre-permission case management conferences should be introduced in relation to judicial review claims challenging DCOs.

Views sought.

Recommendation 8 – Target timescales should be set for the Court of Appeal to target timescales for determine applications for permission to appeal, and (where permission is granted) thereafter substantive appeals.

“The Government considers that a better understanding of the causes of the current delays at the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court is needed to determine whether imposing target timescales would help to ensure consistent timely processing of DCO judicial reviews at the appellate courts. In addition, although the report suggests that the relatively limited number of DCO judicial review claims means that these timescales should not be too onerous on the courts, we would welcome views, particularly from the senior judiciary, as to how the introduction of target timescales might affect the operation of the appellate courts.”

(NB somewhat deferential? There are undoubtedly delays at the appeal stages. delays which look to mere mortals to be capable of reduction…)

Recommendation 9 – The President of the Supreme Court should be invited to consider amending the Supreme Court Rules to introduce target timescales for the determination of applications to the Supreme Court for permission to appeal in judicial review challenges to DCOs.

Same commentary as for recommendation 8.

Recommendation 10 – The Planning Court and Court of Appeal should be invited to publish data on a 3 month rolling basis which, at minimum, should indicate the number and percentage of cases which in the last 3 month period have met the target timescales either for NSIP cases specifically or Significant Planning Court cases generally, or both; as well as what the average and maximum turnaround times have been in that period (for both the permission and the substantive stages).

“This recommendation to invite the Planning Court and the Court of Appeal to improve the way they publish data on the progress of DCO judicial reviews and/or planning cases would not directly address the issue of delays, but it could, as the report notes, provide stakeholders with greater transparency and help inform consideration of further procedural reforms. The report also suggests that this could be easily implemented at little or no additional cost. The Government would welcome views on the likely benefits and potential costs of this proposal.”

The Government is also welcoming views as to:

- The review and its methodology more generally and whether there is indeed a case for streamlining the process for judicial reviews of DCO decisions

- other possible changes that could help reduce judicial review related delays to the delivery of NSIPs and provide parties greater certainty in the process. Any proposed change must, however, ensure the right of access to justice is maintained in line with the UK’s domestic and international legal obligations.

Simon Ricketts, 28 October 2024

Personal views, et cetera

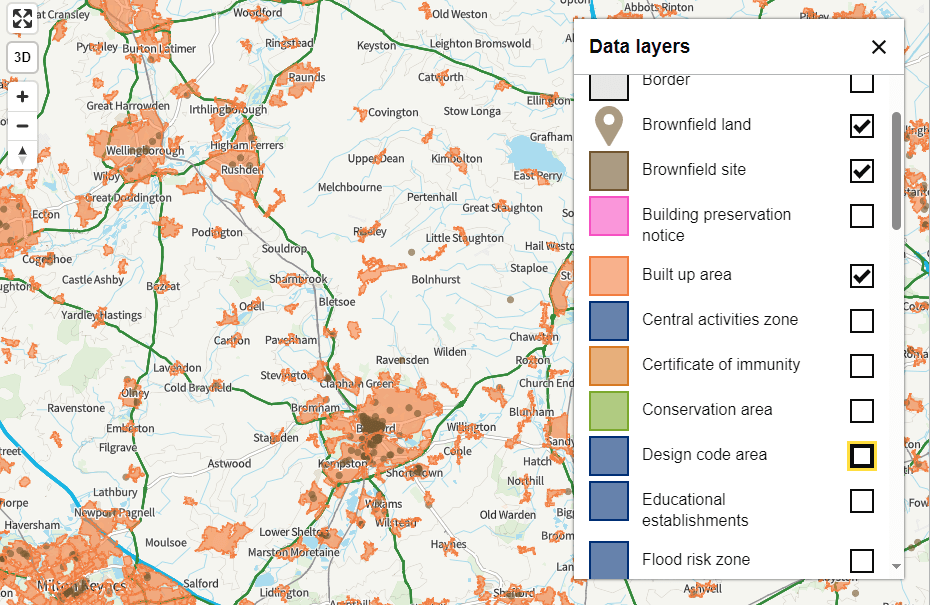

Table from review